Evaluating the Guantánamo Public Memory Project

21 February 2014 – Michael Jordan

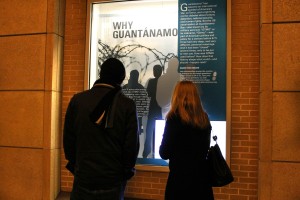

GPMP exhibit on display at NYU’s Kimmel Windows Gallery, December 2012 Photo credit: Picture Projects

Editor’s Note: This piece continues a series of posts related to the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, a collaboration of public history programs across the country to raise awareness of the long history of the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) and foster dialogue on its future. For an introduction to the series, please see this piece by the Project’s director, Liz Ševčenko.

In her piece introducing the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, Liz Ševčenko notes, “Faced with the challenge of combating apathy and amnesia, the Project took a gamble: give the most responsibility to the people who know the least, and invite them to build their own understanding along with the rest of the world’s.” As one of the student curators invited to participate in the Project’s creation, I was left wondering, “Did the gamble pay off?”

My personal experience with the Project has been transformative. Throughout my undergraduate and graduate studies, Latin American history, and specifically US and Latin American relations historically, has been a keen interest of mine. I remember my astonishment upon learning about the US’s history of military intervention, economic dominance, covert operations, and support of dictators and paramilitaries throughout the region. Through readings, lectures, and classroom discussions I wanted to understand as many perspectives as possible of this contested history. Yet, while the classroom provides an important, comfortable space for discussing polemic issues, I have found that this dialogue often remains within those walls and seldom prepares students to engage others about such issues in the public arena.

I was intrigued by the Guantánamo Public Memory Project because it not only took this conversation to the public outside of the “ivory tower” but also departed from a traditional expert-learner approach to curation. Instead of teaching, it offered dialogue—a dialogue based on learning about GTMO’s history, placing “expert” and “learner” at the same table. As the Brazilian scholar Paolo Freire observed, such practice creates “teacher-students” and “student-teachers” whereby both learn from one another, each offering their experience and perspective (Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed).

To explore the Project’s reception and effectiveness at stimulating dialogue, I continued my participation as an intern, designing anonymous surveys for student-curators and visitors, which I would ultimately use to write my MA thesis. In its funding application for the Institute of Museum and Library Studies, the Project listed its main desired outcomes as increased knowledge of GTMO’s history; increased awareness of GTMO’s significance in the world, the US, and for human rights; greater empathy for the diversity of lives lived and touched by GTMO; and an increased ability to engage in debate and decisions about GTMO’s future and related issues. If successful, such a model of horizontal curation—working with community populations like students—and emphasis on public dialogue would merit consideration for public institutions grappling with contested histories more generally.

Yet, to assess “knowledge,” “awareness,” “empathy,” and “likelihood to engage in public dialogue,” picking a number on a scale of 1-10 to answer a question such as “How much do you feel you learned?” seemed too simple. A series of numbers might reveal a pattern, but alone they do not convey the texture of that pattern and the distinct thoughts behind the pattern. For this reason, I chose to use a combination of quantitative and qualitative questions. For instance, to gauge empathy, I asked if visitors felt that the issues raised in the exhibition were important to them and/or their community, highlighting to what degree visitors personally identified with larger, national issues. I also coded responses to other survey questions, such as information recalled and what issues visitors wished to discuss. This approach highlighted the frequency with which issues related to individual human experiences on the base emerged relative to other historical information.

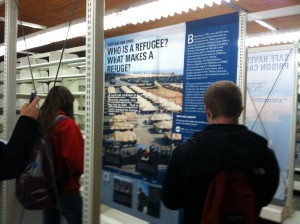

GPMP exhibit at Rutgers University Douglass Library, Feb 18 – March 29, 2013 Photo credit: Michael Jordan

Drawing on responses from the student-curator survey online and paper surveys from exhibition venues thus far, I came to an important but perhaps obvious conclusion. Increasing the level of participation in the exhibition yields greater increases in subject knowledge, awareness, empathy, and likelihood of engaging in dialogue. This was perhaps best demonstrated through a comparison of the online student survey with visitor survey samples from New York University (NYU) and Rutgers. Indeed, those most likely to carry the dialogue forward were the students who were given the greatest amount of creative control in the exhibition and who felt that their contribution was significant. In addition, the second most likely population to discuss issues raised in the exhibition with others came from Rutgers, where visitors participated in a tour and facilitated dialogue of GTMO’s history in one of the university’s libraries.

These results might be compared with the lowest likelihood of discussing GTMO with others from respondents at NYU. Here, the exhibition faced an open street near Washington Square Park in New York City with no additional programming. Certainly a benefit of the NYU venue was that any passersby who might not otherwise see the exhibition were able to stop and read. This contrasted with the exhibit’s other placement in a library at Rutgers. But ultimately this limited participation did not foster the same increase in knowledge, awareness, empathy, and likelihood of engaging others in dialogue.

The survey results collected thus far indicate that similar future projects would benefit from incorporating community populations into the curatorial process and from incorporating a variety of platforms for visitor engagement. Through horizontal curation and engagement, institutions grappling with contested histories may not only generate more dialogue but also greater investment in that dialogue as one’s degree of participation increases.

~ Michael Jordan received his Masters in Latin American and Caribbean Studies from New York University this past fall. As an intern with the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, Michael led Project Evaluation from January 2013 until December 2013. Prior to studying at NYU, Michael received his BA in History and Spanish from the University of Virginia.