History and tradition: Genealogical practice before 1700

07 August 2015 – Sara Trevisan

Editor’s note: In “On Genealogy,” a revision of the plenary address delivered in October 2014 at the International Federation for Public History’s conference in Amsterdam, Jerome de Groot argues that widespread popular interest in genealogy, and the availability of massive amounts of information online, challenge established historiography and public history practice. He invites other public historians to contribute to a debate about how we might “investigate, theorize, and interrogate” the implications of this explosion of interest in genealogy. We invited four scholars to contribute to this discussion. Sara Trevisan is the first of these scholars. Please consider adding your own comments to the conversation below.

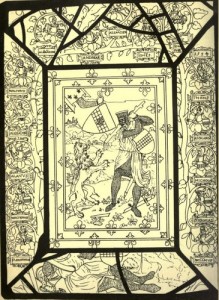

The Steward Window (1574), showing Banquo as the root of the family tree. Image credit: J.H. Round, Studies in Peerage and Family History (New York: Longmans: 1901)

In today’s genealogical search, lack of evidence on a family ancestor signifies the impossibility to assess any further their role within the structure of our genealogical tree. Genealogy is to us”‘a gesture to completeness that is continually thwarted by the limitations of the archive,” and thus shows us that knowledge can have an end.1 The search for family origins is therefore destined to remain ever unfulfilled and frustrated due to the epistemology of ‘historical truth” by which it is ultimately guided. Yet, until the second part of the seventeenth century–when the principles of historical method still had not fully taken hold–the “mythical” aspect of family origins was an integral part of genealogical reconstruction. This was especially true for monarchs and noble families.

Thanks to its linear diagrammatic form, genealogy was the perfect medium to state, rather than demonstrate, the prestigious origins of a family line, hence its legitimacy.2 We see this principle at work in a genealogy of the family of the Stewards (earlier “Stywards”) of Ely–no kin to the royal Stuarts–compiled in a manuscript dating from the late sixteenth century.3 The genealogy shows that Robert “Steward” of Ely (d. 1570) was a descendant of Banquo,4 ultimate ancestor to King James VI of Scotland and still remembered for his role in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Although the Stewards of Ely had put forward their descent from Banquo as early as 1549,5 it was only in 1575 that the claim received official recognition during the Herald’s “visitation” in Cambridgeshire.6 The Stewards of Ely’s genealogical statement was accompanied by a change in the family’s heraldry, as this only could publicly confirm their official descent from Banquo, hence their affiliation to the royal Stuarts. Their claim–scholars have found–was based on a forged Anglo-Norman charter allegedly issued by King Charles VI and on a fabricated record said to have been styled in 1520 by Sir Thomas Wriothesley, officer of the College of Arms.7 The genealogy and royal heraldry were nevertheless made official.8

The Stewards of Ely’s manuscript genealogy shows the family’s willingness to partake of the prestige of the royal Stuarts through the descent from a common ancestor (see image).9 The Latin title of the genealogy tells us that Banquo “lived around the year of our Lord one thousand,” and the genealogical table specifies that he died in 1048 at age 50.10 Yet, the same genealogical table is glossed as follows: “Concerning the origins of Banquo and of his previous lineage there is no certain evidence; [from his death] to the death of Robert Steward of Ely ran five hundred and seventy two years.”11 The lack of evidence was clearly not a problem for the compiler of the genealogy, nor was there any apparent effort further to investigate family history. As compared to today’s genealogical practice, the process is reversed: the Stewards of Ely must be shown to descend from Banquo, even though they are not; how can this goal be achieved?

In the medieval and early modern period, diagrammatic illustrations of family lines paid particular attention to a predetermined “long-term history,” a continuity between past and present that often required adjusting documentary evidence in order to maintain its fluency.12 Genealogy was used to communicate political and symbolic messages, and ideological continuity rather than “historical truth” was its main aim. Indeed, at least until the early seventeenth century, genealogies were generally based on a “tradition” that was closer to the workings of oral rather than written history. This history could be found in genealogies and chronicles based, in turn, on vague, allegedly lost (if not fabricated) sources, usually aiming to conceal their ultimate nature of oral accounts.

At the time when the Stewards of Ely’s genealogy was officialised, the key source for Banquo’s story was Hector Boece’s Scotorum Historiae (1527). Boece’s work was the first chronicle ever to mention Banquo in a history of Scotland, whose source, we are told, was an account now lost. Banquo is presented as an accomplice to Macbeth. However, in order to stop Banquo’s future line of kings as prophesied by the three Witches, Macbeth decides to kill him during a banquet.13 At this point, Boece lists the Stuart kings springing from Banquo, originator of the noble line of the Stuarts.14 A share in this ancestry is what the Stewards of Ely claimed for themselves.

Whereas Ancestry.com now challenges its users to discover “their unique family history,” pre-eighteenth-century genealogies aimed to state not so much individuality per se, but in relation to the kinship links of a society. The “protection” bestowed by an ancestor–even more by an ancestor of uncertain origins and with an aura of myth–determined an identity based on an individual lineage, which was also inscribed within a broader social community.15 The increasing stress on the reliability of historical sources in genealogical practice would eventually erase from family trees many figures like Banquo, whose historicity might have been believed, but could not be fully proved.

~ Dr Sara Trevisan is currently a Solmsen Fellow at the Institute for Research in the Humanities, University of Wisconsin–Madison. She has published on early modern literature and intellectual history and is writing a book on genealogy and the myth-making of British absolutism in the early Stuart period.

1 Jerome de Groot, “On Genealogy,” The Public Historian

2 Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, L’ombre des ancêtres (Paris: Fayard, 2000), 189-90.

3 For a detailed discussion, see J.H. Round, Studies in Peerage and Family History (New York: Longmans, 1901), 131-46. Elizabeth Cromwell, mother of Oliver Cromwell, was a member of this family.

4 The pivotal ancestor was Sir John Steward, an alleged relation of the Royal Stuarts, who settled in England in the fifteenth century. See Walter Rye, “The Steward Genealogy and Cromwell’s ‘Royal Descent,'” The Genealogist 2 (1885), 34-42: 34, accessed June 4, 2015.

5 British Library Add MS 15,644, ff. 72-8; Round, Studies in Peerage, 142.

6 Round, Studies in Peerage, 141-44.

7 Round, Studies in Peerage, 140.

8 For a detailed discussion of the various phases of this process, see Round, Studies in Peerage, 140-44, from which this account is drawn.

9 For a discussion of the painted glass, see John Bain, “Notes on a Piece of Painted Glass Within a Genealogical Tree of the Family of Stewart,” Archaeological Journal 35 (1878), 399-401, accessed June 4, 2015.

10 British Library Add MS 15,644, f. 71r.

11 British Library Add MS 15,644, f. 71r.

12 Michel Nassiet, Parenté, noblesse et États dynastiques (XVe-XVIe siècles) (Paris: EHESS, 2000), 32.

13 Hector Boece, Scotuem Histoirea (Paris, 1575 [1527]), Book XII, par. 2, accessed June 3, 2015.

15 Pierre Ragon, “Introduction. De l’invention de la mémoire,” in Les généalogies imaginaires. Ancêtres, lignages et communautés idéales (XVIe-XXe siècle), ed. P. Ragon (Mont Saint-Aignan: Publications des universités de Rouen et du Havre, 2007), 9-18: 13.

Thanks for sharing was a useful

This is a very interesting article. However, it would be appropriate for the author to re-assess the validity of the Steward genealogy, for the following reasons:

1. Although the window implies (but does not appear to state explicitly) the Banquo origin, this should be dismissed immediately and not used to discredit the genealogy from the late 13th Century onwards. That would also discredit the Royal line, which is well documented! Banquo did not exist. He was inserted in Hector Boece’s chronicle and taken up by Raphael Holinshed, from whom Shakespeare took his histories. The true history was discovered by Horace Round and updated and corrected a few years ago by Paul Fox. The origin of the family as dapifers (stewards) to the Archbishops of Dol in Brittany is now well documented.

2. Anyone who has studied the codex (British Library Add MS 15644) knows how much work was put into this document by Simeon and Augustine Steward and how a ‘forgery’ (Walter Rye’s intemperate word) would have damaged their own reputations, so it is difficult to believe that it is not genuine. I commend the paper by Sir Henry Allan Holden Steward (Cambridge Antiquarian Society Proceedings XXVII for 1924-25 pp 86-122) for a very detailed refutation of Rye’s comments.

It is helpful that Henry Wharton’s Anglia Sacra 1691 and some of the Harleian series of Visitations are now available on line as Google digitisations. The Wharton contains Prior/Dean Robert Steward’s genealogy, based on the codex, appended as part of his section on the diocese of Ely.

Paul Stewart Ives

Dear Mr Ives,

Thank you for your comments on my article. I would like to add my own observations on it. By saying that I should ‘re-assess the validity’ of the genealogy you suggest that I have a low opinion of it. Far from it. The way in which it brings together varying degrees of genealogical plausibility within one linear tree makes it a great example for my research, as the article’s title anticipates. I am studying the presence of mythical ancestry in Anglo-Scottish royal pedigrees within a broader European context. Mythical ancestry is an important aspect of European Renaissance culture, and entered the works of important scholars of the time, like Erasmus, William Camden, Annius of Viterbo, Florian de Ocampo, and so on. In so doing I follow the path paved by Roberto Bizzocchi’s “Genealogie incredibili”, which discusses the workings of genealogy from antiquity to the European Renaissance, and the intellectual background behind the use of mythical ancestors for the royalty and the nobility.

Wagner’s “English Genealogy”, and Round’s “Studies in Peerage”, “Peerage and Pedigree”, and “Family Origins”, among others, acknowledge that sixteenth- and seventeenth-century heralds often accepted uncritically the family ancestry data that were given to them, which could also be based on forgeries, the misreading of documents or the invention thereof. So, the Stewards would have been no different to many other families of the time in doing so.

The depiction of the founding ancestor lying at the bottom of the Steward genealogy reprises the medieval model of the biblical Tree of Jesse, a common genealogical scheme amply used in fifteenth-century family trees.

The royal line would not have been at all discredited by Banquo – that’s the point. There is an issue of ‘tradition’ – or ‘received opinion’, as antiquaries called it – and the prestige of antiquity at work in the inclusion of mythical ancestors in royal genealogies. The genealogy discussed in my article dates back to the time in which the reform of genealogical practice towards a stricter method to weigh documentary evidence hadn’t fully developed, as Wagner explains. The historical value of the Stewards’ charter is just contextual information and does not disprove my argument either way. (But on the scholarly importance of forgeries in the Renaissance see Grafton’s “Forgers and Critics”.) There are plenty of majestic pedigrees which contain mythical ancestors. (See one of the Earls of Warwick on the College of Arms website.)

I did mention that Banquo first appeared in Boece’s work, and I am aware of Holinshed’s influence on Shakespeare, whom I used to illustrate that Banquo was still an important figure in relation to the royal Stuarts in the early 1600s. Indeed, in George Owen’s 1604 genealogy for James I, the absence of Banquo’s ancestry is acknowledged and, as in the Stewards’ genealogy, left unaddressed. My interest doesn’t lie in the real identity of these ancestors, as in why Banquo, and mythical ancestors in general, were introduced and kept for so long in such genealogies.