Roads Not Taken: record-making in historical perspective

24 November 2020 – Alea Henle

collections management, archives, material culture, Digital humanities, collections, historical societies, research

In 1814, philanthropist Isaiah Thomas (1749-1831) spearheaded the establishment of the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, MA. One of his earliest actions, as president and librarian, was to create and maintain the society’s records. He dedicated a volume to documenting gifts, and decided what information to include in the records, for the sake of posterity. But what details matter, historically and today? From the vantage point of two centuries later, I both appreciate and regret the determinations he and his successors made. The decisions of past generations in creating institutional records offer insights and lessons for creators of twenty-first century digital humanities projects. [1]

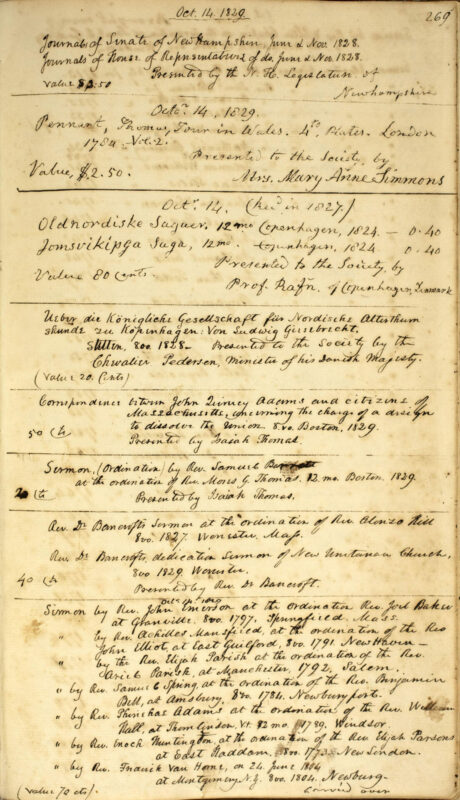

Accessions recorded by Isaiah Thomas and Christopher Columbus Baldwin, October 1829. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Thomas did not develop the American Antiquarian Society institutional records in a vacuum. Prior to retirement, he spent years working as a printer and bookseller and overseeing a growing business. Moreover, Thomas drew on Euro-American traditions of learned societies and record-keeping. In Great Britain, the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries of London obtained charters, took meeting minutes, and maintained correspondence and donation records, as did the closer-to-home example of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and Massachusetts Historical Society, both founded in Boston in, respectively, 1780 and 1791.

in recording the first donations, Thomas valued a degree of specificity—who from where gave what, when, and of what value.

Who and where: the donors, so that they might be properly acknowledged.

When: the date of the gift.

What: the materials that they contributed, most detailed so as to be individually identifiable.

In the case of large donations, such as Thomas’s own gift of “All the Books, &c. . . . [in] one part of [his] private Library,” he provided a brief summation and produced separate indexes noting individual volumes. Last but not least, Thomas included an assessment of gifts’ monetary worth. He estimated the portion of his private library at $4,000; to place this in context, Thomas valued the three large, leather-bound books he purchased and donated for record keeping, including the volume in which he noted donations, as worth $8.50. For trickier items, such as family heirlooms and manuscripts, he did not include valuations. Yet the mere fact he did so for some sets them apart; assignment of monetary value reflected assurance of the existence of a market for the items. [2]

Simple enough, and similar to what modern institutions record when accessioning items. Most equivalent societies—such as the historical societies of Massachusetts and New Hampshire—did not match Thomas’s level of detail at the time. They documented early gifts, but with varying degrees of attention and occasionally omitted important information such as the donation year. In contrast, Charles Hosmer (1785-1871), recording secretary of the Connecticut Historical Society (founded in Hartford in 1825 or 1826, and then re-established in 1839) maintained a careful accounting of all that the Connecticut society received, down to and including a gift involving a very large bean pod. Likewise, officers in Maine, Maryland, and Pennsylvania noted gifts with attention to who, where, what, and when—but not monetary value. [3]

The American Antiquarian Society archives were one of the first I worked with, as I examined how early historical societies shaped the materials available for modern historians to write the history of peoples in the Americas. Perhaps the Society’s archives spoiled me, setting up unrealistic expectations for well-arranged organizational records containing detailed notes describing donations item-by-item, with monetary values assigned two-thirds of the time. On the other hand, the Society’s early records reveal the problems early officers faced in developing and managing historical collections. All researchers face similar difficulties in reviewing historical records while gathering materials, as do modern historians, librarians, archivists, curators, and others involved in managing collections and developing programming.

What details matter?

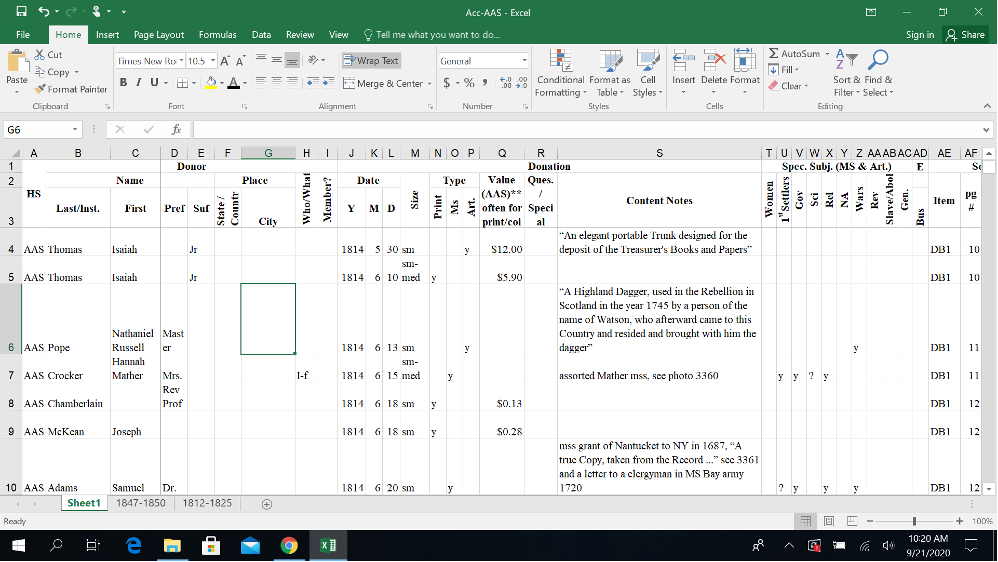

In working with historical society accession records, I created spreadsheets for each society—each slightly different. My recordkeeping variations arose from the differences in the records I worked with. It took me longer than I like to admit to realize I didn’t need a column for monetary value for any society other than the American Antiquarian. The deviations between spreadsheets reflected increasing awareness about what information I found to be of most historical use and how I expected to analyze the data.

Developers of digitization projects invest extensive time establishing possibilities and limits at the outset. Certain tasks are best done before the bulk of coding. Key elements of successful design include accurately identifying what information one wants to collect; how to break it down into pieces (for example, a single field for names versus separate fields for first and last names versus additional fields for prefixes, suffixes, and presumed gender . . .); which fields should be fixed or variable; and the relationships between types of data. Once a given project is underway there are rarely opportunities (or money!) to make changes.

I collected data for personal use in historical analysis and was willing to juggle multiple spreadsheets. As a result, no one but me had to tolerate the data’s limitations.

The same is not true of most historical databases, digitization initiatives, and other digital projects. Decisions made months, years, and decades ago constrain the ability of any given project to intersect with others or be built upon by succeeding generations.

Such proved true of the American Antiquarian Society’s donation records. Thomas’s successors struggled with his model. The next full-time librarian, Christopher Columbus Baldwin (1800-1835), focused attention upon growing the collections and preparing a catalog of the books. His replacement, Samuel Foster Haven (1806-1881), found Thomas’s arrangement of the donations insufficient for his purposes. Over the late 1830s and early 1840s, Haven attempted to document and arrange gifts by subject, i.e. make donation records supplement the Society’s new catalog. By the late 1840s, he gave up and returned to accession records resembling Thomas’s—but without monetary valuations. [4]

I haven’t done much with Thomas’s assessments yet; my project went in other directions. Nevertheless, his valuations remind me of the importance of forward-looking thinking in record-making, particularly during design phases. They also remind me of the importance of considering what information to make available—or indexed or searchable—for accessing and analyzing historical resources. Thomas could create his accession records without thought for other institutions. But in a digital world, interconnectivity is worth its weight in virtual gold.

~Alea Henle is an Associate Librarian and Head of the Access & Borrow Department at Miami University (Ohio). This essay reflects upon research for her recent book Rescued from Oblivion: Historical Cultures in the Early United States (University of Massachusetts Press, 2020).

[1] “Donations to the American Antiquarian Society with the Names of its Benefactors,” March 1813-October 15, 1829, Folio vol. 17.1, American Antiquarian Society Archives, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass.

[2] Ibid, [1]; Thomas also prepared a listing of his acquisition of volumes associated with early Massachusetts ministers Richard, Increase, Cotton, and Samuel Mather. He obtained these through a partial purchase/partial donation negotiated with Samuel’s daughter Hannah Mather Crocker.

[3] “Donation Book,” New Hampshire Historical Society Records, New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord, N.H.; “Library Donations,” [1792], 1812-1813, 1830-1857, folders 1-3, series IIIa, Massachusetts Historical Society Archives, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Mass; “Diaries,” 1791-1793, A.1.11 and B.3.27 and 1794-1798, A.1.12, Jeremy Belknap Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Mass; for Massachusetts Historical Society donations prior to 1850, see also volumes of Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society and Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society; “Accessions,” 1839-1853, Connecticut Historical Society Archives, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Conn.; “Catalog of Books, Pamphlets, Manuscripts, Maps, Belonging to the Library of the Maine Historical Society,” 1822-1872, and “Catalogue of Articles Belonging to the Cabinet of the Maine Historical Society,” Maine Historical Society Archives, (Feb. 1822) Nos. 1-53 + 1863-July 1909, Maine Historical Society, Portland, Me.; “Donations to the Library of the Maryland Historical Society,” 1844-1896, and “Donations to the Cabinet of the Maryland Historical Society,” 1844-1913, Maryland Historical Society Archives, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, Md.; “Library Accession Book I,” 1825-1862, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Archives, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Penn.

[4] “Donations,” July 1, 1830-December, 1839, Folio vol. 17.2; “Accessions,” May, 1840-October, 1851, Folio vol. 17.3; and “Accessions,” October, 1847-May 6, 1859, March 12, 1865-October 14, 1882, Oversize vol. 17.1, American Antiquarian Society Archives, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass.