Recent trends in the field: Summarizing the findings of the Joint Task Force on Public History Education and Employment

08 September 2020 – Daniel Vivian

Editors’ Note: This is the first of five posts summarizing the findings of the Joint Task Force on Public History Education and Employment, an initiative launched in 2014 to study trends in public history education and employment.

How did the 2008 financial crisis affect public history employment? How did public historians fare in its aftermath, and how has the field changed since? As we grapple with the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, data compiled by the Joint Task Force on Public History Education and Employment offers insight into how public historians weathered the global crisis of a decade ago and some of the directions in which the field may be headed.

Profile of Employer Survey Respondents.

The task force, formed in 2014, is a collaborative effort of the American Association for State and Local History (AASLH), the American Historical Association (AHA), the National Council on Public History (NCPH), and the Organization of American Historians (OAH). During the past six years, the task force has collected extensive data on public history education and employment in an effort to understand broad trends in the field. The task force grew out of concerns that became widespread among public history educators and practitioners during the Great Recession. As NCPH President Robert Weyeneth observed in 2013, a “perfect storm” of circumstances seemed to suggest grim prospects. The weak economic recovery had kept job opportunities limited, and cuts to federal and state budgets had eliminated many public history positions. At the same time, public history programs had multiplied at a brisk pace for more than a decade. Colleges and universities had eagerly launched new programs, seemingly oblivious to the state of the job market and the challenges facing the field. Some of the new programs seemed under-resourced, ill-prepared to provide the training and experience needed to prepare graduates for successful careers. Further, growing numbers of public historians, many of them graduates of new programs, seemed to be entering the job market at a time when job opportunities had become scarce. In all, multiple developments seemed to portend years of difficulty if not severe distress.[1]

Weyeneth also observed that the notion of a “perfect storm” derived mainly from anecdotal information. The implications of some anecdotes seemed plainly apparent, but others seemed to differ from the experiences of some public history program directors. Seeking to reconcile the disparate streams of information, Weyeneth emphasized the need for “hard data.” Specifically, he urged that NCPH collect data about job placement rates and trends in employment and education.

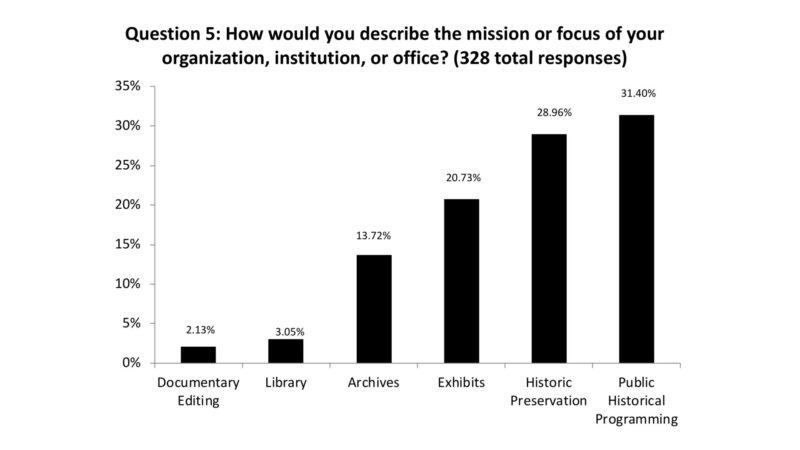

The task force responded to Weyeneth’s charge by launching a survey of public history employers. Released in fall 2015, the survey sought to answer a question public history educators and practitioners had raised as the number of public history programs had grown: was graduate education providing students with in-demand skills and knowledge, or did a disconnect exist? The survey consisted of eighteen multiple-choice questions and invited respondents to submit written comments. Promoted through blog posts, social media and conference announcements, the survey received 401 responses from a broad cross-section of employers, including museums, historical societies, archives, and historic preservation organizations, as illustrated in the bar graph above.[2]

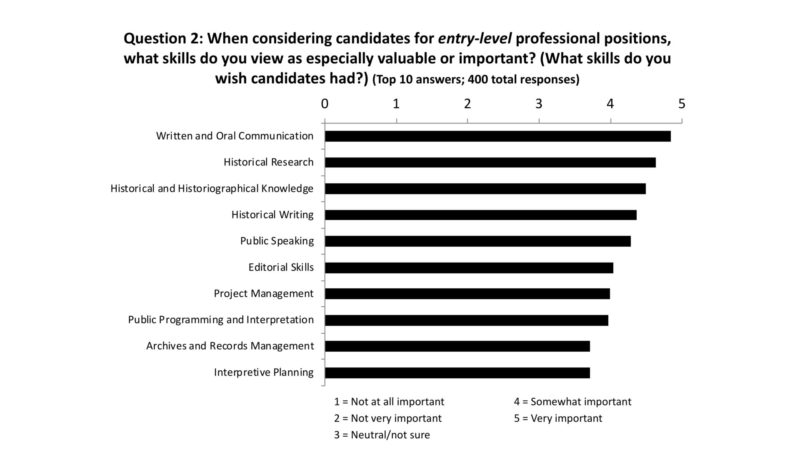

Survey respondents emphasized the importance of traditional historical skills and knowledge while stressing the value of expertise in project management, fundraising, and digital media development. For entry-level professional positions, respondents named writing and public speaking skills, historical and historiographical knowledge, and experience developing interpretive programs as crucial. Editorial skills, archives and records management, and interpretive planning also ranked high among respondents’ priorities.

Skills for Entry-Level Professional Positions.

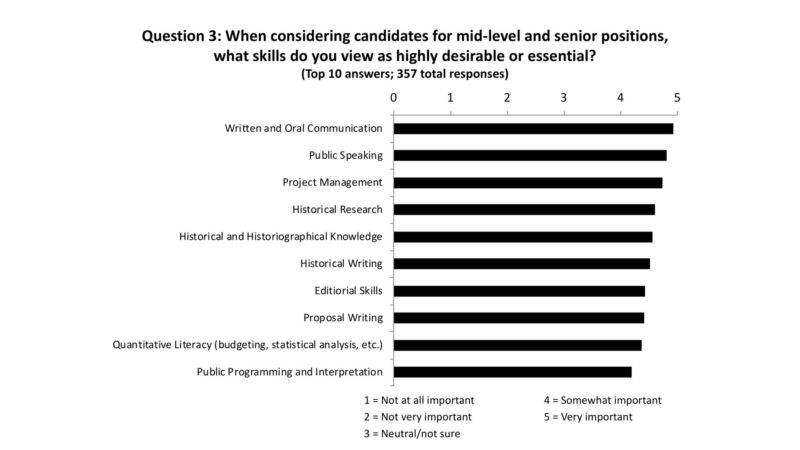

Expectations differed somewhat for mid-career and senior positions. Respondents again emphasized the value of historical skills but identified written and oral communication, public speaking, and project management as important. Proposal writing and quantitative literacy also ranked higher than they did in the responses for entry-level professional positions.

Top ten skills for mid-level and senior positions.

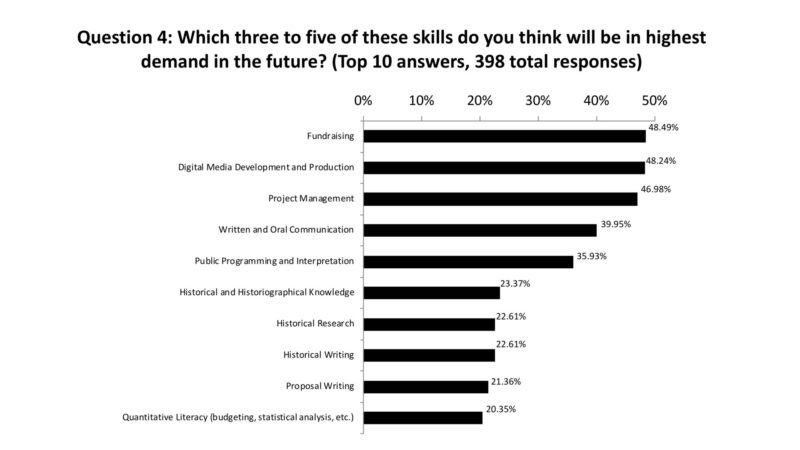

When asked to look to the future, respondents named fundraising, digital medial development, project management, and public programming as increasingly important areas of expertise. A second tier of responses included historical and historiographical knowledge, public speaking, historical research, proposal writing, and quantitative literacy. Overall, the survey indicates that strong historical training will remain fundamental to public historians’ labor but that technological innovations, changing funding models, and reliance on outside consultants will increase demand for other skills.

Skills that public history employers believe will be in demand in the future.

The written comments submitted by respondents concern a wide range of topics, with most focused on the general state of the field and working conditions in historical institutions. Overall, they provide a mixed portrait of public history employment. On the one hand, some respondents expressed enthusiasm for their work and identified themselves as fortunate to have found success in a challenging field. Some credited their graduate programs with providing excellent preparation for their careers, and some described experiences such as internships or early-career positions that provided springboards to later success. Others described frustrations associated with heavy responsibilities and long working hours while acknowledging that a love of history and convictions about the importance of their labor kept them motivated.

Other respondents provided less favorable perspectives. Many noted that declining public support for historical programs and growing competition for funding from philanthropic organizations have adversely affected historical organizations and made the work of public historians more challenging. A number of respondents observed that every public history job advertised receives strong interest from a large number of qualified applicants. Others identified low wages and limited opportunities for advancement as common. A few respondents urged students considering careers in public history to learn about the challenges they would face and the meager salaries typical of the field before committing themselves to a graduate program. Still others noted that the growing conservatism of American society and strong currents of anti-intellectualism has made it difficult for their institutions to address controversial topics and has eroded interest in history in general.

Based on the data collected, the task force concluded that the 2008 financial collapse had not caused a crisis in public history employment but severely affected historical organizations and institutions. Many professionals and recent graduates had struggled to find stable employment for several years after 2008. Further, the recovery had been slow and uneven, with some areas of practice worse off than others and significant variations in the job market based on geography and local conditions.[3]

The task force released a report on the employer survey, “What Do Public History Employers Want?” in 2017. The task force considers this report essential reading for graduate students and public history educators. It offers a road map for educating public historians and has not been rendered any less valuable by the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey questionnaire and compiled survey data are attached to the report as appendices. The comments submitted by respondents are available as a separate document.

The next post in this series will examine the task force’s second major project, a survey of public history careers. The third and fourth posts discuss some of the assumptions behind the “perfect storm” scenario and why the task force believes they missed important developments related to the shifting aims of public history education and the state of the job market. The fifth and final post considers a topic that the task force did not seek to explore but received extensive commentary from survey respondents and is on everyone’s minds: diversity and inclusion.

~Daniel Vivian is an associate professor and chair of the Department of Historic Preservation at the University of Kentucky. He has served as co-chair of the Joint Task Force on Public History Education and Employment since 2014.

[1] The task force did not study the public history job market. The insights expressed in this paragraph are based on comments provided by survey respondents and the collective knowledge and experience of the task force.

[2] NCPH staff created the survey in Survey Monkey, the online survey service (www.SurveyMonkey.com), based on instructions provided by the task force. The task force then made the survey available through the NCPH Survey Monkey account using a unique URL.

[3] Public History News 33, no. 4 (September 2013): 1, 4-8. The essay also appeared as a four-part series on History@Work.