Public historians take on climate change

29 April 2012 – Leah Glaser

conference, public engagement, memory, sense of place, environment, sustainability, international, politics

Historians and Climate Change Panel

Historians and Climate Change Panel

NCPH/OAH Annual Conference, Milwaukee, April 20, 2012

Panelists discussed specific ways historians can think about and contribute to solutions about climate change. Chair Phil Scarpino (IUPUI) began by asking, “Why should historians talk about the future? How do we know climate change is real? What is being lost?” He cited the popular book Collapse by Jared Diamond as an example to historians, because Diamond highlights, for a popular audience, past societies who failed to see problems. Scarpino argued the idea that cultural values are at the base of climate change, and that persuading the public to accept climate change is a cultural problem involving cultural diversity and nature and faith. Writing can have an impact on values and this is where the historian comes in.

Next, Mark Carey (University of Oregon) discussed his review of IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports. He agreed that historians can help in the areas of detection and attribution regarding climate change and that climate change is as much a story of cultural values as science. Historians should collaborate with the scientific community, which enjoys the hegemony and authority on this issue, but historians can find cause/effect, assess impact and change, identify the role of race, gender, class, power, authority, colonialism, and post-colonialism in illuminating the context of climate change. We can provide a framework for who has had authority and embedded agendas on understanding and communicating global warming to the public. Skeptics frame the subject within different parameters. Even science operates in a cultural and historical context.

Rebecca Conard (Middle Tennessee State University) provided an overview of past polices in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom regarding the effects of global warming on cultural resources. She reported that Parks Canada, for example, and little strategy, except a recognition that it should oversee protection of as yet to be identified 50 moments of historic significance in Canada. The American/ NPS response is more natural than cultural and the agency has taken a “systems approach” by addressing climate change within its existing structure and appointing a steering committee. Discussion of climate change in NPS has entailed 1) collaboration with science; 2) adaption of pursuant measures with local knowledge and traditional practices; 3) mitigation: reduce carbon footprint in NPS units, and finally 4) education including initiatives and youth opportunities. NPS has currently deployed 60 students nationwide to work on climate change issues. In the UK, English Heritage, a 17-person commission, has assessed buildings at risk and expanded its list to landscape and archeology sites. Conard suggests that it is time to grant local, not just national authorities power over what can be done. For example, local authorities can document resources at local level to identify what is happening to resources and why things are changing.

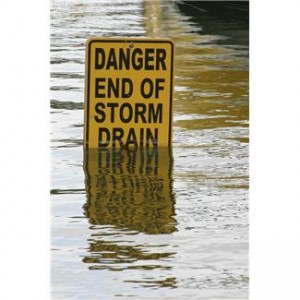

David Glassberg (University of Massachusetts/Amherst) asked historians to consider the plight of “refugee species” who live in a “no analog” world of new ecosystems. He cited the book Nature by Design by Eric Higgs. “What,” he asked, “do historians do without predictable patterns?” Glassberg discussed the role of memory and the way historians talk about memory as an area to which public historians can illuminate this idea and discussion and changing sense of place. Memory binds people to the environment/ to place, but nature is no longer behaving as we remember or how we are accustomed to (hotter, wetter). Histories of a place carry nostalgia and give continuity and depth. We now need to adjust to the new normal. History can offer parables (stories of collapse) but also histories of environmental sustainability and stories of resilience. Narratives can maybe help maintain continuity and connections to a place that no longer behaves the same. Historians can help to heal the broken narrative and offer hope by emphasizing change and resiliency rather than technological/environmental determinism. Histories can emphasize how humans can shape the understanding of our past (and future?).

Finally, Nancy Langston (University of Wisconsin) discussed her research on the Lake Superior Basin, which can serve as a case study for the kind of research historians can conduct on climate change. She also asks, “What is being lost? “ and “What is the history of the human response to change?” She echoes that histories can help encourage a future of resiliency, that history matters because of the intensity of the human response to change and a changing sense of place. Historians can pursue memories of what will be lost and unraveling of complex relationships of humans to their environment.

~ Leah Glaser