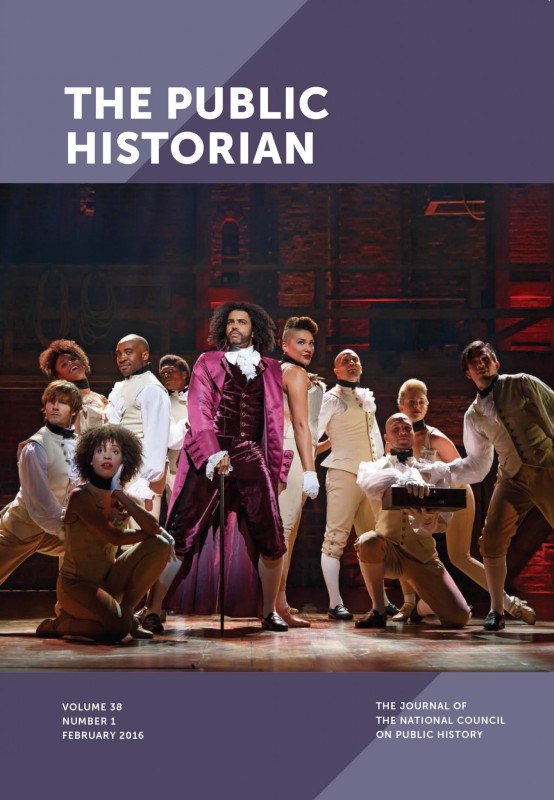

It’s not “just a musical”

10 June 2016 – Lyra D. Monteiro

public engagement, race, The Public Historian, theater, TPH 38.1, "Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton" responses

In the four months since my review of Hamilton: An American Musical was first published in The Public Historian, my ideas have been met with a wide variety of reactions.

In the four months since my review of Hamilton: An American Musical was first published in The Public Historian, my ideas have been met with a wide variety of reactions.

This blog published four responses to the piece, including one by Annette Gordon-Reed, who wrote that my review was an expression of “our duty to use what we know of history and culture to comment” on artistic explorations of the past. I was interviewed by the WBAI radio show Living in Spanglish, Slate.com, and the New York Times. The Pulitzer Prize–winning author and professor Junot Díaz emailed me to say that the review was “immensely important.” The podcast Sad Girls Club dedicated most of an episode to discussing my review.

Not all of the responses have been positive. One blog post accused me of “promoting stereotypes.” On social media and in the comments of many of the pieces mentioned above, several people have diminished me and my work. I was described as “breathtakingly ignorant” and worse. One professional journalist wrote that “for an alleged history expert, she sure doesn’t seem to be terribly well versed in, you know, history,” while the author of the biography on which the musical was based, Ron Chernow, claimed in the New York Times, that both Professor Gordon-Reed’s and my criticisms reflect “an enormous misunderstanding” of the musical. Responding to this volume and range of responses has been a challenge.

I think that much of the public criticism–from the comments on the Slate piece, to the abusive tweets that I quickly blocked–came from a desire to defend the musical against all attacks, which, I’d argue, is based in a fundamental misunderstanding of the role of humanities scholarship. I also believe that we as public historians are among the most responsible for this misunderstanding.

Many of those who have commented on my critique appear to have done so without actually reading either the original article, or even the journalism about it, and instead have focused on the headline or short, out-of-context quotes shared on social media. This is, of course, standard operating procedure in Internet-land. The vast majority of these responses focus on people’s misunderstanding of the role of history and of “what historians do.” Critics pushed back against what they assumed was my “nit-picking over facts,” based on a belief that the historian’s role is to be an empirical policeman over any interpretation of the past.

Hamilton isn’t a history book, they repeatedly told me, it’s a musical. Of course it isn’t entirely accurate, and for me to argue otherwise is absurd.

And so it would be. But my analysis has never been about treating Hamilton as a historical text. Rather, I approach the show as a cultural product, and as such, one that involves choices–artistic as well as historical–about the stories it tells, and how it tells them. There are politics behind every telling of a story–just look at the current furor around the new all-female version of Ghostbusters. These politics become even more pressing when we are discussing a story about the creation of our politics themselves, currently so mythologized as the foundational story of our nation. Indeed, I would be much less likely to have written a critique of the work were this a scholarly book about Alexander Hamilton, as I’m not–and have never claimed to be–a Hamilton scholar. Rather, I am a scholar of the politics of the past; I study why we tell which stories about the past, in what contexts, and what those stories mean.

Some people of color on Twitter and elsewhere asked why I’m only critiquing Hamilton and not other shows–or Hollywood films, for that matter–and have suggested that I’m holding Lin-Manual Miranda, as a person of color, to higher standards than I would a white author. I’m not unconcerned by the ways that other Broadway shows and Hollywood films address race, but the broad critique that most other shows merit is the standard critique of most white-produced American culture, and it has been made before. I believe that Hamilton does merit special attention for the very fact that it is doing something interesting with race–and, furthermore, it is getting a great deal of praise for that. Among that praise is an important claim that deserves very careful analysis: that Hamilton is diversifying the story of the founding of the United States by making it a story that people of color can relate to and claim as their own.

This is not a value-neutral argument. In a country in which those of us who are not white men are still subjected to quotidian discrimination and continue to suffer from the legacies of our oppression on which the country was founded, to tell that history in a way that encourages people of color to feel closer to it only makes it harder for us to see clearly the inequalities that shape our lives. As Jason Allen pointed out in his response to my review on this blog, such a move does, however, work beautifully with the color-blind ideology promoted by white liberals. This musical is guilty of many of the same flaws as the vast majority of stories about the founding era: it glosses over the racism and the sexism involved in the founding our country, as if these were design flaws, not deliberate features.

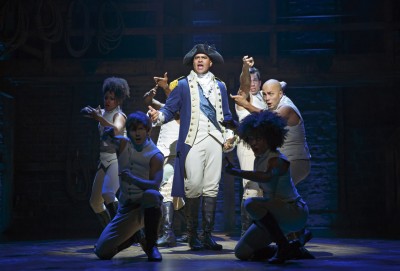

Christopher Jackson as George Washington and the ensemble of Hamilton. Image credit: Joan Marcus.

It is immensely positive to see actors of color star in a huge hit on Broadway, playing more than just what Okieriete Onaodowan, who plays James Madison in Hamilton, described in the book Hamilton: The Revolution, as “[yet] another show about a messed-up black kid.” But Onaodowan is one of three black actors in the show who plays a white, slave-owning current or future president. By cloaking white history in the talent, bodies, and labor of people of color, Hamilton obscures the white supremacist origins of our country. You could argue that the show deserves credit for taking these stories and subverting them through casting that these same white supremacists would find horrifying. However, I’d argue that we’re not yet in a place as a country for this subversion to ultimately be successful. We still look up to the founding fathers as great men who did great things–whose involvement with slavery was shameful, but ultimately forgivable. However subversive the artistic choices, the dominant narrative–one that lauds the founders as great men whose actions created an unequivocally great nation–remains untouched.

Many people seemed surprised that in the Slate interview I stated that despite all of these reservations about the narrative and its message, I still love this show. They shouldn’t be. All our faves are problematic, after all. I believe firmly that art and culture, like people, should not be labeled as “good” or “bad.” It’s more than just okay to like something that also transmits a culturally negative message–in our society, it’s pretty much unavoidable.

I believe that there isn’t a single example of popular culture that doesn’t participate in, and perpetuate in some way, the oppressive systems that surround us. Popular culture is one part of how we establish, justify, and reinforce the norms that structure our society. The role of the public historian is to critique the unnoticed and often unintentional messages contained in popular stories about the past such as Hamilton, and to point out what these stories imply about what we aspire to be. Hamilton is a brilliant, witty, lyrical, musically complex hagiography of a group of white men who deliberately founded this country on principles of white supremacy, creating a legacy of anti-blackness that continues to plague us today. We should not overlook the implications of this fact, even as we hum its tunes.

~ Lyra D. Monteiro is an assistant professor of history and teaches in the graduate program in American studies at Rutgers University—Newark. She is currently working on a book called The Classical Legacy, about the role of concepts of “heritage” in the creation of the United States. She is currently a Create Change Fellow with the Laundromat Project in New York City.

Editor’s note: In “Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton,” published in The Public Historian (38.1), Lyra Monteiro asks, “Is this the history that we most want black and brown youth to connect with–one in which black lives so clearly do not matter?” In this post, Monteiro responds to four posts published by History @ Work responding to her review.