Sticky notes as tools for public history

09 January 2017 – Evan Faulkenbury

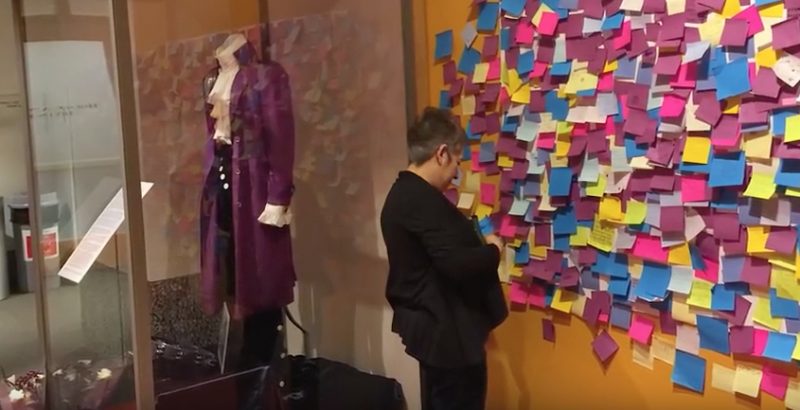

Prince memorial exhibition, Minnesota Historical Society. Photo credit: Screenshot from MHS “Remembering Prince” video

Several years ago, on a visit to the Levine Museum of the New South in Charlotte, North Carolina, I encountered an exhibit that asked me to participate. No, this was not high tech. No selfies, no QR codes, no downloads, just pencil and paper–yellow sticky notes. Many of us use sticky notes in our daily lives for making lists and jotting down ideas, and history museums have utilized them to invite visitor feedback on exhibits for a long time. What caught my attention at the Levine Museum, however, was that in an age of digital innovation and experimentation, something as simple as sticky notes had the power to invite introspection from guests–dozens of multi-colored sticky notes dotted a wall, each with unique hand-writing and each with personal memories.

By no means am I dismissing the importance of interactive digital technologies, but in recalling my experience at the Levine Museum, it made me think: How do other history museums use sticky notes in the twenty-first century? Does writing and reading these notes improve visitor experiences, and if so, how? And what happens to all those sticky notes? Are they thrown out, or preserved as historical artifacts? Dreaming up innovative ideas for turning museums into participatory spaces is nothing new, as Nina Simon and Lilia Ziamou have written, but how exactly have historical sites fostered interactivity by using sticky notes?

Prince memorial exhibition, Minnesota Historical Society. Photo credit: Screenshot from MHS “Remembering Prince” video.

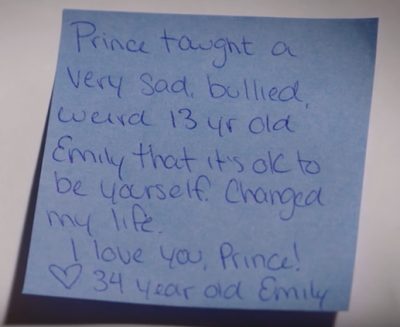

At the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul, Lori Williamson, from the collections department, turned tragedy into a moment of historical reflection after Prince passed away in April 2016. The museum exhibits Prince’s outfit from Purple Rain, and the day after his death, visitors were encouraged to write sticky notes and post them on a wall nearby. In this video, Williamson shared that over 1,000 patrons left memories of what Prince meant to them. One read, “Prince taught a very sad, bullied weird 13 year old Emily that it’s ok to be yourself. Changed my life. I love you, Prince! Love, 34 year old Emily.” Williamson said that the museum has not always kept sticky notes in the past, but it will archive a selection of the Prince memorial notes. “We will add these to the collection, and so people in the future, one hundred years from now or more, will be able to review them and really get a better understanding of what Prince meant to this generation.”

Photo credit: Screenshot of Newseum Pinterest page.

For the Newseum in Washington, D.C., walls can become overcrowded with sticky notes asking patrons to “talk back” to exhibits. Before recycling, the Newseum digitizes selected notes and promotes them on social media. Carrie Christoffersen, curator of collections, pointed out the Newseum’s Pinterest page. As part of the exhibit, JFK: Three Shots Were Fired, which detailed the history of the media’s portrayal of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, the Newseum published several anonymous sticky notes asking patrons to recall where they were when they learned about Kennedy. One visitor wrote, “I was in 6th grade. No one told our class but when we went out in the hall for recess, the janitor was watching a TV. I asked him what happened & he said the President had been shot. I asked if he would die. He answered ‘Only God knows that.’”

Not every museum uses sticky notes; others make available comment sheets that are later typed, preserved, and exhibited as pieces of history themselves. At the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, patrons, upon exiting, can write and leave memories of personal connections and thoughts about the permanent exhibit. According to Jeffrey Carter, the records management officer and institutional records archivist, the museum currently holds 103 boxes of visitor comments stretching back to 1996. Staff members select pertinent quotes, and Carter maintains an electronic document that now exceeds 1,000 pages. “We consider these to be public records and allow researchers to see and copy the original forms as well as the electronic summary,” Carter wrote me in an email. Similarly, at the Richmond National Battlefield Park and the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site in Richmond, Virginia, Andrea DeKoter, chief of interpretation for the National Park Service (NPS) at these two sites, told me that patrons leave comments, and every quarter NPS staff updates a binder of past comments that new visitors can flip through. The binder receives “quite a bit of use,” illustrating that visitors want “to connect with the site and find out how they are a part of the story” and “to leave a piece of [themselves] behind.”

Making use of sticky notes and visitor reflections varies from museum to museum, but what lessons can they give public historians working in the techno-centric twenty-first century? First, sticky notes are an inexpensive, kinetic way for visitors to attach themselves to history that surrounds. Not everyone has a smartphone, and allowing people to handwrite memories is a way to include everyone. Second, sticky notes can be preserved and archived. Unlike the transience of some digital technology, hard copies of memories on sticky notes (or typed out in databases) ensure the preservation of public experiences at historical sites.

I’m no Luddite, and perhaps it feels old-fashioned to suggest sticky notes as tools for public historians, but think of our vast audiences. Draw them in, simply, with colorful sticky paper and pencils. If, for some, that’s all it takes, then it’s an easy, inexpensive, and potentially powerful tool for us to use.

~ Evan Faulkenbury is an assistant professor of history at the State University of New York at Cortland specializing in public history and the civil rights movement in the American South. Subscribe to his podcast The So What? Question and follow him on Twitter @evanfaulkenbury.

Nice post Evan. Good to see someone else finds these post-it notes interesting and useful. I’ve been writing on a similar topic for some time now. Here’s my most recent blog post on the spontaneous boards in New York City (http://jhowardhistory.com/2016/11/18/spontaneous-protest-talk-back-boards/) and a brief post sharing some text mining I did with my dissertation on the talk back boards at Women’s Rights NHP and Seminary Ridge Museum (http://jhowardhistory.com/2016/01/15/what-ive-been-up-to-text-mining/). There should be a brief article in the next Public Historian on Seminary Ridge as well. I’d be more than happy to share my dissertation (Title: “Talking Back with Post-it Notes: Informal Data Collection and Museum Visitors”) or chat more any time.

Hi Josh,

Wow, thanks for sharing…very cool work! I didn’t know anyone was doing deep research on this topic, but I’m glad to find out that you are. Seems like a fascinating angle on public history, remembrance, memory, and museum participation. Hurry up and publish the book! 😛

Evan

Thanks Evan! I’m working on it as we speak 🙂

Ive learn some excellent stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you set to create such a fantastic informative web site. egfcdkckagcadkdg