Generative AI and historical authority

19 October 2023 – Adina Langer

We all know what it sounds like—that voice you hear in your head when you read museum labels. It is confident, assured, and direct. It is friendly, concise, relevant, and eminently believable. And, despite many public historians’ attempts to make our work more transparent and let go of traditional didactic authority, the comforting institutional voice is a reason why museums remain among the most trusted sources for historical information decades in the running, regardless of increasing concern about veracity in the wider information environment. And now that authoritative voice has a new cousin: It sounds an awful lot like ChatGPT.

“Open MInd,” Detail of Jaume Plensa’s sculpture “WE,” 2009. Image credit: Anders Sandberg. CC BY 2.0

Despite some boosterish coverage early on, there have been murmurings of unease in our field about generative AI, but much of the coverage remains relatively optimistic. Why, then, should ChatGPT’s authoritative voice be a cause for concern? Where Wikipedia (first distrusted by our field but now seen as a useful tool for public historians) and Web 2.0 (the Internet’s twenty-first-century evolution to include two-way conversation and user-generated content) emphasize sourcing and transparency, the current movement toward algorithmic production and generative AI suggests that a new paradigm is emerging for information-gathering and transmission. This has not gone unnoticed by prominent Wikipedians. In turn, this new paradigm poses a problem for digital literacy, particularly in the area of evaluating textual authority and understanding historical epistemology, especially given people’s habits of trust in digital environments.

Illustration by Mohammad Assan (2021). CC0

The problem is that most people don’t understand how generative AI works. Instead, when they type a question into ChatGPT, they hear the Voice of the Internet speaking to them, and, like Museum Voice, it sounds authoritative and accurate. To help our public better understand this new resource, it is essential that public historians make an effort to understand it for ourselves.

ChatGPT is not a web crawler or a replacement for Google. It is a text generator trained on a corpus that includes books, articles, web pages, and more, all produced by humans before 2021. Its primary purpose is to mimic the human voice by synthesizing the most likely content that would be produced based on a particular query—not to deliver accurate information, per se. Ultimately, generative AI has the potential to be a powerful tool to see patterns, similar to distant reading techniques used in the digital humanities. However, despite being produced by a company called OpenAI, the code for ChatGPT has not been released to the public. Instead, people are invited to test out the proprietary chatbot by signing up with a username and password. Thus, the way that ChatGPT uses sources remains opaque.

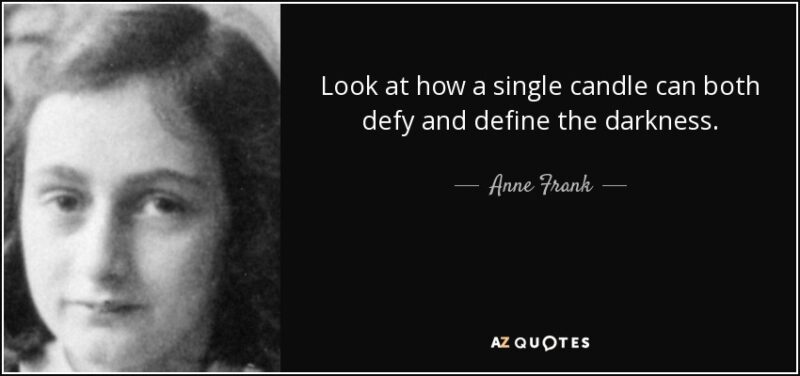

It is also unclear when and why the technology changes its answers. Take, for example, a query I conducted in July 2023. Aware of a persistently misattributed Anne Frank quotation, I asked the chatbot: “Who said, ‘Look at how a single candle both defies and defines the darkness’?” It returned the following answer:

The quote, “Look at how a single candle both defies and defines the darkness,” is attributed to Anne Frank. Anne Frank was a Jewish girl who gained international fame posthumously for her diary, which she wrote while hiding from the Nazis during World War II. The quote reflects her perspective on hope and the power of even a small light in the midst of darkness.

I then asked, “Did Anne Frank say, ‘Look at how a single candle both defies and defines the darkness’?” and the chatbot apologized (in proper human-mimicking form) for providing me with inaccurate information before. When I asked it the same question again, it attributed the quote to author Anne Hillman.

Meme with the quote “Look at how a single candle can both defy and define the darkness” attributed to Anne Frank, beside a photo of her face. Image credit: AZ Quotes.

Our conversation continued from there, with ChatGPT switching back and forth between attributing the quote to Anne Frank or Anne Hillman. I finally asked, “Why do people think that Anne Frank said, ‘Look at how a single candle can both defy and define the darkness’?” The chatbot stated that this seemed like a case of misattribution or misinterpretation:

It’s worth noting that misattributions of quotes are not uncommon, and they can occur when a powerful statement becomes associated with a well-known figure, even if there is no direct evidence connecting them to the quote.

Notably, when I asked ChatGPT the same questions on August 18, 2023, it first said the quote “is attributed” to Anne Frank and then apologized and warned me that “It’s important to be cautious of misattributed quotes and to verify their sources before accepting them as accurate.”

Without my historical training, I might not think to go past the initial response. Instead, I might take the attribution at face value, like so many people have before, and thus continue to perpetuate the same false information. Although ChatGPT’s responses in our conversation appear like corrections, I can’t know whether they were prompted entirely by the form of my questions, or by their repetition. Perhaps the chatbot was responding to the fact that I kept asking the question over and over by changing its answer, based on the tendency of humans in conversation to adjust answers when challenged more than once on their preliminary responses. This ability to mimic intelligence is what makes ChatGPT so effective at “sounding” authoritative without adhering to any disciplinary standard.

Although this is a relatively low-stakes example, it is worth considering as we imagine a future in which AI-generated text proliferates and joins the corpus of human-produced text that currently makes up our available source material for research and interpretation. We’ve already witnessed the ability of the internet to proliferate and perpetuate misinformation, and the challenges this poses to a novice researcher or purely open-minded information consumer. Imagine a future when AI trains itself on a corpus of text that includes terabytes of AI-generated text based only on a prior corpus of human-produced text. With a larger and larger pool of inaccurate AI-generated text, might the inaccuracy become self-reinforcing?

For public historians, the problem lies in a culture of information consumption that accepts authoritative-sounding content at face value (or doubts all information equally) rather than pushing for the tedious process of source evaluation that enables historians and curators to interpret the past with confidence. The responsibility, then, lies with us to extend and enhance the ways we educate our publics about information literacy. Perhaps if we focus energy on sharing how and why we adhere to certain professional standards of sourcing, corroboration, and bias analysis, our publics will understand why we can write with confidence in the “authoritative” voice of the museum label and historical marker. Then, maybe, they’ll understand why they need to limit their trust of such authoritative-sounding text to that produced by people who employ transparent historical methods.

I’ve seen some educators begin to create exercises to help students navigate the “uncanny valley” of generative AI with historical thinking skills, and I’ve seen museums begin to look at the problem head-on by annotating text created with ChatGPT. What are some other ways we can work to illuminate this issue and educate our publics? I look forward to seeing the conversation unfold on History@Work; just be sure to let us know if you wrote your post with ChatGPT!

~Adina Langer is a Georgia-based public historian and museum curator and has served as a co-editor of History@Work since 2012. Her edited anthology Storytelling in Museums was published in 2022. You can find her on the web at www.artiflection.com.

Very nicely stated. Thanks for taking the time to think about, and write, about this topic. I think we should note, when talking (and writing) about this topic, that different generative AIs will provide different types and qualities of answers. Checking your sources has become even more important now.