Will digital crowdfunding work for your next project?

25 February 2013 – Noah Goodling

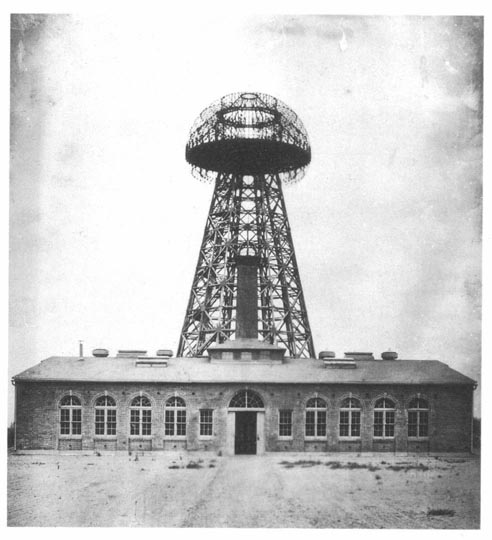

Nikola Tesla’s lab building at Wardenclyffe, 1904

In August, 2012, an extraordinary thing happened: a small museum, dubbed the Friends of Science East (FSE, now the Tesla Science Center at Wardenclyffe), which was being run out of two unused classrooms in a local high school on Long Island, began an online fundraising campaign which raised over $1 million in just over a week. The money was to be used to buy a local historical site, a laboratory utilized by the 19th century inventor Nikola Tesla called Wardenclyffe; the museum planned to repair the site and convert it into a science and technology museum to honor Tesla’s legacy. The story quickly went viral on the Internet, as journalists and bloggers asked the same set of questions: How did a small, virtually unknown museum manage to marshal such incredible resources so quickly? And what implications does this success carry for fundraising for public historians?

The answer to the first question lies in the power of the digital realm to connect together audiences and innovators with shared interests. In this case, the digital tool that was used is called crowdfunding. Crowdfunding is simply a term that is used to describe the backing of projects or causes by groups of people, usually on the Internet, who combine their money and resources to meet a fixed goal. Projects are typically aggregated onto sites that specialize in crowdfunding, like Kickstarter or IndieGoGo.

As mentioned above, FSE launched its crowdfunding campaign with incredible success. Importantly, however, the money did not come in from a handful of mega-donors; statistics from the first week showed that over 20,000 people from 102 countries had contributed an average of only about $40 per person. When I asked about the success of this campaign, Jane Alcorn, the president of FSE, noted several important factors that she felt were crucial to their success:

Internet cartoonist Matthew Inman, aka The Oatmeal, was a key supporter of the Wardenclyffe effort

1) Find the right person or platform to promote your product. Before the crowdfunding campaign began, FSE reached out to popular Internet cartoonist Matthew Inman, who is well known for his impassioned diatribes about the lack of recognition for the contributions of Nikola Tesla to the advancement of modern science and technology. By linking their message and mission with this pre-established fan base, FSE was able to dramatically increase the number of people they could reach and impress with the plans for their museum.

2) Set easily achievable milestone goals. There is a reason this is standard practice in capital campaigns. Although FSE ultimately needed at least $850,000 for the crowdfunding to be successful, the group initially encouraged donators to focus on smaller goals, such as the first hundred thousand, a quarter million, etc. As more milestone goals were met, the campaign inherently appeared to be more successful and legitimate, generating increased enthusiasm and excitement from supporters on the Internet.

3) Take time before the campaign begins to make your cause credible. Before crowdfunding, FSE took time to write a grant to New York State, which assured them matching funds up to $850,000 for any money raised. Having the backing of the state government saved this campaign from needing to defend its reputation or its plans for the museum, making it a viable initiative from the get-go.

4) Use social media aggressively and persistently to promote your cause. Throughout the campaign, FSE used a variety of social media outlets, like Facebook, Reddit, and Twitter, to spread the word, to post updates, to thank contributors, and to increase the transparency of their plans for the site. By reaching large networks of people, FSE quickly and efficiently spread the initial campaign and the ensuing excitement as the funding took off.

Clearly, crowdfunding has enormous potential. Its implications for future fundraising efforts in public history, however, remain to be seen. It would be easy to dismiss the success of FSE as a fluke, a “right-time, right-place” effort that was pushed along by an Internet demagogue. To do that, though, is to disregard a potent tool. It is our goal, as public historians, to connect with our audiences in meaningful ways, and to spur the public to interact with the field of history. To accomplish that aim, crowdfunding presents a system that actively and democratically asks the public to express their support for ideas that are original, interesting, compelling, and practical. In my opinion, those are fair expectations for the future of our field.

~ Noah Goodling is a public history graduate student at IUPUI and the program assistant at NCPH. His BA in History is from Allegheny College. This piece was originally published in the March 2013 NCPH newsletter, which can be found online here.

Nice article Noah! It was a good read.

This is an interesting example of “viral” internet phenomena and social media combining to create exciting outcomes.