Navigating the Complexities of Public History in a Changing Legislative Landscape

14 April 2025 – Ian Beamish and Julia Brock

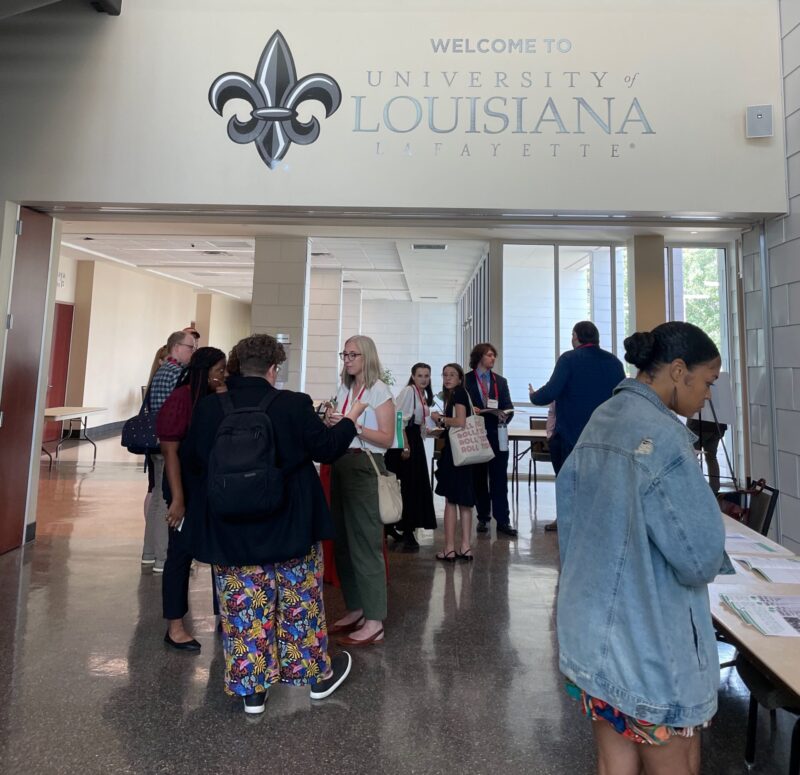

Sixty-five public historians gathered at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette to discuss the state of public history in the U.S. South in October 2024. These historians came from across the South—the Carolinas, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Tennessee—for the NCPH mini-conference co-organized by Ian Beamish, Julia Brock, and Liz Skilton.

Befitting of the gathering’s theme, “Condition Report,” panels and roundtables focused on the current state of practice in the field, situated within increasing attacks on the teaching and circulation of history and scholarship on race, gender, and other topics deemed controversial by Donald Trump and his allies since 2016. Sessions showcased public historians working tenaciously to resist forms of erasure as well as the effects of climate change and other human-driven environmental crises.

Left to right: Conference organizers Drs. Liz Skilton, Ian Beamish and Julia Brock, with NCPH’s Sarah Singh, gather in the lobby of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Student Union. Photo courtesy of Sarah Singh.

As organizers, we scheduled discussion groups at the end of the first day that were modeled loosely on NCPH’s tradition of thematic working groups. We began the “Policy, Law, and Public History in the South” discussion group by sharing links to legislative trackers that documented the anti-DEI, anti-trans, and anti-LGBTQ+ laws and proposals in place and in process at the time of the conference.

Session participants then broke into smaller groups and utilized a set of discussion questions that prompted participants to share their own experiences, observations, concerns, and strategies. Here, we summarize some of what we, as facilitators, heard.

Southern states are not the only places in the country facing policy initiatives that impact public history practitioners and practice (see PEN America’s Index of Educational Gag Orders, the Trans Legislation Tracker, and this open-source list of Disappearing Cultural Org/DEI Websites maintained by NCPH member Jessica BrodeFrank and Kas Tebbetts). As one conference participant noted, the enforcement of laws depends on how deeply a legislative body is entangled in the current culture wars. But many southern states have versions of so-called divisive concepts laws that ban the teaching of precepts such as “the United States is inherently racist” (GA, HB1084) or “individuals, by virtue of race, color, religion, sex, ethnicity or national origin, are inherently responsible for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race, color, sex, ethnicity, or national origin” (AL, SB129). These laws target DEI initiatives and a historical curriculum that has grown more critical and corrective of a received past that traditionally ignored the effects of white supremacy.

It is no coincidence that legislators are pushing these laws in the years following the Black Lives Matter movement and the 2020 uprisings after the police murder of George Floyd. These laws follow in a tradition of white supremacist crackdowns on Black and progressive advocacy in the South, as David Blight and Karen Cox show, with the creation of the Lost Cause narrative and erection of Jim Crow statues to Confederates in response to African American Decoration Days and KKK opposition to the Civil Rights Movement.

Many southern states now, too, have laws that ban instruction relating to gender identity and sexual difference in K-12 schools. The Louisiana legislature, for example, prohibits teacher discussions with students “covering the topics of sexual orientation or gender identity in any classroom discussion or instruction in a manner that deviates from state content standards or curricula developed or approved by public school governing authorities” (LA, HB122). These laws align with others that ban gender transitions, for example, for people under 18 (SC, HB4624).

This uneven legislative landscape creates challenges for public history in the U.S. South, from self-censorship, funding, and preservation to digital capacity, partnerships, and advocacy. One museum professional based in South Carolina reported that museum educators at her institution anticipated changing content to address teacher concerns about recent legislation. A representative at a federally managed public site stated that staff were self-censoring and avoiding the phrase “climate change.” Even before recent federal directives, institutions were changing program design to remove connotations of DEI: one participant’s organization even changed its mission statement to remove language that might be flagged by lawmakers.

Participants gather at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette for the Condition Report mini-conference in October 2024. Photo courtesy of Sarah Singh.

Many participants emphasized that the practices and commitments that inspired DEI have not changed, but verbiage has. Others indicated that they had not yet felt pressure from new legislation, pointing to the particular political negotiations of each state legislature. One participant from a southern HBCU noted that their institution had avoided some of the scrutiny other universities faced because of the state’s long history of neglecting their school.

The conversation was not a collective wringing of hands; in fact, we quickly moved to strategies of resistance and support. One participant suggested looking at the historical role of alternative educational models, like Freedom Schools during the Civil Rights Movement, as a rehearsal for today’s censorship. Another suggested exploring how independent, community-led archival projects can circumvent state control and preserve marginalized histories. Several echoed the need to be in close contact with funding agencies, both public and private, to make them more aware of the needs of public historians who are operating in states with adverse legislation. One participant reminded the group that artists, whose work may not be dictated by institutional constraints, can be key collaborators in creating powerfully resonant historical narratives.

Overall, the tone of the discussion melded exhaustion and determination. Many public historians underscored the degree to which they were feeling burned out after years of advocacy at the local, state, and federal levels. Others highlighted that progressive historians have long faced enmity, and that they remain determined to fight for public history. Even those reeling from the effects of long-term, sustained advocacy expressed their commitment to the cause.

While the work is challenging, participants agreed that it makes the vitality of public history even more important. Less than three months after the mini-con, Donald Trump’s second presidential administration began implementing a chaotic and threatening new set of measures that enshrined an attack on DEI and trans people into federal policy.

Regional cooperation and collaboration across state lines will allow public historians to combat these legislative challenges and present compelling narratives in innovative, energizing ways. This mini-con provided an important starting point for this kind of cooperation and collaboration, but it will be important to not lose momentum. We must continue working across (and beyond) the region as attacks on public history work intensify.

~Ian Beamish is an associate professor of public history and director of the Public History Program at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

~Julia Brock is an assistant professor of history at the University of Alabama, where she also coordinates the Public History Concentration. With Evan Faulkenbury, she is co-editor of Teaching Public History (UNC Press, 2023).