New Frameworks for Evaluating Historic Properties

22 September 2023 – Sara Zarrelli and Guy Hermann

Editors’ Note: This essay is by the recipients of the National Council on Public History 2023 Excellence in Consulting Awards-Group Award Honorable Mention. The award was presented to Guy Hermann, Sara Zarrelli, and Jacques Brunswick of Museum Insights for their Connecticut Landmarks Portfolio Assessment.

“The reports of the death of Historic House Museums has been grossly exaggerated.” (With apologies to Mark Twain.) Here, we present a framework for evaluating and managing historic properties that Museum Insights developed for Connecticut Landmarks (CTL), a state-wide, non-profit preservation organization operating multiple house museums. We welcome other organizations to adapt this framework and share with us their challenges and successes.

Nathan Hale Homestead, Coventry CT, courtesy Connecticut Landmarks

The 1966 National Historic Preservation Act and subsequent celebrations of the nation’s bicentennial in 1976 codified public interest in preservation. On a local level, this led to the creation of new house museums, many of which quickly ran up against the challenge of maintaining their properties, as many readers will know first-hand. High maintenance costs have hit large and small organizations alike. Facing these costs, some organizations sold historic properties with preservation easements, others transferred properties to different organizations for stewardship, and still others reprogrammed the space, shifting their focus from exhibits to programs and event space.

Refocusing Properties at Connecticut Landmarks

Since its 1936 founding, CTL has acquired historic homes through bequest and sale, restored and maintained them, and operated them as museums. As their portfolio grew, their operating practices and revenue sources didn’t keep pace. By 2021, with eleven historic buildings and a large material collection, the preservation backlog had grown and CTL couldn’t support the kinds of new programming—including interpretation grounded in the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience model—that it wanted to adopt. To help them assess operations, CTL hired Museum Insights, a firm that helps museums plan for change and develop sustainable business models, to conduct a holistic review of all properties, develop a property assessment tool, and work with the staff and board to create a plan for change.

CTL’s properties include:

Phelps-Hatheway House and Garden, Suffield, CT, courtesy Connecticut Landmarks

- the site of Revolutionary War spy Nathan Hale’s birth;

- the Palmer-Warner House, home of a mid-20th-century gay couple;

- the Bellamy-Ferriday House, built by Great Awakening preacher Joseph Bellamy and home to Caroline Ferriday, philanthropist and humanitarian who inspired the novel The Lilac Girls (2016);

- the Butler-McCook House, where four generations of one family lived, including John J. McCook, who helped lay the foundations for the modern field of social work;

- Phelps-Hatheway House, one of the best examples of late 1700s hand-blocked wallpapers extant as installed by Oliver Phelps, who sold land taken from Indigenous groups;

- the Hempsted Houses, which reveal the story of Adam Jackson as documented by his enslaver, Joshua Hempsted;

- and five other buildings with lower profiles.

The distinct nature of each property made a one-size-fits-all management approach ineffective. To understand each property’s strengths and opportunities for growth, we developed a matrix to document and prioritize desired and potential “mission outcomes” (activities that support CTL’s mission) and “money outcomes” (activities that fund CTL).

We defined seven mission-related criteria:

- Alignment with CTL mission

- Architectural preservation value (architectural significance)

- Historic significance (the people and events that define each property)

- Interpretive potential (the people, events, and stories that interest visitors)

- Community engagement (how the community interacts with the property)

- Collections (associated material culture or manuscripts)

- Potential visitation (considering location, interpretive themes, accessibility, and programming).

And seven money-related criteria:

- Restricted endowments and trusts (many of the properties have restricted funds)

- Admission and program income

- Rental and other earned income

- Contributions/grants

- Occupancy costs

- Net revenue/loss

- Condition (anticipated cost of restoration work needed within the next ten years)

For each of the 14 criteria, we provided a scoring range with examples so that CTL staff and board members were working from the same definitions. We then applied each criteria to each property, and invited individual staff and board members to do the same. There was general agreement from the staff, board, and consultants for both mission and money scoring for all the properties. This confirmed that we were posing the right questions for evaluation.

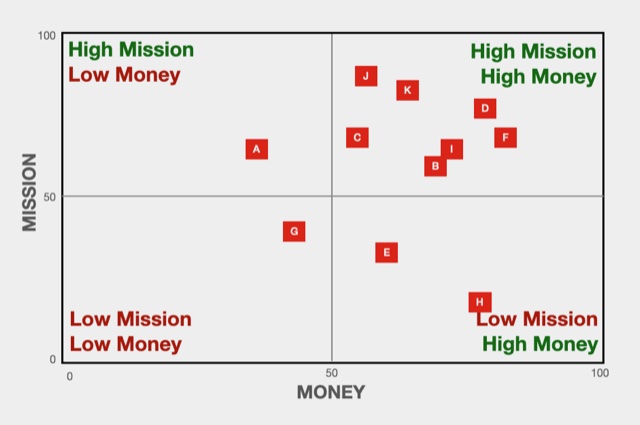

To develop recommendations, we plotted results on a scattergram using mission and money as the two axes, creating four quadrants:

Scattergram showing CTL properties on the axes of mission and money.

High-mission/high-money properties needed few changes, but understanding how to program and value low-mission or low-money properties was more complex. To help generate feasible ideas, we developed three property types:

- Flagship properties are the most active, typically scored as high mission and high money. They draw visitors to experience a wide range of events, tours, and programs related to a high-profile person or topic (Nathan Hale and Bellamy-Ferriday).

- Go Deeper properties are open for special programs and offer opportunities for enrichment for specific interest groups by providing in-depth, participatory explorations (Palmer-Warner and Phelps-Hatheway).

- Serve the Field properties have special qualities that make them worth keeping but are challenging to program and may be most valuable as laboratories for training future preservation professionals.

By classifying each of the properties programmatically as one of these types, we were able to identify a business model for each that has the greatest potential for success.

- Flagship properties will generate earned revenue through admission, programs, and events. They are high visibility and a primary focus of CTL’s marketing efforts.

- Go Deeper properties’ rich and diverse programming will generate community support through memberships, donations, and legacy gifts.

- Serve the Field properties will be a chance for CTL to fully engage with historic preservation. Close attention of the curatorial and preservation staff can inspire grants and legacy gifts.

Of course, there is overlap between these types, but the overall structure gives CTL a method to allocate resources among the properties in ways that benefit both the property and its publics.

Following this work, CTL is moving ahead with a strategic facilitation process. With 85 years of organizational history, the effort to rethink operations is not a simple process, but CTL is now thinking more broadly about its long-term property management. At the same time, CTL is making short-term decisions about budget, program planning, and collections stewardship by prioritizing highly ranked properties. Lower-ranked properties are being evaluated for paths to improvement. Focus is on resource development through federal grants and state funding to offset maintenance costs, recognizing that even high-mission, high-money properties like Hale Homestead still have gaps in their operating budgets. Another example of the organization rethinking interpretive programming is a linseed oil paint workshop at Phelps-Hatheway House. And this is just the beginning. While making change within a historic organization is challenging, we hope that this framework provides new insights to other organizations looking for change.

~Sara Zarrelli is a museum planner and public historian who brings together experience working for historical units of the National Park Service, non-profit organizations like Historic New England and The Trustees of Reservations, and as an independent historian. Her passion is helping historic sites develop a sense of place through exhibits, landscapes, and experiences that meaningfully connect visitors to the messy realities of the past. Email: [email protected]