Bridging the new digital divide: Open records in the age of digital reproduction

02 December 2013 – David Rotenstein

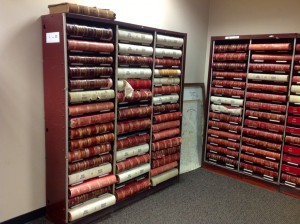

Deed books line the walls of the DeKalb County, Ga., land records research room. Photo credit: David S. Rotenstein.

The depression of 1893 hit the Atlanta Suburban Land Company hard. The Georgia firm, founded in 1890 to develop residential subdivisions along a new six-mile streetcar line linking downtown Atlanta with Decatur to the east, had bought nearly 2,000 acres in its first two years in business. But by 1896, it was more than $100,000 in debt, and a receiver held its assets. In its fall 1896 term, the Fulton County Superior Court ordered the receiver to sell the remaining real estate to settle the debts.

More than a century later, I requested the case files. The Fulton County Clerk employee who handed them to me once they had been retrieved from offsite storage told me that if I wanted copies of the tri-folded documents, I would have to request them from the service counter, and another staff member would photocopy them on a Xerox-type machine for fifty cents apiece.

My request to take flash-free digital photos was rebuffed despite my explanation that it would be better for the aging documents than forcing them flat against a copier’s glass platen and then closing the machine’s cover. I also questioned whether mandatory third-party intervention for copying records was consistent with Georgia’s Open Records Act (O.C.G.A. §50-18-70), and I was invited to speak with the county clerk.

My encounter in November 2013 wasn’t unique. Researchers, reporters, and other individuals using government records have reported similar encounters. In July, after a Greater Washington writer tweeted about being unable to take digital photos of filed building permits, the District of Columbia Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs changed its policy.

Earlier this year, the New York Times reported on the increased use of consumer digital photography in archives, and various academic listservs have debated their use in archives and libraries. The Times article quoted a 2012 report published by the consulting firm Ithaka S+R: “The widespread use of digital cameras and other scanning equipment to capture source materials is perhaps the single most significant shift in research practices among historians,” wrote authors Jennifer Rutner and Roger C. Schonfeld.

But what about government offices like the Fulton County Clerk? I accepted the invitation to speak with Fulton County Superior Court Clerk Cathelene “Tina” Robinson. I met with her and several of her staff to discuss Fulton County’s photoduplication policy and the protection of historical records.

Robinson explained that her office is slowly moving towards digitization, but funding to complete it is elusive. “We understand the importance of maintaining the old records and that’s why we’re going digital,” she said. “The law says these records have to be available. We have to have a way for you to receive copies of these records.”

My request to use my iPhone to photograph the 1896 court case appeared to be consistent with the Georgia Code. The law specifically addresses the use of portable electronic equipment for copying records being inspected by a member of the public: “any person may make photographic copies or other electronic reproductions of the records using suitable portable devices brought to the place of inspection.”

Yet, according to Christopher Davidson, director of the Georgia State Archives and an attorney, the law’s photoduplication provisions may not be triggered unless a request for open records is made. In other words, simply asking for historical records at a county court service counter or pulling a deed book from an open shelf in a records room may not qualify as a legal request to inspect records. At that point, said Davidson, each agency’s rules and procedures are in effect.

Davidson explained in a recent Skype interview,

If it is specifically an open records request. If the researcher has actually gone through the steps for the Open Records Act, then the wording of the Records Act would take effect. But otherwise, the protections or the requirements of the Open Records Act do not take effect.

My interview with Fulton County Clerk Robinson ended when I asked if her office’s procedures were consistent with Georgia’s Open Records Act. A follow-up interview with the Fulton County Attorney was suggested for the following week. Robinson’s chief of staff later emailed to inform me that the county attorney would not be available, and he wrote, “The Clerk is reviewing your questions and said she will send a response back to you at a later date.” My attempts to obtain additional information went unanswered.

Complicating the matter is the question of whether Georgia’s judicial branch is subject to compliance with the Open Records Act. According to Jim Walls, a journalist who previously was the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s lead investigative reporter, Georgia’s courts operate under their own rules for making records — case files and land records — available to the public.

“They say it applies to the administrative branch of government but not to the judiciary, and the legislature’s specifically written themselves out of it,” Wall explained in a recent interview. “So I’m not totally certain that the Open Records Act would even apply to old court files.”

In a recent Center for Public Integrity survey, Wall gave Georgia a failing grade for transparency and access to public records. He was especially critical of the courts for their policies. “The way it applies or doesn’t apply to the judiciary is very nebulous,” Wall said as he described the survey results.

Setting aside the larger legal question of whether Georgia’s courts fall under the state’s Open Records Act when it comes to making records available to researchers, Fulton County’s policies, like those in other jurisdictions around the nation, have not kept pace with changing technologies. Though many courthouses still confiscate cameras and digital recorders or deputies deny access to people carrying them, they allow people to enter carrying smartphones with better audio and video recording capabilities than many mobile newsgathering teams carried a generation ago.

Public historians and professionals require unfettered access to public records. These information consumers must have an economical means to collect data in ways that ensure the conservation and preservation of irreplaceable primary materials. Advances in digital technology have streamlined research and made it more economical and sustainable (e.g., digital images require no paper, chemicals, or AC power). Digital reproduction also reduces the number of times documents are handled and manipulated over copiers. What are your thoughts and experiences in the field? Let us know in the comments.

~ David S. Rotenstein (Historian for Hire) is an independent consultant working in Atlanta, Washington DC, and beyond.

In my experience, I’ve found that the reception to devices like smartphones and mobile scanners is mixed, and varies from place to place. I’ve also found that there is often an economic incentive for repositories to deny the use of such devices – namely, the prices charged for copies. I have done research at a few institutions with this policy, and it is quite honestly frustrating. Although I see both sides for the argument, I think that access to information is most important. It does no use to keep and preserve court records, in this instance, if researchers are not allowed to easily and cheaply obtain personal copies of the information they contain.