Memory, ideology, practice & place: History at the edges

17 February 2016 – James F. Brooks

Editor’s note: We publish TPH editor James Brooks’s introduction to the February 2016 issue of The Public Historian. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members. Responses to Andrew Hurley’s essay and Lyra Monteiro’s review will be published on History@Work in the coming weeks.

I find it fitting that this issue of The Public Historian features the keynote address that Tiya Miles offered at the 2015 annual meeting of the National Council on Public History. Employing the conference theme of “Public History on the Edge,” Miles’s address, titled “Edges, Ledges, and the Limits of the Craft: Imagining Historical Work beyond the Boundaries,” guided us through the tangle of hidden histories, anxious interpreters, and patient process by which the history of the Vann House grew fully three-dimensional to those who thought they knew it well, to those who visited while memorializing the Cherokee Trail, and to those who descended from the black slaves who once toiled in Chief Vann’s fields. For her, it proved that patience, persistence, and collaboration are central to our practice.

I find it fitting that this issue of The Public Historian features the keynote address that Tiya Miles offered at the 2015 annual meeting of the National Council on Public History. Employing the conference theme of “Public History on the Edge,” Miles’s address, titled “Edges, Ledges, and the Limits of the Craft: Imagining Historical Work beyond the Boundaries,” guided us through the tangle of hidden histories, anxious interpreters, and patient process by which the history of the Vann House grew fully three-dimensional to those who thought they knew it well, to those who visited while memorializing the Cherokee Trail, and to those who descended from the black slaves who once toiled in Chief Vann’s fields. For her, it proved that patience, persistence, and collaboration are central to our practice.

Miles’s essay holds special meaning for me, since Tiya was working through many of the thornier issues she encountered at the Vann House during her 2007-2008 residency at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where I was serving as president. She, her husband, Joseph P. Gone, and their twin girls joined a talented group of ethnographers, psychologists, historians, and archaeologists we hosted that year, and Tiya’s gift for keen insight and courteous critique did much to shape the culture of our intellectual community that year.

Miles’s essay herein takes us across a long decade, during which she struggled with the difficult nexus of memory, ideology, public historical practice, biography, and material culture in a single place. You will find, as always in her work, thoughtful and acute self-critique in her piece, which in turn echoes many of the themes in our other essays. Gilberto Fernandes traces the process by which Portuguese Americans (and Portuguese nationalists in their homeland) invested substantial time and money to a political project that would place Portugal on equal footing with Spain in the “conquest and civilization” of the New World. Anxious about the racially “in-between” status of immigrant Portuguese in early twentieth-century America, these campaigns–which conjoined the right-wing authoritarianism of Estado Novo Portugal after 1927 with immigrant ethnonationalism in the United States–employed public monuments and pronouncements to place Miguel Corte-Real and Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo on equal standing to Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci in the European discovery and settlement of the Americas. Miles and Fernandes remind us that public history may trend in other-than-progressive directions, depending on context and interpretation.

Whereas Miles faced the predicament of rehistoricizing the widely admired Cherokee chief James Vann’s legacy as slaveholder and sexual abuser, Jason Krupar details how a noteworthy coalition of university students, historical society staff, and black activists in Cincinnati worked for more than a decade to recognize the life and works of the remarkable African American former slave, entrepreneur, inventor, and community advocate John P. Parker in community memory and place. Locals led this effort by preventing the sale and destruction of Parker’s home in 1995, which in turn stimulated the engagement of public historians in helping to craft the materials and interpretation that were unveiled in 2009.

The challenges in varieties of public history practice that Miles details find extension in Andrew Hurley’s essay on the limitations associated with new digital technologies faced at the multicampus, multicommunity collaborations undertaken through the Virtual City project in Old North Saint Louis. “Riding the fast moving digital bandwagon is not without its risks and costs,” he cautions, and walks us through the false starts and failures in the project, before ending on the cautionary note that digital media can only be as useful as the quality of the public historians themselves: “it may be that public historians would do well to focus less on what new technology can do than how it might help improve what they’re already doing.”

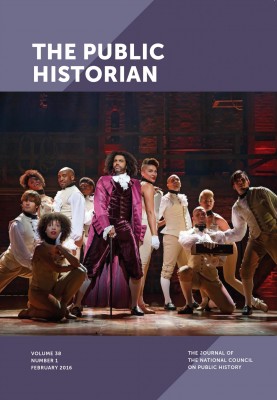

Finally, we are pleased to publish a provocative review of the widely praised Broadway show Hamilton in our pages. Lyra D. Monteiro, while recognizing the many revolutionary and artistic breakthroughs in the production, cautions through fine detail that “the play can . . . be seen as insidiously invested in trumpeting the deeds of wealthy white men, at the expense of everyone else, despite its multiracial casting.”

Taken as a whole, this issue shows that public history harbors the potential to hone the edges of the most incisive historical practice and interpretation today and yet remains subject to deployment in ways that run counter to our progressive mission, which is to promote deeper historical appreciation in the interest of an inclusive civil society. Whereas Miles ultimately found she could only write “endings that may be hopeful for women and other marginalized groups today” through the genre of fiction in her celebrated 2015 novel, The Cherokee Rose, we can hope that the cases illuminated in our essays suggest that at least in some instances, those audiences may also find hope in the fragments of history restored by practitioners. Finally, we hope you will appreciate the fresh redesign of the journal that debuts in this issue–new typography, layout, and cover treatments that bring the “look” of the journal into alignment with the leading-edge nature of its scholarly content.

* * *

This issue also allows me to welcome new members to our Editorial Board. Jeremy Moss, Chief of Science and Resource Stewardship/Archeologist at Pecos National Historical Park, joins us from New Mexico to further our engagement with National Park visitors during its centennial year (and many ahead). Moss, a well-published scientific archeologist, has served at Canyonlands National Park, Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Petroglyphs National Monument, and Saguaro National Park. He has also served as a board member of the Friends of the Santa Cruz River (AZ), the Southwest Mission Research Center (AZ), and as a professional advisor for the Santa Cruz Valley Chapter (Tubac) of the Arizona Archaeological Society.

Moss’s immediate past appointment was as the chief of resource management and park archeologist at Tumacácori National Historical Park, Arizona, in addition to his current posting at Pecos. It was at Tumacácori that I first witnessed his talents as a public speaker and interpreter of the past, on a day in 2011 when he provided the board of directors of the Western National Parks Association a rich tour of the site’s history, as well as fascinating details of the science beneath the construction “recipes” and dates of the adobe walls found there. His skills as publishing scholar, social scientist, and public interpreter will all come to our benefit at TPH in the years ahead.

We also welcome Ann E. McCleary, professor of history at the University of West Georgia, director the Public History and Museum Studies programs, and co-director of the Center for Public History. McCleary has worked in the field of public history for forty years, including museums, public humanities, historic preservation, consulting, and now teaching. Her research interests and publications have focused broadly in cultural history and public history relating to the South, especially Virginia and Georgia. Her specific interests include vernacular architecture, material culture, rural women’s history, traditional music, southern foodways, textile history, public humanities, and museum studies. She holds a PhD in American Civilization from Brown University and a History BA from Occidental College. We are thrilled to expand and strengthen our scholarly and activist representation of the Deep South.

Last but not least, we are looking forward to working with Morgen Young, a consulting historian based in Portland, Oregon. She established her company, Alder, in 2009, after receiving a master’s degree in public history from the University of South Carolina. Her work focuses on exhibit development, oral history, digital history, and historic preservation. In addition, she is a talented photographer who provides stunning images to her clients (see some on her website). Young has worked with museums, universities, medical centers, and other institutions and individuals. She is the co-chair of NCPH’s Consultants Committee, an editor of History@Work’s Consultants Corner, and a former member of the NCPH Board of Directors. Morgen will enhance the board’s expertise in digital history, consulting, and visual culture.

~ James Brooks is editor of The Public Historian and professor of history and anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara.