Feminism unfinished: Finding work-life balance as public history parents

09 June 2020 – Andrea Ringer and Brandi Burns

parenting, careers, pandemic, gender, covid-19, public history parents, working group, 2020 annual meeting, feminism, work-life balance

“Public History Parents: Leaning In, Opting Out, and Finding a Work-Life Balance” is a working group created in conjunction with the 2020 National Council on Public History (NCPH) annual meeting. It formed to address the unique needs of parents in the public history field. Group facilitators Nicole Hill, Emily McEwen, Sue Nguyen, Erin Gregory, and Ellen Rankin joined discussants who described themselves as independent contractors, academics, city historians, and museum professionals. Each of the eleven group members joined under the common experiences surrounding parenthood and used these experiences to discuss parenting among public historians.

The Public History Parents Working Group centered their discussion on these five questions. Screenshot credit: Public History Parents Working Group, NCPH, 2020

Whose Problem is Parenting?

Gender Equity in Museums Movement published a paper in March 2019 in which they predict that, based on current trends, 70 percent of the museum field will be women within the next decade. As they observe, “female-dominated professions carry with them the economic and social burdens of ‘women’s work.’”[1] The composition of our working group reflected this, as none of our group facilitators identified as cisgender male. We wondered if it was a coincidence or if it exemplified a broader trend that balancing career and parenthood is viewed as a problem only for some, and not all. Is the balancing act based on societal mores or self-inflicted insecurities? From our experience, it seems that the balancing act is based on societal mores and inequalities created by social structures. Those social structures are reinforced in “pink-collar” fields, fields where women are the predominant gender of the workforce. The devaluing of labor from women leads to what members of our working group—and many others—experience: the social structures that lead workers to attribute their feelings around balancing career and parenthood as a self-inflicted insecurity. In reality, we are all experiencing the legacy of unfinished feminism, the rights for which feminists continue to advocate. In Feminism Unfinished: A Short, Surprising History of American Women’s Movements (2014), we found a compelling history of the women’s movement and its effect on the world we public history parents work in today. The authors of the book present a concise history of the feminism movement that provides a useful lens through which we could explore current workplace practices and experiences.

Feminism’s Role in Shaping Our Workplaces

When we (Andrea, Brandi, and participants in the working group) initially proposed the topic of how the history of feminism shaped our working reality as public history parents, COVID-19 was not raging around the planet, shifting the way all people have had to adjust their working and parental duties. Yet, as the workplaces of each working group contributor closed in the weeks leading up to the NCPH meeting, our topic became even more pressing.

Attributes that came up for us Public History Parents often focused on flexibility. Our case statement says, “Self-employed public historians must often rely on unconventional childcare accommodations, as do many working in the public history field. It can be difficult to find reliable childcare after 6 pm and on weekends.” In our virtual meeting, as we expounded on these statements it became clear that no matter the place of employment—from the U.S. to Canada and from government employers to self-employed historians—systemic barriers create difficult, and often unacknowledged, challenges for working parents. These challenges include: working odd hours in the evening and weekends for public programming; organizations’ relying on contractors instead of hiring full-time staff; high-turnover as employees try to find permanent employment in the field; and the prevalence of burnout as people at all levels of the field try to keep up amongst the constraints of being perpetually understaffed and underfunded.

Those parents in other fields who have not lost their jobs are experiencing the benefits of flexibility right now, while also confronting the lack of external childcare in order to give themselves some quiet time to work. In many ways, the perks and issues of flexible schedules are demanding the most attention from working parents in this pandemic, while piecemeal paid family-leave solutions are entering national conversations. But these issues are far from new. Creating equitable policies for parents, particularly mothers, has been a driving force of the women’s movement over the last one hundred years.

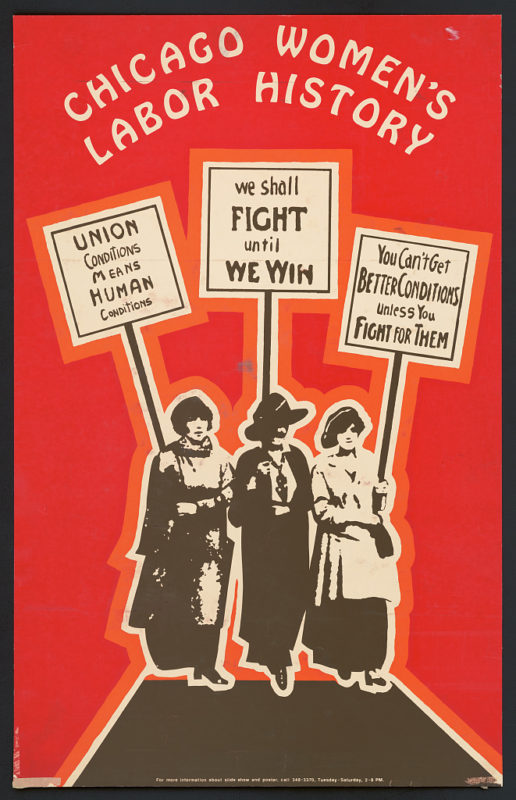

The slogans “Fight Until We Win” and “You Can’t Get Better Conditions Unless You Fight For Them” reflect the perseverance women’s rights activists have demonstrated to make changes in our current working environments. Photo credit: Library of Congress

In Feminism Unfinished, historians Dorothy Sue Cobble, Linda Gordon, and Astrid Henry trace a 100-year history of the women’s movement, beginning with the women’s suffrage amendment in 1920. They demonstrate that childcare has always been central to feminism. For example, early social justice feminists pushed workplace policies that acknowledged women’s needs. The movement in the 1960s included a constant push for government-subsidized childcare, which had dissipated after World War II. The movement headed by Generation X and Millennials pushes against a superwoman ideal and focuses on the need for a healthy work-life balance. The search for this balance is caused by the issues ubiquitous in our workplaces across the sector. As Astrid Henry notes in Feminism Unfinished, American workplaces still adhere to the notion of a “mythical male worker,” who has unlimited hours to devote to paid labor, which compounds unpaid work, like childcare, that is often undertaken by women.[2] What we have found, and what many others can attest to, is that the mythical male worker and the superwoman ideal are alive and well in how the history field functions. One of the authors’ key conclusions is that “Feminism is far from over. We don’t know what it will look like, because each generation will reinvent it.”[3] After mass social distancing and shelter-in-place orders across the globe have subsided, we may very well see a new wave of feminism, a feminism that is reinvented by our generation because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Childcare will certainly be a top concern; with parents worldwide juggling roles as employees, caregivers, and schoolteachers to their children, post-2020 feminism will reinforce the fundamentals of the movement—caregiving and cooperation.[4]

Where We Go From Here

In the spirit of cooperation, the working group will create documents for public history parents to use while advocating for themselves in the workplace, whatever that will look like after COVID-19. These editable documents will help individuals professionally and effectively advocate for themselves during pre-parental and early parental stages. Issues like fertility treatments, lactation support, and human resources processes will be addressed. Ideally, these forms will be amended over the years with feedback from other public history parents and will improve NPCH’s ability to support members, and their families, throughout the various stages of their careers.

~ Andrea Ringer is an assistant professor at Tennessee State University.

~ Brandi Burns manages history programs for the City of Boise’s Department of Arts & History.

[1] Gender Equity in Museums Movement, “Museums as a Pink-Collar Profession: The Consequences and How to Address Them,” Gender Equity in Museums Movement, 1.

[2] Dorothy Sue Cobble, Linda Gordon, and Astrid Henry, Feminism Unfinished: A Short, Surprising History of American Women’s Movements (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2014), 193.

[3] Cobble, Feminism Unfinished, 230.

[4] Cobble, Feminism Unfinished, 230.