Place-based epistemology: This is your brain on historic sites

25 May 2015 – Michelle McClellan

The summer before last, I found myself driving around the back roads of DeSmet, South Dakota, with people I barely knew but with whom I felt a kinship based on our mutual devotion to Laura Ingalls Wilder and her Little House books. We periodically stopped the car, got out, and gazed in rapt attention at….the prairie. Occasionally a fence line or post marked the spot, but sometimes our destination had been determined by the odometer, and there was nothing on the landscape to distinguish that spot from any other. Nevertheless, we oohed and ahhed in appreciation because this place had been the homestead claim of one or another of the people Wilder described in her books. By being there, right there, we hoped we just might move through time. Formally designated historic sites exemplify and capitalize on this connection between place and time. In Philadelphia, Cliveden, a historic site owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, hosts an annual re-enactment of the 1777 Battle of Germantown that draws thousands of participants and spectators every year. A local businessman, who is a long-time supporter of the event, emphasizes the significance of having the battle performed where it actually happened. For this man, the location is key, bringing with it the power to create reality. “What you’re seeing is something that actually took place on this site,” he emphasized. “You’re not looking at make-believe. This is it, baby!”

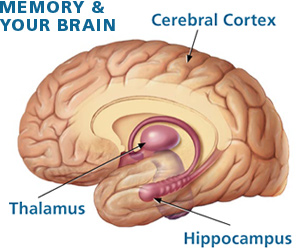

Historic site administrators, re-enactors, heritage tourists, and now neuroscientists recognize how important places can be in shaping memories and our sense of history. Animal research has allowed scientists to map how “place cells” in the part of the brain called the hippocampus are involved in memory and emotion as well as in spatial navigation. This finding is hardly surprising to those of us who have felt how intensely memories can be triggered when we return to childhood haunts. The solidity of buildings and the kinetic and sensory components of moving through space all contribute to a sense of authenticity and reliability.

The “power of place” is not something to be taken lightly, especially since physical settings can mislead as well as illuminate. For one thing, places contain a multitude of stories and voices; highlighting one can serve to obscure others. At Cliveden, an award-winning series of initiatives now expands the interpretation of the site well beyond the one-day battle, looking at labor practices, race relations, and twentieth-century history, just to name a few. Furthermore, both the built environment and “natural” landscapes convey an illusion of permanence that contradicts the reality of historical change. I recently taught a course centered on the Waterloo State Recreation Area, a park in Michigan that covers 20,000 acres. The park was created during the New Deal era. Unemployed young men converted farmland into a setting for city children to enjoy wholesome outdoor recreation.

When my students visited the park, they remarked that being there “brought it to life”–a curious sentiment since neither farmers nor campers are now in evidence. Ironically, although the creation of Waterloo was influenced by idealized notions of rural life, its development required the removal of agricultural families and erased their stories from a celebratory narrative of conservation and stewardship. As scholars such as William Cronon and Anne Mitchell Whisnant have noted about the Apostle Islands and the Blue Ridge Parkway, respectively, the creation of “wilderness” can be so convincing that a casual visitor would never know that people had once lived and worked there.

So how can we learn to “read” places accurately and harness the power of place to enrich our understanding of history? Steven Conn has written about what he calls “object-based epistemology,” the belief that knowledge inheres in objects and that their tangibility represents a kind of pure reality or even truth. Akin to this, I believe, is “place-based epistemology,” the faith that being in a particular location brings us closer to events that happened there, that we can know and understand experiences from the past better if we can go to the places where they occurred. We hear this in our language: “It made me feel like I was really there,” a heritage tourist will often say. Because you are there–and there may be the closest you can get to then.

For “bonnetheads,” as devoted Little House fans are known, Wilder’s lyrical descriptions of the woods and prairies of her childhood impart a sense of familiarity with those settings even before we visit. And while not everyone spends her summer vacation searching for unmarked homestead claims, tens of thousands of visitors travel to Little House sites each year. The overwhelming popularity of Pioneer Girl–a newly published, annotated version of a memoir that Wilder wrote before embarking on the Little House series–reflects the continuing power of place-based storytelling.

But if the Little House books invite us to explore particular settings, how can we reverse the equation so that places prompt our curiosity about history? In his Place, Race, and Story: Essays on the Past and Future of Historic Preservation, Ned Kaufman offers the concepts of “storysite” and “storyscape,” urging us to connect narratives and landscapes. These are very useful tools for historic preservation and community building, but often–as with my jaunt around the prairie or the activities at Cliveden demonstrate–actually appreciating history in place requires background knowledge, professional expertise, formally recognized sites–or all three. Architectural historians, cultural geographers, folklorists, and others can help us all cultivate “landscape literacy” so that we can recognize the stories all around us in our everyday lives.

~ Michelle McClellan is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Michigan.

Thanks for the note about misleading power. I teach cultural geography when not managing the museum here, and love to take a class or tour group to the Cumberland Gap National Park to see “nature”. I love to watch them begin to discover non-natural evidence of past uses of this space. The greatest joy is to hear a past visitor or student say they do not see the outdoors the same again.

I’ve definitely felt the “power of place” just from being on the site of something significant, even if the site has changed a good bit over time. I’m sure that those feelings are largely psychosomatic, since I’ve often built up the importance of “standing on that ground” in my mind so much, by the time I get there, that it usually takes an awful lot of traffic noise or commercialism to diminish it for me. Heading my list so far: the probable site of Powhatan’s lodge, where the famous Pocahontas/John Smith legend was born . . . Jumonville Glen, on a gray, cool day, all by myself, looking up into the tree line where Washington and his Indian allies were concealed . . . Lexington Green, standing approximately where the rebels stood, watching their king’s army approaching on the road, minutes before the first shots rang out . . . the edge of the woods across the field from Cemetery Ridge, where Pickett’s men nervously waited for the command to start, stepping off into oblivion . . .

Visiting these places after you’re read about them is a valuable and important part of understanding them, I think.