S.103 threatens digital history initiatives around race

27 February 2017 – Kirsten Delegard and Kevin Ehrman-Solberg

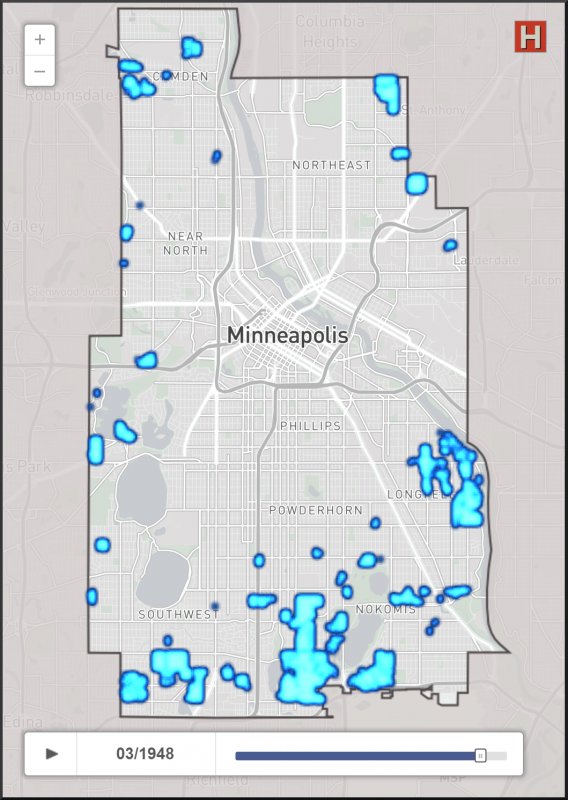

Mapping Prejudice in the Minneapolis Historyapolis project. Screenshot credit: Kirsten Delegard

Not so long ago, few historians knew anything about GIS, or geographic information systems. Many of us saw little need to learn complicated software built on scripting languages and databases. We retreated to the familiar environment of the archives, leaving the technical challenges of GIS to geographers and computer scientists.

This early hesitation disappeared with the realization that this software platform could open an expansive new window on the past. Public historians are now evangelists for GIS, which makes it possible to store massive amounts of historic data, link that information to coordinates on the earth, and display the results in rich and interactive visual environments.

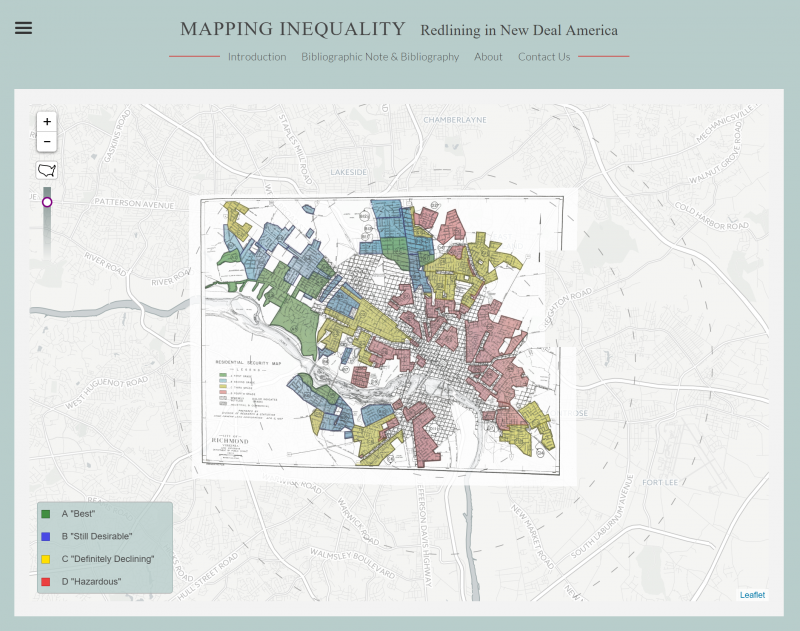

Mapping Inequality. Screenshot credit: Kirsten Delegard.

A compelling example of how GIS can transform our understanding of history can be found in the “Mapping Inequality” project hosted by the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab. This website uses New Deal “redlining” maps to illustrate how federal policy makers “used racial criteria to categorize lending and insurance risks.” Racism, it is clear from this interactive exhibit, was at the core of modern American housing policy.

Historians have long understood the importance of redlining. Yet by leveraging GIS to organize, analyze, and display historic data about this practice, an interdisciplinary team of scholars re-told a familiar story in way that made it accessible for a popular audience. This work received kudos from National Geographic, Slate, National Public Radio and Forbes, where Sarah Bond credited this historic visualization with illuminating how “historical decisions continue to have an impact on the U.S. today.”

The power of GIS to illuminate systemic oppression and institutional racism have also attracted the attention of Congress. But not in a way welcome to scholars.

On January 11, 2017, Senators Mike Lee (Utah) and Marco Rubio (Florida) introduced S.103–115th Congress, the “Local Zoning Decisions Protection Act of 2017.” The language is blunt: “no Federal funds may be used to design, build, maintain, utilize, or provide access to a Federal database of geospatial information on community racial disparities or disparities in access to affordable housing.” A similar bill was also proposed in the House of Representatives.

Public historians need to add this legislation to their already long list of measures to protest. This cannot go unchallenged. These bills are an attempt to fetter historians determined to illuminate the workings of race in America, a central priority for public history today.

Our work with the Mapping Prejudice Project—a collaborative and interdisciplinary effort to map racially restrictive housing covenants in Minneapolis—is inspired by Mapping Inequality as well as the ground-breaking scholarship of historians at the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project at the University of Washington.

If S.103 becomes law, all of this work is endangered. And that is its intent. The legislation builds on a successful effort to bar researchers from studying gun violence. In the 1990s, Congress barred the Centers for Disease Control from collecting data that could be used to “advocate or promote gun control.” Similarly, current administration officials have considered preventing the EPA from conducting research on climate change. Without data, presented in an accessible fashion, ordinary citizens cannot develop fact-based understandings of social challenges. And without public understanding of problems, elected officials will feel little pressure to address threats or inequities.

The legislation aims to choke off federal funding for research on racial disparities. But the impact could be even greater. This ban could halt all geospatial work that uses race as a category of analysis. Most academic institutions conducting this kind of research receive some kind of federal funds.

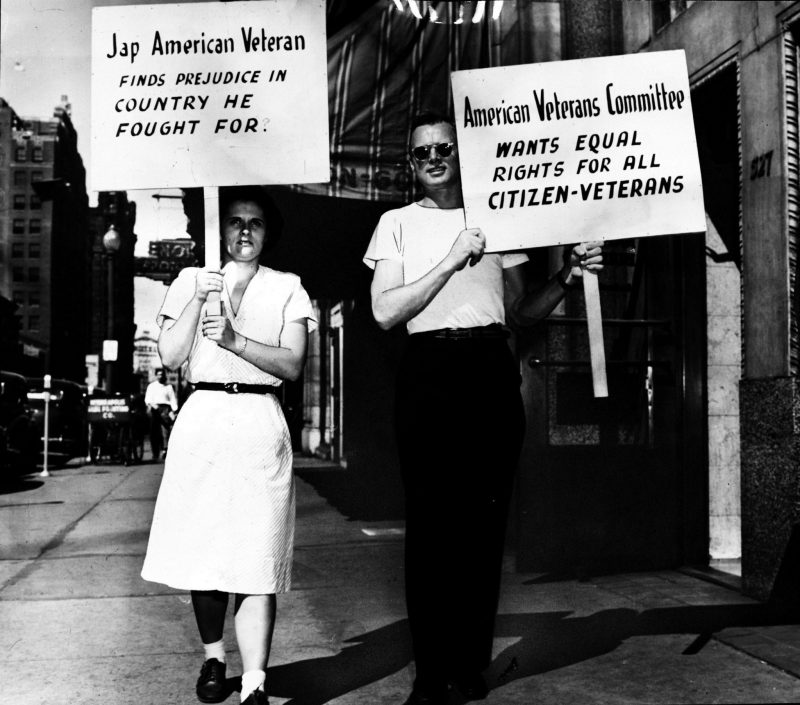

American Veterans Committee members protesting race-based real estate covenants at the Minneapolis Board of Realtors in 1946. Photo credit: Hennepin County Library.

Our nation deserves a courageous account of its history. We need narratives that fearlessly examine the complex legacies of our collective heritage. Such history must reckon with race and racism, historic and contemporary racial disparities. This bill targets anyone who makes this kind of socially-engaged research their mission. It takes aim at those of us determined to use history to do work in the world. As historians and Americans, we unequivocally condemn the proposed legislation.

~ Kirsten Delegard is director of the Historyapolis Project, Augsburg College.

~ Kevin Ehrman-Solberg is an MGIS student in the Geography, Environment and Society department at the University of Minnesota. He is also the project lead for Mapping Prejudice and the GIS director at the Historyapolis Project.

I would like to use part of your article to write letters to my Senator and representatives. We must not let this happen.

Please do! Thank you for being an engaged citizen and active public historian.

Kirsten Delegard

This is a wrong-headed attempt to raise the status of the ghetto dwellers by lowering the status of non-ghettos. It should be defunded and die off.