Historic Sites and the Root Causes of Environmental Injustice

07 December 2021 – Braden Paynter

The Tribal Historic Preservation Office of the White Earth Band of the Ojibwe works to protect wild rice sources from development, pipelines, and a changing climate. Working with a local church to explore the church’s role removing White Earth children has led to the modern parishioners becoming involved in wild rice preservation. Image credit: White Earth Tribal Historic Preservation Office

Editor’s note: This is our third installment of the “Public Historians in Our Climate Emergency” series.

Historic sites have a critical role to play in advancing environmental and climate justice, using history and place to unlock the root causes of both harm and the ongoing resistance to addressing that harm. Historic sites bring resources and perspectives that can directly advance the struggles of scientific and political organizations engaged in climate and environmental justice.

In particular, they are well-positioned to help scientific and political organizations navigate the individual and social identities (identities that are bound up with the root drivers of the climate crisis—capitalism, colonialism, racism, and sexism) that influence how environmental information is received or rejected. Untangling these drivers and core identities is a challenging task, but guiding hard conversations is what historic sites are well equipped to do. As powerful places that ground and center people, offer access to emotional stories and new perspectives, and build skills and relationships to enhance our understanding of ourselves and the world around us, historic sites offer access points for making visible and transforming the root causes of environmental injustice and resistance.

The standard model of climate education seeks to prompt action by providing more information about the carbon cycle, human processes of the last 150 years that directly feed that cycle, and current and future impacts of changes to that cycle (see NASA for example). This framing has the virtue of identifying a clear problem and a clear set of solutions for individuals to implement, such as making use of renewable energy, recycling, and alternate transit options. But the framing fails to move beyond appeals to cease harmful behaviors to get at the root causes that drive them and the resistance to changing them. Since humans are driving the climate crisis, addressing root causes means addressing what is driving humans.

The University of Illinois-Chicago’s Rafael Cintrón Ortiz Latino Cultural Center has built dialogues with Spanish-speaking newcomers to the Chicago area to help redefine what it means to be an environmental activist. By drawing on cultural practices and taking on stereotypes and stigmatization head-on, they have helped people recognize and build their capacity to have positive environmental impacts. Screenshot courtesy of the Rafael Cintrón Ortiz Latino Cultural Center.

The problems of climate disruption and the possibilities for climate justice cannot be understood without accounting for the pressures the interlocking systems of capitalism, colonialism, racism, and sexism put people under in the past, and the pressures they put people under today. In seeking to control nature for personal gain or mere survival, no one set out intending to alter the climate of the entire planet, but for centuries they made choices that did so again and again. Where better to try to understand these pressures and choices, as well as the ways people have resisted the pressures, than in the very factories, government buildings, homes, and mines where those choices were made and carried out? Historic sites exist at the intersection of the systemic and personal, past, and present, and do so physically, making tangible those intangible and invisible concepts. To understand why we are where we are, and what we might do about it, we must visit the places where we “live, work, play, learn, and pray” in the past and present to understand where we go in the future. For example, places like the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum or the Baltimore Museum of Industry are windows into how people, lived, worked, and resisted while participating in industries that we understand damaged them and the planet.

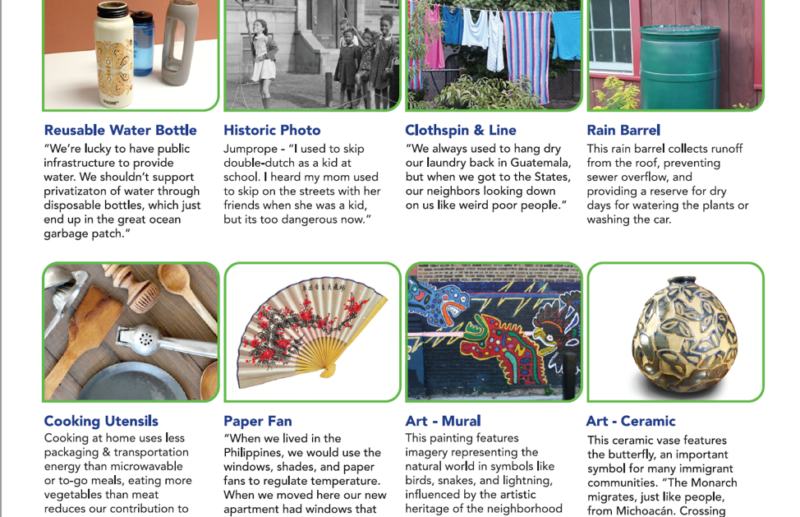

Injustice is, at its root, a product of human choices and human systems. Understanding the scope and depth of those systems can build support for solutions, and understanding the resistance to those solutions requires investigation of the human. For example, the Tribal Historic Preservation Office of the White Earth Band of the Ojibwe has worked with a local church to uncover the role the church played in removing children. Telling that history has enabled deeper relationships and action to counter ongoing threats to the White Earth people and land. And the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Rafael Cintrón Ortiz Latino Cultural Center has worked to remove barriers between Latinx immigrants to the city and the environmental movement by centering the lived experiences, and sustainable skills and cultural practices, of the immigrants.

Seeking to understand the climate crisis through historic sites, we can make visible how individual choices about how to treat the planet and each other always take place in a sea of larger social pressures and group dynamics. Making these pressures visible and understandable helps people to develop cross-group social relationships and meta-cognitive skills that can raise awareness of their implicit biases, as well as offering them new stories and lived experiences that can expand their conceptions of truth and develop new narratives of identity. All are things that historic sites are well-positioned to provide through their social interaction, power of place, dialogic interpretation, and vast depth of stories (both from the past and from other visitors’ lives).

The Baltimore Museum of Industry spans more than 150 years of history including and focusing on the lives of the workers that helped to propel the city: factory workers, printers, assembly line laborers, men who shucked oysters. and women who sewed trousers. Image courtesy of Baltimore Museum of Industry .

The realization of this powerful potential for change is not a given and requires intentional work by historic sites to understand their goals for impact, roles in change-making, and processes for achieving both. This will be new for most historic sites, which have not regularly thought of themselves as actors for justice and climate action and will necessitate at least two foundational reviews. One is examining their theory of justice, and how they can incorporate its components in their day-to-day operations (listen to David Hooker talk about several approaches). The second is understanding their theory of change, and how they can incorporate its components in their efforts to impact the world. With an operating theory of justice and an operating theory of change, historic sites can more intentionally and effectively be a part of justice movements.

The climate crisis challenges us to respond to the legacy of past human choices and consider what legacy our choices will leave. These questions cannot be understood without better scientific understanding of the physical world, but they are, at their core, about humans and the societies we build. Historic sites, as bridges between our pasts, presents, and futures, need to be engaged in helping our societies come to terms with the legacies of harm that drive the climate crisis so that we can all engage in building more just and sustainable futures.

~Braden Paynter is the Director of Methodology and Practice at the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, where he helps sites around the world connect to the information, skills, and relationships they need to support their societies. The Coalition is a network of more than 330 sites in more than 65 countries all committed to using history and place to build more just and humane futures.