History in handwriting: family archives in public history

17 August 2023 – Roman Cain

In the depths of unexplored historical niches, historians often find information scarce in public records and archives, leading them to underutilized family and personal collections. Approaching research from such a personal angle has many benefits, but it’s also important to consider the logistics and ethics of utilizing personal and family records for research. These include difficulties in access, physical organization issues, privacy concerns, interpretation biases, and the increasing complexities of digital preservation. For my thesis research, I’m constructing a biographical narrative and analysis of a journal kept by my great-grandfather, John M. Sant, a B-17 co-pilot in the United States 15th Air Force and prisoner of war during World War II. My grandmother, his daughter, has amassed a large collection of primary sources related to his wartime endeavors. By supplementing these sources with postwar interviews and written accounts from my great-grandfather, the cross-section of genealogy and history allows me to better understand my family and make the work publicly accessible.

About the narrative

On November 3, 1943, John M. Sant, a 20-year-old enlistee from Pennsylvania, graduated from flight school. He flew over thirty-two bomber missions in the 463rd Bomber Group. Sant was shot down twice in 1944—once on April 7 over the Adriatic Sea, where he was rescued, and once over Czechoslovakia on July 7. On that last mission, the crew bailed from the aircraft after gunfire damaged both engines. They were captured by the Germans and held as prisoners of war at Stalag Luft 1. For the next ten months, Sant journaled about daily activities at the camp until his liberation in May 1945. The journal is now the centerpiece of the Skinner Personal Archive which was collected by Mary Skinner, Sant’s daughter.

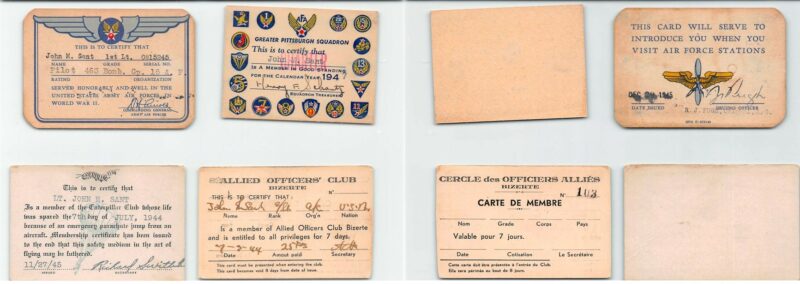

Four small paper cards document Sant’s good standing as a pilot in the Army Air Corps, in Sant’s daughter’s archival collection. Mary Skinner. “Sant Army Air Corps Cards.” Skinner Personal Archives, Danville, Illinois.

In the collection are several handwritten accounts of the event by Sant, letters between Sant and his family, and other documents. In the journal, Sant described the contents of Red Cross parcels, cell layouts, and books he read, with minimal reflection or disclosure of his internal thoughts. While a prisoner, he was under observation by the Germans and kept the journal hidden. Writing mundane things in this hostile environment may seem counterintuitive, but it gave Sant a sense of control, mental escape, and military documentation to refer to once back from war. The last entry contains calculations of backpay owed to Sant by the US after his time in Germany. He never kept another journal after returning from the war.

Sant died in 2020 at 97, unaffected by common cognitive illnesses, so I knew him well beyond reading his journal. While I didn’t begin using Sant’s journal until 2022, talking with Sant during the last twenty years of his life offered a clear picture of his service-oriented, loyal, resilient, and dedicated personality. He served as commander of the Illiana Ex-POW Chapter and as a member of the Vermilion County War Museum, providing personal interviews and open discussions about his time as a POW. These community-first reflections offered additional opportunities to better understand Sant’s story and his approach to the journal.

Personal archival challenges

Black and white photo of a grounded B-17 bomber aircraft, May 10, 2022. Photo credit: BW Square

While personal archives often provide abundant information for historians, there are important considerations to be made when utilizing them. In the case of Sant’s records, having a family connection allowed me easy access to the archive. But other families may not want to share their archives purely for research, even if that researcher is a family member. They may want to uphold a relative’s image, especially if the archive includes an unflattering narrative. Further, family members close to the subject might find researcher meetings and interviews inconvenient or upsetting. Other logistical issues may arise, as private collections can be less organized and more challenging to preserve than publicly-held archives. I discovered this while trying to find the letters Sant sent to his family. I knew they existed because of a single digital copy, but finding the originals proved to be a challenge in the unsystematic arrangement of files. My family spent several months meticulously digitizing most of Sant’s documents, but not all personal collections are or can be so well preserved, especially if the documents are fragile or if the owners struggle with digitization.

Ethically, there may be privacy concerns with personal archives, especially if they are recent or contain sensitive information about living people. Sant’s diary is almost eighty years old and he composed the journal before having his own family. Thus, there was little risk in finding potentially sensitive or incriminating details about living family, making it easier for his daughter to allow me to utilize the source academically. A significant ethical issue I’ve faced working with Sant’s journal is something all historians using family archives should consider: the risks of personal connections and bias. Proximity is a significant motivator of study, and no matter how distantly related, connection to the subject can influence a researcher’s interpretation. I’ve found it crucial to remember that while Sant’s source volume is unique, his capture and wartime experiences mirror thousands of other American soldiers. By presenting Sant’s narrative, I’m working broadly to provide a representation of individual realities within the Stalag Luft prisoner-of-war camps. Acknowledging potential bias and placing the journal within its historical context has helped me to remain objective during the research process.

While my family doesn’t have plans to donate the sources, my great-grandfather was very active within the historical community and my work serves as a historical continuation of his narrative. Personal archives expand the range of subjects, enriching our grasp of human history, but given their collaborative nature, it is important to balance the use of such resources with familial wishes. Considering these points, it’s possible to thoughtfully and respectfully present personal archives and engage with the public while also meeting one’s scholarly goals.

~ Roman Cain is a fourth-year BA/MA history student at Ohio State University, specializing in military and public history. Driven by his passion for making history accessible to a wider audience, he has contributed to research projects spanning topics such as airpower history, American homicide rates, and pronoun barriers in the medical field. He is on LinkedIn.

This is well thought out, unique, from the privacy perspective. I look forward to more. I have many family digital records should you wish more genealogy. I will be following.

I have published an article based primarily on a diary kept by my great-aunt when she went to Turkey in 1919, and I dealt with many of these issues. My particular concern was with her anti-Turkey and very strong pro-Armenian comments – typical for American missionary workers at that time. As she remained in Turkey working as a nurse until the 1940s, I presume her attitude to Turkish people changed, but that is not part of her early and only detailed journal.

“‘No more cookies or cake now, “C’est la guerre”’: An American Nurse in Turkey, 1919 to 1920,” Social Sciences and Missions 23, 1 (2010): 94-123.

Wonderful piece, with some really valuable thoughts on personal/family archiving–thanks so much for it. If your family has a change of heart about donating the materials, we would be very interested in accepting them as part of the Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress. We have quite an array of original WWII POW diaries, many of which were donated by veterans interned in the Stalag Luft camps, and Sant’s diary sounds like another fascinating example.