Repatriation and the work of decolonization

18 June 2019 – Chip Colwell

2019 annual meeting, Indigenous People, museums, NCPH 2019 Awards, conference, American Indians, finance, decolonization, artifacts

Editors’ Note: This is the third in a series of reflective posts written by winners of awards given out at the NCPH 2019 annual meeting in Hartford, Connecticut. Chip Colwell received the NCPH Book Award for Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America’s Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Richard Tallbull, a Cheyenne elder, works with Denver Museum of Nature & Science curator Joyce Herold in the early 1970s to develop a Cheyenne diorama. Photo credit: Denver Museum of Nature & Science

In 1978, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science—where I have served as the Curator of Anthropology since 2007—completed its new hall on Native American history and culture. The museum was proud of its accomplishment.[1] It had spent a decade building the exhibition, which presented hundreds of artifacts that spoke to Native America’s relationship to its environment and explored how cultures survived in places as diverse as the Arctic and Sonoran Desert. The museum had been among the first to include an advisory council of Native Americans.[2] It opened with the blessing of a medicine man. Among the first exhibits on contemporary society was one dedicated to the urban experience of Native Americans, presented through the lens (literally) of a Native American photographer. Soon enough a public panel would tackle contemporary Native American legal rights.

In many ways, the Denver Museum was poised to be a leader in the coming movement that would demand that museums not merely reflect Native American cultures but integrate Native American viewpoints and values. And yet, over the decades, instead of leading the way, the museum fell far behind. This is a lesson in how difficult it is to turn museums, however well-intentioned, into spaces for decolonization.

A close look at the 1978 exhibit could have revealed small cracks in the façade of Native inclusion. The advisory council was made up almost entirely of local Native American leaders who could speak to their urban experience but not always as well to the traditional cultures the exhibit focused on. These leaders represented different nations and tribes; however, since they joined the advisory council because they were local, the leaders did not reflect the many communities included in the exhibition. The exhibit hall itself was called “Crane Hall,” a name that would stick for the institution over the years—the name a reflection of the museum’s willingness to celebrate its Anglo donors, Mary and Francis Crane, over the exhibit’s primary subject. The medicine man who gave a blessing at the opening was largely deployed to fend off claims made by tribal officials demanding the return of sacred objects.[3]

The cracks turned to fault lines in the coming decades. The museum abandoned its programing focused on pressing contemporary issues. Native Americans were invited into the museum, but mostly to sell arts and crafts. The advisory committee largely became honorary, their work eventually whittled down to one evening event each year called the Buffalo Feast. Repatriation claims went ignored. “Crane Hall” became a place focused on Native Americans in the past.

This characterization is not meant to pick on the Denver Museum. It was merely like most of its peers. From the late nineteenth century through the end of the twentieth century, most natural history and art museums in the United States did not take seriously the rights, viewpoints, or values of contemporary Native Americans. These museums had amassed huge collections of artifacts and huge amounts of money to create exhibits. They believed that it was their right, if not their duty, to share the story of Native Americans. After all, they felt they had the expertise to do so.

Starting in the 1960s, though, Native American activists and their allies began to call out the cracks—in many places giant fissures—and ask that they be repaired. They wanted a voice in exhibits. They wanted their ancestors’ bodies reburied. They wanted their sacred objects put back into ceremony. They wanted more curators and historians and archaeologists to be Native American. They wanted not just to be researched but to be respected.

Most museums were then, at base, colonial endeavors.[4] They took resources that were not their own and, largely through force and coercion, made them their own. Even those museum professionals with the best of intentions inherited the assumptions about property rights and cultural authority embraced by their museums’ founders. Now, Native Americans were asking for museums to change, perhaps like asking a carrot to be a banana. Decolonization became a fancy word to describe a process that museums could undergo to expand the perspectives they portray, to share authority on collections and programs, and to reverse the power dynamics that have historically sanctioned dominant cultural groups, particularly white colonizers.[5]

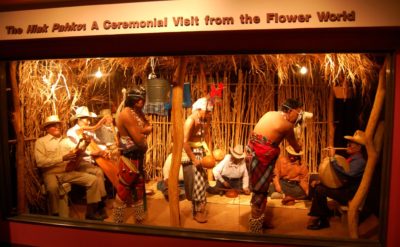

Yaqui diorama at the Arizona State Museum’s “Paths of Life” exhibit, made in close collaboration with the Yaqui tribe and tribal members. Photo credit: JR P

The work wasn’t easy. But a handful of museums took on the task.[6] Today, many people point to the National Museum of the American Indian as a forerunner to the decolonization movement in museums.[7] However, for me, more important pathbreakers include the Arizona State Museum in Tucson and the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, which, in the early 1990s, created exhibits authored by Native peoples in ways that they chose to represent themselves. Also, I’d add to the list Native American communities that created their own museums, such as the Zuni Tribe’s A:shiwi A:wan Museum & Heritage Center.[8]

Entrance to the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture. Photo credit: Ali Eminov

In some ways, there has been amazing progress in the work of decolonization. It’s hard to find a major museum that doesn’t gesture toward the importance of including community voices. Museums in the United States have returned tens of thousands of human skeletons, sacred objects, and funerary objects to the communities that claim them. A few museums, such as San Diego’s Museum of Man, even have a formal decolonization policy.

And yet, what I have seen is that the work of decolonization has hardly begun. In my experience, most museums are like the one I work at: most of their exhibits, programs, and collections are still suffused with colonialist practices. Much of this is built into the flow of time and money. To redo the Denver Museum’s exhibit hall will cost millions of dollars, and the museum has other priorities. But much of this, too, is about how power seduces—how few institutions are willing to surrender control.

There are at least three key measures of how far museums have come—and how far they have to go. First, who directs the money? Second, whose voice drives exhibits, programs, and collections? And third, to whom do the museum’s benefits flow?

In my estimation, today few museums—whether art, history, or natural history—with collections of Indigenous objects share control of resources and voice. They have not yet ensured full and equal benefits with source communities. This is not a reason to give up but a reason to keep going. I have come to see decolonization as a work in progress. A worthy endeavor but one without end.

~ Chip Colwell is Senior Curator of Anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. He is the founding editor-in-chief of the digital magazine SAPIENS, and has written for the New York Times, Atlantic, Foreign Affairs, and many other popular outlets.

[1] Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Steven E. Nash, Steven R. Holen, and Marc N. Levine, “Anthropology: Unearthing the Human Experience,” Denver Museum of Nature & Science Annals, No. 4 (December 2013), 283-335.

[2] JoAllyn Archambault, “Native Communities, Museums and Collaboration,” Practicing Anthropology Vol. 33, No. 2 (Spring 2011), 16-20.

[3] Chip Colwell, Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America’s Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

[4] Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn, eds., Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum (London: Routledge, 1998).

[5] Moira G. Simpson, Making Representations: Museums in the Post-Colonial Era (London: Routledge Press, 1996).

[6] Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

[7] Ira Jacknis, “A New Thing? The National Museum of the American Indian in Historical and Institutional Perspective.” In Amy Lonetree and Amanda J. Cobb, eds., The National Museum of the American Indian: Critical Conversations (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008).

[8] Gwyneira Isaac, Mediating Knowledges: Origins of a Zuni Tribal Museum (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007).