“Now let him enforce it”: The long history of the imperial presidency

27 March 2017 – Laura Ellyn Smith

Created in 1832, the year of Jackson’s re-election and his veto of the re-chartering of the Bank of the United States, this cartoon depicts Jackson as a tyrannical monarch, standing on a shredded copy of the Constitution and holding his veto power. It clearly portrays Jackson as overstepping his presidential power. Image credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Historically, imperial presidents have often expanded their power through a crisis that legitimizes their actions. As we look at current events, it is imperative to recognize how President Donald J. Trump is utilizing this tactic. Portrayed as a measure to curb terrorism, President Trump’s efforts to halt entry of migrants from selected predominantly Muslim countries, as well as refugees into the United States, have been identified by political commentators, such as Fareed Zakaria, as fear mongering and religious discrimination. To date, federal courts have blocked the orders and a showdown in the Supreme Court appears likely. Meanwhile, the president has explicitly questioned the power and wisdom of the judiciary, referring, for example, to a “so-called judge” who halted the implementation of the travel ban. The current president’s actions resonate with deep strains in the U.S. presidency, reaching back to the nineteenth century.

Many people tend to associate the term “imperial president,” or the expansive use of executive power, exclusively with twentieth and twenty-first century presidents, and it has been a critical label applied to several recent executives. Over the past few years, for example, some critics argued that President Barack Obama exceeded the executive’s constitutional powers related to immigration with his DACA and DAPA actions, which enabled some undocumented immigrants to remain in the United States and, at least temporarily, avoid deportation.

However, by examining nineteenth century imperial presidents, it is possible to identify examples of executives who created crises in an attempt to legitimize their expansive use of executive power. Especially in our current heated political environment, public history can help people understand more fully the power of the executive office and discern patterns of presidential behavior. Moreover, examining the long history of the imperial presidency enables observers to recognize legal precedents related to the constitutionality of presidential actions and executive power.

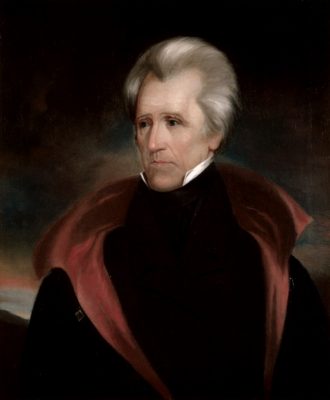

The 2008 documentary, Andrew Jackson: Good, Evil and the Presidency, which aired on PBS, depicted Jackson as the United States’ first imperial president. One of Jackson’s most infamous presidential actions was his enforcement of Native American removal that resulted in the Trail of Tears and the deaths of approximately 4,000 Cherokees. The Trail of Tears occurred despite the Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) that favored the rights of Native Americans. In response to the ruling, Jackson allegedly said, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” Although this statement, which has been repeatedly attributed to Jackson, is likely apocryphal, neither Jackson nor the state of Georgia enforced the ruling. Whether Jackson uttered the famous phrase or not, both Jackson’s contemporary critics and modern historians, such as Daniel Walker Howe, who have studied his presidency have depicted him as a powerful executive who pushed the constitutional boundaries of presidential power.

Beyond the Worcester case, Jackson instigated an additional crisis by portraying the Bank of the United States (BUS) as an enemy of the common man during his re-election campaign in 1832. After being re-elected, Jackson continued his war on the BUS by unilaterally removing funds from the bank and placing them in state banks. For assuming power over Congress, he became the only president who has received congressional censure.

Historian Amy Sturgis fights the myths that plague public perception of Jackson’s presidency. Sturgis sees Jackson as the first imperial president because “Before Abraham Lincoln, he represented selective adherence to the US constitution. Before William McKinley, he represented energetic imperialism. Before Teddy Roosevelt, he represented a cult of personality. And before Bill Clinton, he represented the personal made political.” She describes Native American removal as “ethnic cleansing” and Jackson’s approach to presidential power as “might made right.” Moreover, Sturgis rightly stresses the inaccuracies in Jackson’s battle with the BUS being associated with the perception of Jackson as the champion of the common man. As she explains, Jackson “stepped over his constitutionally given authority in order to fight the national bank” and in so doing his actions, “represented a growth in national government because of the executive power he wielded.” Despite her efforts to challenge popular conceptions of Jackson, however, Sturgis, speaking in 2012, described, “the current love affair that both presidential historians and the popular media seems to have with Andrew Jackson.” Considering the increasing scrutiny Jackson’s legacy has come under in recent years, as apparent in the debate over replacing Jackson as the face of the twenty-dollar bill, public history on Jackson may be increasing public awareness of his controversial actions as president. Nevertheless, it is clear that within our current context, much more public history outreach on the history of the imperial presidency is necessary.

Trump seems to approve of the comparisons that have been made between him and Jackson, as evident in his choice of this portrait of Jackson to overlook his desk in the Oval Office. Image credit: White House Collection, White House Historical Association

President Trump has frequently been compared to Jackson. He even chose a portrait of Jackson to hang in the Oval Office, and recently visited Jackson’s tomb at the Hermitage on the occasion of Jackson’s 250th birthday. In our current political environment, it is unlikely that Trump would be able to refuse to follow a judicial ruling as Jackson did with the Court’s decision in Worcester v. Georgia. Nonetheless, the public and historians alike must remain vigilant and well informed so that we recognize when the president may have exceeded his constitutional powers. Richard Nixon infamously stated that, “Well, when the president does it, that means it is not illegal.” Forty years on, perhaps we can be savvier to presidents with imperial aspirations. Indeed, the job of the public historian may never have been more imperative.

Public historians should encourage more discussion and analysis of the imperial presidency in order to enhance public dialogues about the presidency. Such dialogues are critical as Americans confront pressing constitutional issues, especially regarding immigration and national security.

~ Laura Ellyn Smith is a doctoral student at the University of Mississippi, Arch Dalrymple III Department of History. She gained her MA in U.S. History and Politics from University College London.

This hasn’t aged well.

This is one of the most histrionic pieces I’ve come across in quite some time. That’s a whole lot of energy and fear tied up in imagination regarding Trump. Extra ironic and laughable given the newly installed president’s first 30 days.

Biden has added an exclamation point to presidential imperial action with his rent moratorium in the face of SCOTUS direct ruling an administration had no such universal authority to do so. Biden even admitted it as he did it. The arrogance and lawlessness is stunning.

Just a lovely leftist spin showing this site’s TDS. I was interested in Jackson and Marshall, and got nothing but radical leftist Trump bashing.

Try reading the prize winning biography of John Marshall, written by Albert Beveridge.

ought to be somewhere in most libraries and possibly downloadable from the internet as it is long since entered the public domain.