Public history in the classroom

22 February 2017 – Elizabeth Belanger

Sharing Stories: College students and teens dialoging at the community center.” Photo credit: Elizabeth Belanger

Over the past weeks my project colleagues have provided glimpses into public history’s “Radical Roots.” In these posts, key figures and sites have emerged: Gene Weltfish at the American Civilization Institute of Morristown, the campers and counselors at Camp Woodland , and Louis Jones at Cooperstown Graduate Program. As these blog posts attest, radical public historians as early as the Progressive Era have sought out untold stories and voices, and worked in deeply local contexts. My own work explores how we can see the tendrils of public history’s radical past influencing its current practices.

With eight years of teaching under my belt and previous experience teaching an undergraduate public history practicum course, I entered into my current collaboration with a sense of confidence about how I could help my students navigate the complicated and often frustrating circumstances of community partnerships. “You need to be flexible,” I would caution my students. “You can’t expect community partners to conform to the academic calendar.” “You need to listen, and to respect community knowledge and expertise.” Above all, I reminded them, “You need to undertake this project with them, not for them.” The values of reciprocity, respect, and understanding were echoed in the social justice-oriented model projects we examined and the readings we did in the class. But as we worked to place reciprocity, respect, and understanding at the center of their interactions with community members, I found myself rethinking what it meant to teach a “successful” radical public history practicum course and what a “successful” radical student project looked like.

Brainstorming at the community center. Photo credit: Elizabeth Belanger

I work at a small, liberal arts college in western New York. Our collaboration with the community emerged from conversations with the director of an afterschool program for teens in the city. The teen center had a vibrant arts curriculum and we brainstormed ways in which we could integrate public history into an arts project for the city’s monthly celebration of arts and culture. What emerged was a ten-week collaboration where students from my course, “Art, Memory and the Power of Place,” and teen artists would craft a public humanities project.

The theoretical framework for the course came from the writings of both art critics and historians who talk about dialogical projects. As John Kuo Wei Tchen, one of the founders of the Museum of Chinese in America (formerly known as the Chinatown History Museum) notes, “to be dialogue-driven is a work process where documentation, meaning, and re-presentation are acknowledged to be co-developed with those whom the history is of, for, and about.”[1] As I started to craft my course, I discovered it was relatively easy to find evidence of public history work that shared similar values to the ones I wanted to encourage my students to adopt. Recent work like the Guantánamo Public Memory Project includes sections of the exhibit where exhibit authors articulated their personal viewpoints and stories. But for the most part, however, descriptions and reviews of final public history projects did not include descriptions of their classroom procedures. I found little evidence of how project collaborators built bonds of mutual respect and trust central to dialogical work. In addition, I found myself struggling to assess such values. How do you grade community interactions? Can you assume that these values are reflected in the end work? Is it possible to have a process that reflects meaningful collaboration and an end project that does not?

As my collaborator Rachel Donaldson notes in her post, despite an existing historiography which focuses on public history’s ties to traditional academic history, public history is, and has always been, interdisciplinary. Yet for the most part, we tend to assess public history projects using traditional assessment measures. The Public Historian advises reviewers to explore the “work’s significance for public historians,” “how it fits within a body of scholarship,” and to “critically engage with the issues of the exhibition” in their reviews. A quick survey of on-line syllabi reveals public history student projects that are assessed on their historical accuracy, objective analysis which incorporates multiple viewpoints, and their overall “argument.” Teaching radical history requires us to rethink these notions of success.

In framing my course’s public history work as “with” the community and not “for” them, I turned to crafting course assessments which privileged processes over the product. A weekly reflective journal where students were asked to document and reflect on the process of undertaking a public humanities project served as the main assessment of student learning. The journal format, adopted from Dr. Edward Zlotkowski’s service learning model, was designed to facilitate deep reflection on the collaboration—asking students not only to record what happened, but to examine how their own biases and assumptions shaped their work. The journals were also exercises in listing and observation. Students had to recount specific interactions with their collaborators, exploring how social identities, and issues of power, authority and voice were evidenced in their relationships with others.

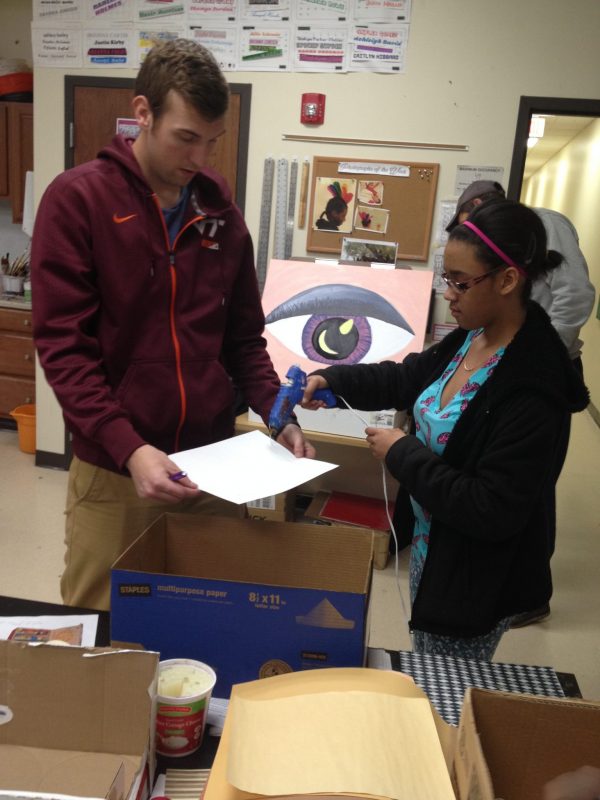

Teen and college student collaboration in the Arts Room. Photo credit: Elizabeth Belanger

When it came to assessing the final project, I turned to the students and teens themselves. “What,” I asked them, “will make this project successful?” What I found most interesting about their responses was their disregard for elements some historians might use to define “success” and rather, their embrace of the affective dimensions of the work. In their reflections and journals they clearly communicated how they had been personally transformed by the work, and how they hoped the work would transform viewers. It was a definition of success rooted in changing the hearts of their audience, not their minds.

College Collaborator: “I would rather be judged on the personal impact rather than the art itself. If it affects peoples, their emotions, they are inspired and it makes them happy—then that is successful.”

College Collaborator: “It will be successful if the people in the project feel that they had a voice [in the project] and were able to speak to community members through a different venue.”

Teen Collaborator: “I’ll be happy if it makes one person think. If they keep it with them while they are living. I mean it would be great if the whole community was affected, but I know for a fact that is probably not going to happen. It will probably make some people think for a little while then go away.”

Ultimately, the affective perspective my students brought to their radical public history work got me thinking that perhaps we need to look more closely at where our students are coming from and why they are choosing to take public history courses. Certainly some students enroll in public history courses because, as many department websites highlight, it provides them with job training, and teaches “hands-on” skills, including collaboration and project development, but for my students, undergraduates in a liberal arts setting, a public history practicum made evident their desire to learn more about themselves (their assumptions and biases) and to work with different groups of people. Thus a “successful” project was a project that pushed both its creators and audience to re-imagine their place in the world. As public humanities scholar Julie Ellison notes of her research on graduate students in the public humanities “we must take to heart the growing evidence that the desire to become a different kind of person is driving change in the humanities.”[2] While assessing “soft skills” like dialogue, critical reflection, and collaboration is difficult, doing so sends a message to our students that our course assessment aligns with the values we purport to teach in radical public history. If we want to educate the next generation of radical public historians, we need to not only be the change, we need to teach it.

~Elizabeth Belanger is an associate professor of American Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York. Her work has been published in the Journal of American History, The History Teacher, The Public Historian, and Arts and Humanities in Higher Education. She is currently the director of the People’s History of Geneva, a community oral history project which is working with the Geneva City School to create a local history curriculum.

1 John Kuo Wei Tchen and Liz Ševčenko, “The ‘Dialogic Museum’ Revised: A Collaborative Reflection,” in Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World, edited by Bill Adair, Benjamin Filene, and Laura Koloski (Philadelphia: Pew Center for the Arts, 2011), 82.

2 Julie Ellison, “The New Public Humanists,” PMLA 128, no. 2 (2013), 296.