Veterans’ perspectives, and the great task remaining

08 March 2019 – Jessica L. Adler

projects, veterans, methods, NEH, memory, collaboration, museums, education, government, oral history

The Dialogues on the Experience of War program is sponsored by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Education Division

Army nurse Norma J. Griffiths-Boris returned from Vietnam not just with haunting memories of unpreventable death—smells of burned flesh, sights of traumatic head wounds—but also with a powerful impression of her non-traditional work environment. At war, she and fellow nurses held positions of authority. Back in the United States, they were considered subordinate to medical students. “My anger,” Griffiths-Boris said, “began to seethe.”

It did not help that her marriage was falling apart and she had medical problems: gastric pain, an irregular heartbeat, and depression. “I had been on almost every psychotropic medication,” she told a congressional committee in 1983, “and still could not enjoy, share, love, and sometimes work.”

Griffiths-Boris’ testimony was the subject of a recent conversation at the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Miami Vet Center, where former service members from diverse backgrounds, ranging in age from 38 to 78 years old, met to reflect on the history of veterans’ experiences as part of a National Endowment for the Humanities’ Dialogues on the Experience of War program overseen by the Florida International University department of history and supported by the Florida State University Institute for World War II and the Human Experience, the Combat Hippies, and the Wolfsonian-FIU Museum.

“Of all the readings, I learned the most from this one,” said a veteran who had served in Cambodia during the Vietnam War. He looked around the room, where a few of the ten group participants were women. “What you women have been through . . . ,” he said, shaking his head.

His revelation was telling; there is no singular veteran perspective. That was a point that arose multiple times during our four weekly gatherings, as we reflected on artwork and readings related to veterans’ experiences during and after World War I, World War II, the Vietnam War, and post-9/11 conflicts. At a moment when so much divides us, a small veterans’ discussion group served as a model for how people with very little in common could come together to talk history and consider and respect the plurality of the human experience—at war and beyond.

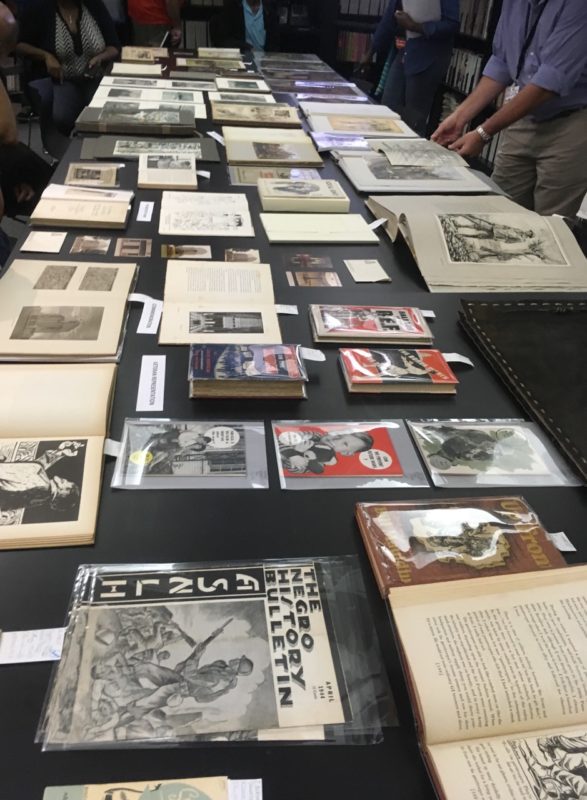

A couple of weeks before discussing Griffiths-Boris’ testimony, we had taken a bus to the Wolfsonian-FIU Museum, where we viewed paintings, propaganda, and other materials from the World War I era.

The group visited the galleries and library of the Wolfsonian-FIU Museum, where they viewed artwork, propaganda, and other visual arts related to World War I and World War II. Photo credit: Wolfsonian-FIU Museum

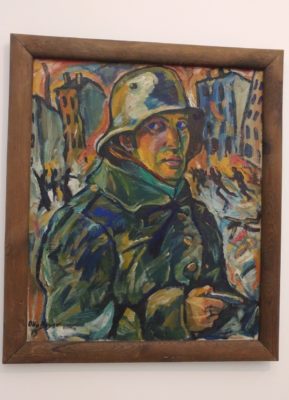

“Revolution” by Otto Beyer. Photo credit: Wofsonian-FIU Museum

In an airy exhibit space, we gathered around Otto Beyer’s 1919 painting, Revolution, which features a soldier standing in the foreground, his eyes cast sideways, his expression worried and forlorn as a scene of chaos unfolds in the street behind him. One veteran looked at the piece and saw the soldier as a protector, guarding the viewer from the mayhem of the wider world. Another saw an overwhelmed and pained man searching for a way out. Those of us who had never served in the military initially focused on something much less personal: how the painting related to historical accounts of the violence and turmoil of post-war Europe.

At the Vet Center the following week, we talked about personal accounts of men and women who had served during World War II. Older Black veterans identified with the autobiography of Margaritte Ivory-Bertram, an African American woman who served as a nurse during World War II. Ivory-Bertram wrote with eloquent frankness about a white colleague who refused to work as her subordinate, even as forty-six severely wounded soldiers arrived at the hospital in need of attention.

“I had no time to stop and talk to her,” Ivory-Bertram recalled. “These men were my responsibility and I intended to give them the best possible care.”

The week we read Griffiths-Boris’ testimony, our focus was on the Vietnam War and its aftermath. We were moved by a 2017 oral history with former Senator and triple amputee Max Cleland, who, as the head of the Veterans Administration in the late 1970s, helped to establish access to outpatient counseling centers like the one where we were meeting.

“49 years later, it burns the hell out of me to know . . . what was very tough to admit early on . . . that Vietnam was a complete . . . disaster,” Cleland said. “To know that it’s one of the great military failures in the world and to have been part of it, intimately a part of it, is a terrifying thing . . . and to have paid such a price: losing my two legs, my right arm . . . that’s a hell of a price to pay for anything, much less Vietnam.”

One fellow Vietnam veteran in the room noted that he and others held different beliefs about the war; he was proud to have served in a conflict that he firmly believed helped to stop the spread of communism. Despite his own convictions, he revered Cleland and valued his perspective.

During our final week together, we hearkened back—way back—to 1863 and Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered after a deadly Civil War battle, to ponder why the speech became such a monument in American history.

“It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us,” Lincoln said. “. . . We here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom. . .”

One participant—a devout Christian—was moved by the centrality of God in the president’s conception of nationhood. Another interpreted the speech as a proud declaration that the United States is exceptional and worth defending. A third pointed out that Lincoln’s words could have served to rile up young potential recruits, while another was uncomfortable with the idea that they could be construed as a glorification of war.

Our varied interpretations of the Gettysburg Address and other materials produced no consensus. If anything, they highlighted our widely varying perspectives. But everyone in the group shared one thing in common: we were willing to try to understand—and relate to—the feelings of pain and pride conveyed by each other and by counterparts from other generations.

These days that endeavor may be one of the greatest tasks remaining.

~ Jessica L. Adler, Ph.D. is an assistant professor with co-appointments in the department of history and the department of health policy & management at Florida International University.