Documenting resilience and community healing in Orlando

28 August 2017 – Melissa Barthelemy

Bennett Barthelemy taking a photograph of memorial in front of Pulse Nightclub. Photo credit: Melissa Barthelemy.

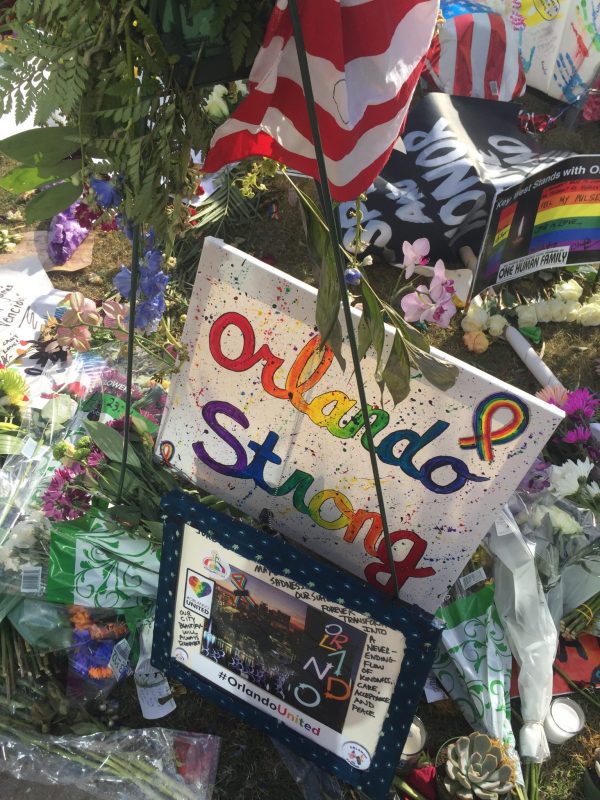

In June, my brother and I traveled from Santa Barbara, California to Orlando, Florida to help document the one-year remembrance events and exhibitions honoring the victims, survivors, and all those affected by the Pulse Nightclub shooting. On June 12, 2016, forty-nine people were killed and sixty-eight people were injured by a gunman during a Latinx Night at Pulse, a gay (LGBTQ+) nightclub. As we walked up to the temporary memorial site, we saw the large black and white Pulse sign overhead and hundreds of people milling about, reading the messages and signs draped on the security fencing around the nightclub. Loved ones knelt down to light numerous candles and to leave bouquets of flowers, condolence cards and letters, rosaries, teddy bears, and handmade artwork. Families wore t-shirts with photographs of their loved ones silk screened on the front and they gathered for group photos. Comfort dogs and even a therapy pony were on hand for people to pet and hug. There was generally a hushed tone and lots of strangers hugging one another. The numerous and vibrant rainbow flags and clothing reminded me of an LGBTQ+ Pride event, but the somber mood indicated this was a mournful showing of pride, a story about resilience, community, and the power of love to overcome hate.

Therapy dog from Comfort Dog Ministry, Lutheran Church Charities. Photo credit: Bennett Barthelemy.

My brother, Bennett Barthelemy, is a professional photojournalist and I am a doctoral candidate in public history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Several months after the shooting occurred, I began advising the mayor’s office of the City of Orlando regarding response efforts and memorialization projects. I have first-hand experience in this type of work because three years ago, a twenty-two-year-old went on a violent rampage in Isla Vista, the residential and commercial district that adjoins the UC Santa Barbara campus. He killed six UCSB students and injured fourteen other individuals. In the wake of this tragedy I worked closely with the campus administration and the families and friends of the victims. I initiated a project to collect the condolence items left at the four spontaneous memorial sites and to create an archive in our department of Special Research Collections at the UCSB Library. I also curated a 6,000-square-foot exhibit for the one-year memorial anniversary. This work has become the basis of my dissertation and has led to my work with archivists around the nation to develop ways to better support those tasked with managing these condolence collections amidst public tragedy.

Condolence items. Photo credit: Frank Billingsley.

There are a number of memorial efforts underway in Orlando. Barbara Poma, owner of the Pulse Nightclub, founded the onePULSE Foundation Memorial to create a permanent memorial and museum to honor those who were killed and injured along with the first responders and healthcare professionals who cared for the victims. One person who has played an instrumental role in Pulse memorial efforts is Pamela Schwartz, the chief curator of the Orange County Regional History Center, and an advisory council member for the onePULSE Foundation Memorial. During an oral history interview, Schwartz confided that within hours of hearing about the horrible shooting she realized that it would be essential to create an action plan for documenting the unfolding tragedy and for collecting the condolence items that would invariably be left at sites of mourning.

Under Schwartz’s leadership, the One Orlando Collection Initiative was formed in partnership with the Orange County Regional History Center, Orange County Government, the City of Orlando, the Historical Society of Central Florida, and other stakeholders. Schwartz and her team collected over 5,000 artifacts from the memorial sites that appeared in Orlando, as well as condolence items received in the mail. They also conducted fifty oral history interviews with family members of victims, survivors, first responders, and city officials—and their collection grows by the day.

During the interview, Schwartz detailed the often invisible labor that she and her team performed at these spontaneous memorial sites over the course of weeks: removing thousands of deteriorated flowers and transporting them to Leu Gardens, a site owned by the City of Orlando, where they were turned into compost that was used to nourish gardens all over the city; scraping wax from candles off concrete sidewalks so that pedestrians wouldn’t slip in the rain; and keeping burning candles away from flammable items.

Staff underneath the rain canopy, preparing artifacts for transportation. Photo credit: Courtesy of Orange County Regional History Center.

To protect the condolence items and memorials from Orlando’s near-daily afternoon rain showers, Schwartz and her team set up canopy shelters. They moved delicate objects under these canopies and tried to dry the artifacts out as best they could for future preservation. I also heard stories about a homeless man who helped care for the largest memorial site, lighting the candles each night for weeks on end. This serves as a reminder that these sites belong to everyone and no one at the same time. It is difficult to put into words how intensely emotional and meaningful the experience of caring for temporary memorial sites, collecting and preserving artifacts, and working with families and friends of victims can be. It is an immense responsibility that one cannot fully prepare for.

For the one-year memorial anniversary, hundreds of family members of victims and survivors toured an exhibit curated by Schwartz called “One Year Later: Reflecting on Orlando’s Pulse Nightclub Massacre.” The exhibit commemorated “one year of pain, grief, loss, love, fear, resilience, coping, and community.” Patrons were invited to “recall the heroes in our midst and the ways our city banded together in defiance of hate; to support all those who continue to live through this nightmare; to remember the murdered and hold the families of the victims in your hearts.” The exhibit featured a representative sample of the condolence artifacts that had been collected, including free standing wooden crosses that had been made and personalized in honor of each victim, and exhibit cases filled with rosaries and other religious iconography. There were also sections that focused on the healing power of art and music, messages and signs from around the nation and the world, and the roles of first responders and mental health service providers.

Schwartz consulted some of the victims’ families when deciding what to include and highlight in the exhibit. However, she told me that few of the hundreds of families, friends, and survivors who attended the private viewing knew who had saved the artifacts or understood how the artifacts had been preserved. Some friends and family members asked for permanent markers so that they could add their names and messages to memorial items on exhibit that had been created in memory of their loved one. Schwartz and her staff explained that artifacts are preserved in the same state that they were in when they were collected and she directed them to a banner specific to the exhibit where visitors could leave messages and sign their names. Condolence exhibits such as this one engage the community in profound ways. They bring the process full circle so that people can see the things they created and left at spontaneous memorial sites. They also speak to our humanity by individualizing each death and reminding us that behind each person who is killed or injured is a loving community that is suffering from the deeply personal loss.

The needs of the community of Orlando are still great. With forty-nine killed, sixty-eight injured, and over 250 eyewitnesses, these wounds will last a lifetime. Community healing takes both time and resources. The City of Orlando, Orange County Government, and Heart of Florida United Way partnered to create an Orlando United Assistance Center (OUAC) where those who have been affected by the Pulse shooting can receive support and resources. The OUAC helped arrange transportation and accommodations for the many family members of victims who traveled from Puerto Rico and South America to attend the one-year memorial anniversary. The OUAC also provides services and referrals year round and will continue to do so for years to come.

Painted rock at Pulse Nightclub spontaneous memorial site. Photo credit: Melissa Barthelemy.

In addition to providing these basic needs, there is also a need for historians to support the work being done in Orlando. With so many victims and survivors, and with such a large number of first responders and affected community members, there are many people who are eager to tell their stories. There is a palpable need to preserve the immediate past for the benefit of the present and the future. We cannot underestimate the importance of memory making and memorialization efforts for communities that have suffered public tragedies, and especially those who have suffered a long history of marginalization and discrimination. It is my hope that professional historical organizations and federal government agencies will help provide funding and resources to those in Orlando doing this work.

One of the most moving memorial items I saw along the remembrance fence in front of Pulse Nightclub was a printed rock that I discussed with Sara Grossman, a friend of victim Christopher Andrew Leinonen. The rock said, “For all those who just wanted to dance.” It is a reminder of the innocence of those who were killed and injured. No community can fully prevent a mass shooting or other terrorist attack, but what matters is how we respond—and how we document that story of resilience, compassion, and hope.

~ Melissa Barthelemy is a doctoral candidate in public history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her dissertation focuses on memorial projects in the wake of school shootings and other public tragedies. Since June 2014, she has served as the project manager for the May 23, 2014 Isla Vista Memorial Collection Project at UCSB.

some beautiful light to be found in all this darkness…thanks, Melissa.

Thank you Kerri, it is deeply touching to be able to do this work with the community.

Melissa and Bennett Thank You so very much ! #honoringwithaction ! Greatly appreciate it !

Thank you Mayra. We really appreciate and admire all of the work you are doing in Orlando, and the positive messages you are helping spread around the world. Take good care.