Reflecting on “Our Only Alma Mater”

18 April 2019 – Josh Howard

practice, public engagement, 2019 annual meeting, collaboration, African American history, education, NCPH 2019 Awards, consultants, race, labor, National Park Service

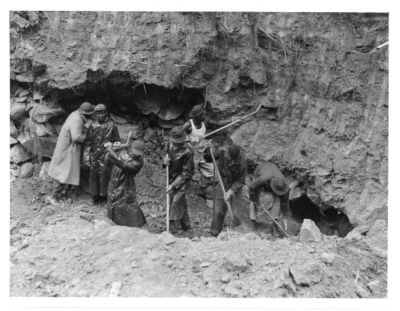

CCC enrollees repairing prism at the C&O Canal. Photo credit: National Archives at College Park.

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of reflective posts written by winners of awards given out at the NCPH 2019 annual meeting in Hartford, Connecticut. Josh Howard of Passel Historical Consulting received the individual “Excellence in Consulting” award.

“We have gathered a lot / From our stay // We have beaten rocks / and are on our weary way. // In our hearts will remain / the teachings of our heavenly Father / And you will always be the same, / Our only Alma Mater”—Frank White, Towpath Journal, 29 June 1939

As a consulting historian with the National Park Service (NPS), I am overjoyed when the product of my research goes beyond aiding site interpretation. Completed a year ago, “Our Only Alma Mater”: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal analyzed labor, environmental, and African American history at the C&O Canal. It honors the legacy of the CCC-enrolled young men who built one of the most visited NPS sites while arguably serving as some of the first federally-employed public historians.

The Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal operated for nearly a century as a critical transportation route paralleling the Potomac River before closing down in the late 1920s. Floods and the growth of railroad networks led to financial problems and ultimately the bankruptcy of the canal company. Neglect led to disrepair, so by the mid-1930s most of the canal was unnavigable and in wretched condition.

A few folks within the federal government envisioned the canal serving a new purpose—recreational tourism. The government purchased the canal, all 184.5 miles, and in 1938 enacted a beautification and renovation plan. Needing a massive amount of labor for such a project, the government dispatched the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to build two CCC camps near Cabin John, Maryland, between the canal and the Potomac River.

A CCC worker holds a mule, which carries a girl on its back while pulling the NPS excursion boat, the “Canal Clipper.” Photo credit: National Archives at College Park

Work focused on the area from Georgetown to just above Great Falls—a span of about twenty-two miles. Both CCC camps at the canal consisted of roughly 200 African American men aged 18 to 25, around ten white military officers and work supervisors, and one African American educational director. They operated from 1938 through 1941. The CCC, like most New Deal agencies, was segregated. Enrollees did it all—cleared the canal prism, leveled the tow walk path, repaired flood damage, and stabilized canal locks and lock houses. Most important to the project at the time was re-watering the canal, which the enrollees accomplished by 1940, and opening the area to recreational tourism by creating walking paths and preserving lock houses (the formerly company-owned homes of C&O Canal employees).

CCC workers open a gate at Lock 5 while another worker clears debris to allow the NPS excursion boat, the “Canal Clipper,” to pass, 1941. Photo credit: National Archives at College Park

Beyond detailing the labor of these men, two interpretations re-orient the way we may think about the CCC at the canal. Enrollees assisted NPS staff with some of the earliest canal boat tours in 1939-41 of what would eventually become C&O Canal National Historical Park. Enrollees guided the tow mules, operated locks, and helped guide the canal boats and did so for the benefit of canal boat tour patrons. In other words, these men were engaged in a living history demonstration. By doing this, these African American men were acting as some of the first public historians at the C&O Canal.

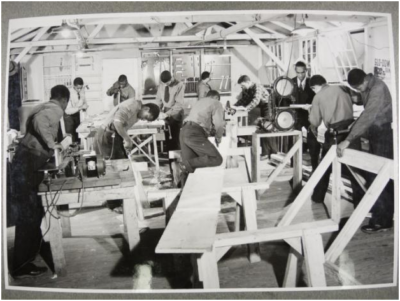

CCC enrollees at a woodworking shop in Cabin John, Maryland. Photo credit: W.J. Mead, National Archives at College Park.

In addition, the two educational officers—who were also the lone African American authority figures at the camps—provided a space where African American enrollees could learn and express themselves. At least one camp offered diverse vocational classes, such as auto repair or typing, alongside courses in literature, mathematics, and African American history. It’s safe to say that this was possibly the first opportunity many of these enrollees had to explore a skilled trade or to study their own history, so the CCC was considered a school by many, as alluded to in Frank White’s poem at the top of this page.

This project began during the summer of 2017 and, while the core project completed in 2018, continues to this day. As I write these words, a project team of volunteers, consultants, and NPS staff are working to install three wayside exhibits at the former site of the CCC camps in modern-day Carderock Recreation Area. I hope to see these in place by July, with a second phase of waysides to follow. None of these projects would be possible without the enthusiastic support of so many at the C&O NHP and C&O Canal Trust, both of which deserve thanks and applause for their continued efforts to interpret diverse histories.

When consulting, the main priority is the client, but, in addition, attention must be given to all other stakeholders. In this case, that means affiliated groups, local communities, and the descendants of the historical subjects. The fact that this project’s subjects were almost all African American young men who were financially poor, at least in the late 1930s, made me extra conscious of doing this work with the utmost respect and due diligence, especially to descendant families.

For me, the most exciting aspect of this work was just that—after searching for months I finally was able to connect with the descendants of a CCC enrollee. Tracking down any of these men was a challenge, so imagine my joy when I found a phone number, dialed it, and heard a voice who said, “Why yes, that was my grandfather.” To exchange both personal and historical stories humanized the canal for me and contributed another history that is people-oriented rather than technological or industrial. I do not want to share their names publicly yet, but I hope they will serve as guests of honor at our wayside exhibit opening in just a few months.

As a final aside, an important component of this work was relying heavily upon the principles of applied history and reflective practice. The project took over a year to complete and involved no less than ten peer reviewers from nearly as many NPS departments. I recognized the potential for the project to get lost in the weeds, so I addressed this problem through iteration, meaning I would intentionally schedule week-long periods of no research, no writing, no editing, and only thinking about the project’s big picture. Was I meeting the core goals? What was I missing? What stakeholders needed to be addressed? What theoretical framework and/or sources could strengthen the project? Altogether, I’m happy with how things turned out, though of course there was room for improvement.

Thank you to NCPH for the opportunity to talk about my work, granting such an award, and—most importantly—sharing the story of the C&O Canal CCC Camps. It’s such a great story that deserves even more research, which the NPS is certainly continuing.

As always, Passel offers consulting services and pro bono support to cultural institutions within Appalachia. We believe strongly in supporting the communities where we live and work and our goal is to assist institutions and individuals making an educational impact, particularly sites and organizations that are the custodians of under-represented histories such as African American, women’s, and labor history. If you are reading this and need anything, please say hello.

~ Josh Howard is a public historian and co-owner of Passel, a historical consulting company based in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. He earned his Ph.D. in public history from Middle Tennessee State University.

thank you for filling in the long-neglected holes in the history of our treasure, the c&o canal, towpath and potomac river.

fascinating that the ccc camps were in cabin john, my neighborhood.

Credit is due to the C&O Canal Association, which first decided to recognize the role of the CCC companies on the restoration of the canal, and especially to Dr. Nancy Benco, research professor of anthropology at George Washington University, who shepherded this project for the Association.