Preserving Intellectual Disability History: The Elwyn Archives and Museum

31 May 2022 – Chelsea D. Chamberlain and Elliott W. Simon

Elwyn’s band, circa 1890s. Image credit: Elwyn Archives

Founded in 1852 as the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children, Elwyn is the oldest continuously operating educational facility for people with intellectual disabilities in the United States. Today, headquartered just outside Philadelphia, it is a large multi-state provider of community-based and residential supports to people with a wide range of disabilities. Beginning in 2014, Elwyn’s administrators, the Pennhurst Memorial and Preservation Alliance (PMPA), universities, and self-advocates collaborated to process more than 125 linear feet of records related to Elwyn’s long and significant history.

Processing these records made it possible to uncover new stories from Elwyn’s past: in March of 1911, the band staged a rebellion. The boys and young men had spent the year in excited anticipation for the annual elaborate dinner that celebrated the group. When the superintendent, “wishing to reduce expenses,” presented them instead with lemonade and cake, the band took over a practice room and “howled, hooted, screamed, yelled and refused to come out,” declaring they would “stand by their rights” to a full dinner. As a staff member walked them to the building in which they were to be punished with isolation, they bolted, and many escaped the campus. Many more such stories reside in the recently developed archive and historical museum at Elwyn. The Elwyn archive offers access to rich, extensive collections that reveal not only the diverse ideologies and experiences of psycho-medical experts, teachers, and charity workers, but also those of institutional residents and their families.

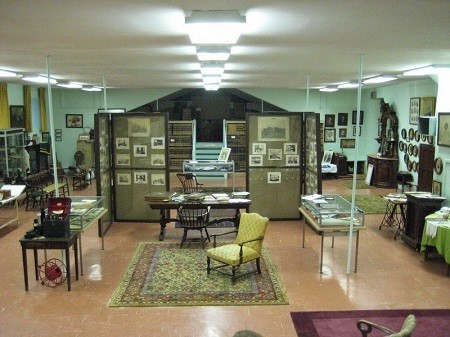

Elwyn Museum and Archives. Image credit: Elwyn Institute

After the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s Hidden Collections Initiative for Pennsylvania Small Archival Repositories created an initial finding aid, a steering group with members from Elwyn, the PMPA, local universities, and self-advocates began processing the large collection. Elwyn’s supported employment program and the self-advocacy group Speaking For Ourselves recruited project staff with intellectual disabilities who worked alongside interns from West Chester University and Millersville University to inventory and organize the collection. Though preservation was the primary goal of the project, it also incorporated public education and advocacy through presentations at local historical societies, conference panels, and a conference at Elwyn when the archives were rededicated.

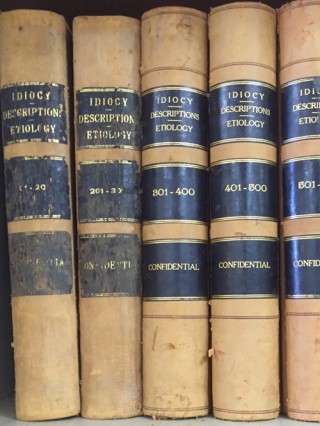

Bound pre-admission volumes, 1870s-1880s. Photo credit: Elliott W. Simon

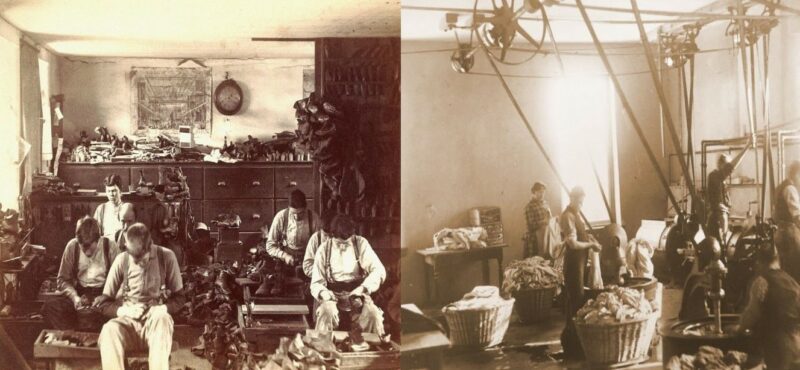

Many of the early records within Elwyn’s archive reflect a medicalized approach to disability. Physical examination records, medical records, and clinical photographs place people under the physician’s gaze and attempt to reduce them to measurements. Records such as these are valuable for scholars seeking to understand the social construction of disability because they demonstrate which measurements and physical characteristics were considered crucial indicators of impairment and which were not. More powerfully, Elwyn’s archive contains sources that provide a rare opportunity to understand the lives, choices, struggles, and victories of residents and their families. Outgoing correspondence, which reflect the grief or relief that families experienced after placing kin in an institution, document the ongoing negotiations between families and superintendents over proper diagnosis, care, and discharge. Pre-admission forms—lengthy surveys about an applicant’s personal and family history (see accompanying photograph)—were often filled out by families, charity societies, or physicians. These provide wide-ranging perspectives on the alleged causes and curability of perceived feeblemindedness. Medical and school records document the daily tensions between institutional staff and the residents who challenged them. Hundreds of photographs reveal the daily routines of the people who lived at Elwyn. These routines included unpaid labor such as making shoes and working in the laundry room.

Elwyn’s cobbler shop and laundry room, circa 1880s. Photographs like these offer a glimpse of daily life and labor for Elwyn’s residents throughout the institution’s history. Image credit: Elwyn Archive

Housing these collections within service providers such as Elwyn—with their own budgetary, legal, and healthcare priorities—can make them more difficult to access than those held by formal archives. Unlike a public archive, as a private, healthcare-oriented organization, Elwyn is bound by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), a federal law that protects access to a person’s health care information. Given HIPAA constraints, researchers must use pseudonyms for individuals who have been deceased for less than 50 years. Unfortunately, this can perpetuate historic injustices: residents go nameless while superintendents do not. Elwyn plans to hire a staff person to oversee its holdings as part of a long-term campus reorganization while developing an organization-wide historic preservation plan. Ongoing collaboration with outside scholars, activists, and funders will be required to make this archive, and the moving stories that it contains, more readily available to researchers. For more information on the Elwyn archive, contact Pamela Danner, Executive Director, Strategic Projects.

~Chelsea D. Chamberlain is an assistant professor of History at Wilkes University. She received a PhD in history from the University of Pennsylvania and a MA in history from the University of Montana. Her research focuses on the education and institutionalization of children deemed feebleminded in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century United States.

~Elliott W. Simon is a PMPA board member and its director of government relations. He is a licensed psychologist with more than 40 years of experience as a clinician, researcher, and administrator in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities. A graduate of Emory University with a PhD in psychology, he is the past executive director of research and quality improvement at Elwyn and served as the curator of its archives and museum.