Ride or Die: the “Oregon Trail Live” Q&A

19 November 2020 – John R. Legg

Indigenous People, methods, American Indians, public engagement, decolonization, media, games, memory, sense of place, Q&A, politics, pioneers, LGBTQ history

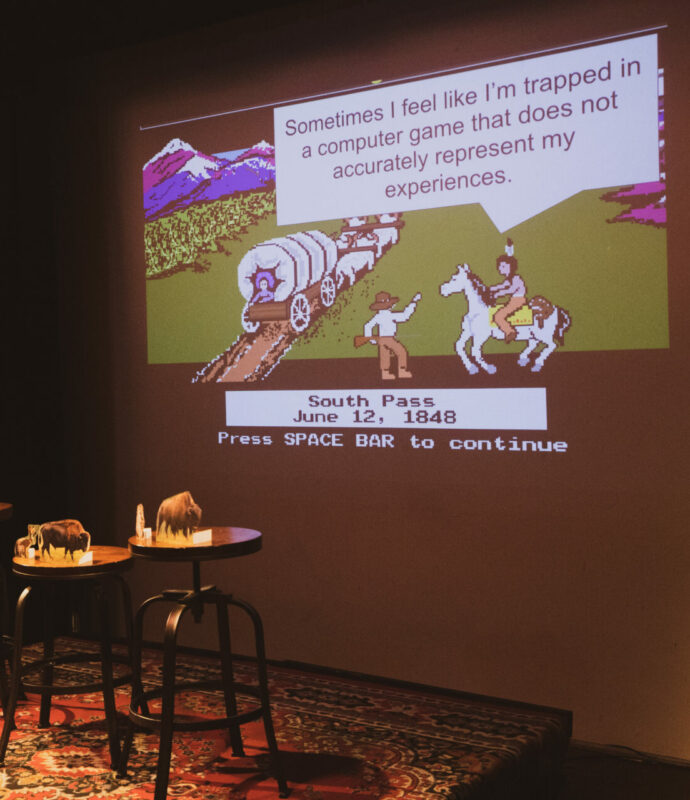

Guests at Caveat in New York City enjoy the immersive Oregon Trail Live event. Photo credit: Arin Sang-urai.

Editor’s Note: Today we welcome Michael Salgarolo and Kylie Holloway to discuss their Oregon Trail immersive game that brought history and leisure together as a way to experience the US West and challenge the colonial foundations of the famous video game. History@Work affiliate editor John R. Legg conducted the interview.

Welcome, Kylie and Michael. Your project, Oregon Trail Live, seems like an exciting opportunity for people to experience history in new ways. Could you briefly tell us about the project and its goals? Also, how did both of you perceive and organize the project?

Kylie Holloway (KH): Hi there! Thank you so much for your interest in our project. We’re excited to tell you about it.

The project started out as an interactive comedy show in a speakeasy called Caveat in New York City. I had been asked to pitch a few ideas for shows to the folks who were running the venue at the time. Like most Americans born in the 90s, I had played the Oregon Trail computer game growing up and knew that a live version of the game combined with a bar setting would likely be a hit. The interactive, high energy format was also refreshingly different from the other, more traditional, stand-up style shows I was making at the time. Also, I’m generally excited about projects that upend traditional looks at history and thought that the drinking game format of the live show would allow us to play with offering new perspectives on trail history with a degree of levity that you don’t get anywhere else. Debauchery is a great place to introduce a little subversion. We got to talk about queer folks on the trail, sex workers, women, Native stories, and white men who screwed up. And our audience of tipsy, young New Yorkers was happy to listen.

I came up with the concept and reached out to Michael, a comedian and historian I had seen at an open mic, about getting on board. Luckily for me, he was game to both co-host the show and partner on developing the show concept. In the two-ish years since we started, we’ve synthesized our show mission and started thinking beyond that basement bar. We are both fascinated by the way our country’s history is told, particularly stories that are as central to American identity and ethos as the Oregon Trail. We have really honed in on the show’s mission to offer up that more complete picture and highlight the stories that we think should be heard. Our blue-sky dreaming, big picture goal is to put those stories into a book about trail history that is contemporary, fresh, and a little bit funny.

It’s great that you’ve been able to weave together so many different stories into the live action version of the game. I wonder if you could give a brief synopsis of the game and the process of playing it in the bar setting?

Michael Salgarolo (MS): Each table at the bar is given a family name, a set of supplies, and ten paper wagon members. The game is a series of challenges that require either skill, knowledge, or good luck. If you’re successful in the challenges, you keep your wagon members. If you’re not, they die. The wagon with the most people alive at the end is the winner.

Challenges include things like “caulk the wagon and float it,” in which teams have to build a “raft” that can keep a miniature wagon afloat in a tub of water. Some groups are given popsicle sticks, some have toothpicks, and some have to make a raft out of matches. If our miniature wagon can stay afloat on your raft, you keep all your wagon members. If it sinks, three of your wagon members die! It’s fascinating to watch grown adults get hyper-competitive over something that is so objectively silly. It gets very intense. We’ve seen many first dates crash and burn. Between the challenges, we do short presentations where we get into the history of the trail.

How do the players of the games seem to react to histories that go against the grain of standard Oregon Trail or American history?

MS: I was nervous about this, since Americans often react poorly when confronted with the uglier truths of our history. Nevertheless, people have been really receptive to the stories and perspectives that we’re bringing to the table.

I often, for example, discuss the work of Elizabeth LaPensée, an Anishinaabeg scholar and artist who sells an Oregon Trail parody t-shirt. It features the classic pixelated image of an ox-drawn wagon, but instead of “you have died of dysentery,” it says “you have died of colonization.” I also talk about When Rivers Were Trails, the computer game designed by LaPensée and a team of Indigenous developers that uses an Oregon Trail-style role-playing game format to tell the story of Native peoples in the era of allotment in the 1890s. Our audience is often pretty moved when hearing about this work, and I think it allows them to think critically about the overland trails and the way that they’re taught in our history books. Several teachers have told us that they’ve since incorporated When Rivers Were Trails into their classroom. But my favorite reaction came when I was talking about how Oregon Trail emigrants were colonizers, and a woman in the crowd yelled out, “WASICUS!” [Lakota slang for “white people.”]

The creators added their own interpretation into the video game, addressing the lack of representation for Indigenous communities. Photo credit: Arin Sang-urai.

Do you feel that players in the game had a true interest in history? Or was it a moment where they felt nostalgic for their childhood?

MS: I think it was heavily geared toward nostalgia, and that’s not a bad thing. The connection to the computer game allowed us to bring folks in that might not have had a strong interest in history otherwise. The audience bought in, not because of their intrinsic interest in the material, but because we were presenting something familiar to them in a new and unexpected way.

KH: I think that nostalgia (and the promise of competitive drinking) was the main driver of ticket sales and got people in the door. However, we got a lot of buy-in from the audience because of the nature of the content. I think subversive history is (forgive my language) trendy at the moment. People have had their eyes opened to the fact that history can be presented in a manner that is surprising, engaging, and funny thanks to work like Drunk History. Also, most of our liberal New York City audience is aware of the fact that the history taught in elementary school was not the complete picture and craves more. So when we’d combine those desires and offer stories of queer people like Charley Parkhurst or sex workers like Julie Boulette and “Madame Mustache” in a humorous way, we’d get cheers and whistles—the beer probably helped as well.

This question comes from one of our lead editors here at H@W. How does humor work with public history?

MS: In my experience, there’s an inverse relationship between the amount of freedom you have to say uncomfortable things on stage and the amount of formal authority you present to an audience. Comedians are professional idiots, and for better or worse, people are pretty open to listening to comedians say shocking or uncomfortable things. At one point during the show, I used to say to the audience, “All right, you white devils, are you ready to get back on the Oregon Trail?” It got a big laugh. If I’d said that in a public lecture? Yikes. The more authority you present, the less room you have to play around. The downside of the comedy approach is that, well, you have to be funny. Having to have a punchline every 30 seconds makes it difficult to tackle complex ideas or detailed sets of facts.

While I’m sure many public historians may be suspicious of incorporating comedy into their work, they may want to consider the ways in which they might broadly adopt a comedic sensibility, and the ways in which they are likely already doing this work. In its essence, jokes, much like good histories, are narratives that upend our expectations. Jokes present familiar concepts in new ways, and foreign concepts in familiar ways. In the Oregon Trail show, I often show audiences pictures of “wind wagons,” small wooden wagons with canvas sails that emigrants tried to use to “sail” across the Great Plains. There’s no “joke” to be written here, even a simple description of the odd device is enough to get a rise from a crowd. Primary sources, in their ability to revive the odd, unexpected, and unfamiliar elements of the past, are often the best jokes of all.

Editor’s Note: The creators of “Ride or Die” hope to continue the event when it’s safe to gather someday in the future.

~Kylie Holloway is a performer and live events producer who uses comedy to celebrate the forgotten women of history and artists you should know about. You can catch her as the host of “Nevertheless She Existed,” a comedy podcast unearthing groundbreaking women of yore, or as a tour guide at museums across the country. You can find Kylie on Twitter.

~Michael Salgarolo is a Ph.D. Candidate in History at New York University and a former Big Onion Tour Guide. His expertise on the weird, wide, and often uncomfortable world of nineteenth-century America has been featured on Inverse, Mental Floss, and Buzzfeed News. You can find Michael on Twitter.