A different “birthright”: Exploring immigrant history in the birthplace of “America’s Immigrant Problem”

01 January 2019 – Andrew Lang

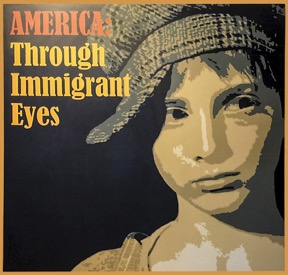

The introductory panel for “America: Through Immigrant Eyes” Image credit: Johnstown Area Heritage Association

In recent years, the debate over immigration and migration to the United States has been especially pronounced, with calls to end “invasions” of “illegal immigrants” from Latin America, build a border wall, institute a “Muslim travel ban,” refuse refugees seeking asylum, and rescind birthright citizenship.

Given this national scope, it has been interesting to see Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where I recently started as curator of the Johnstown Area Heritage Association (JAHA), be prominently featured. In August, David Glosser wrote an article condemning his nephew, Trump advisor Stephen Miller, for his policies that dishonored their family’s experience as Jewish immigrants in Johnstown. And in May 2018, Katherine Benton-Cohen’s Inventing the Immigration Problem was released, shedding light on Johnstown’s role, between 1907 and 1911, as a “test community” for the U.S. Senate’s Dillingham Commission reports on American immigration. Benton-Cohen shows how the reports’ findings were weaponized as a justification for the immigration “quota” laws of 1921 and 1924 that restricted immigration from many parts of the world and have continued to shape immigration policy to this day. She argues Johnstown was “the birthplace of a national consensus on immigration that led to the openly racist quota laws of the 1920s.”

These and other stories have led me to reconsider JAHA’s responsibility to explore how this unique part of the area’s history shaped larger ideas on American identity. If Johnstown is the “birthplace of America’s immigration problem,” then it has a unique opportunity to explore how these current debates are deeply rooted in historical forces, and our local history in particular.

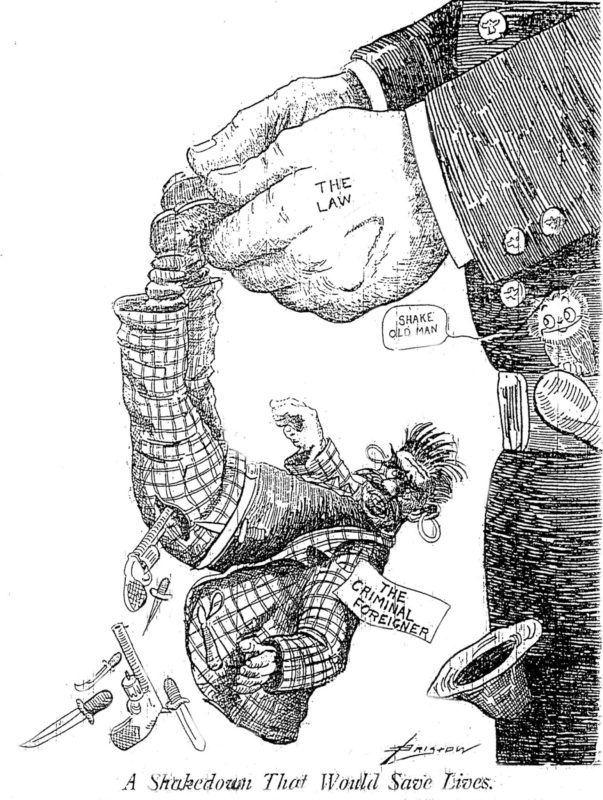

This October 2, 1906 cartoon from the local “Tribune-Democrat” highlights ethnic bashing in Johnstown.

Image credit: Johnstown Area Heritage Association Collections

The immigrant experience factors prominently in JAHA’s exhibition “America: Through Immigrant Eyes,” which opened in 2001. Visitors to the exhibit explore travel to the new world and segregated neighborhoods, experience anti-immigrant sentiment, see the dangerous work of mills and mines, and watch films of Johnstown residents (including Stephen Miller’s grandparents) recounting their immigrant roots.

While the exhibit effectively explores the immigrant experience, there are missed opportunities for other relevant connections to local history. Johnstown’s neighborhoods and mines are primarily used to discuss general immigration themes, leaving many unique elements of Johnstown history unmentioned. There are few artifacts on display, with an emphasis instead on audio and video content created by the exhibit’s developers. And at the end of the exhibit, following a timeline of the twentieth century, there is a single question designed to bring this discussion into the present: “Should America Accept More Immigrants?” to which visitors can answer “yes” or “no.” Though designed to solicit feedback, this question, without a stronger connection to exhibit content or contemporary immigration, threatens to create detached or misrepresented arguments.

In short, there are many areas where a direct engagement with local history could be used to highlight Johnstown’s unique impact on what continue to be contemporary issues. But what would this engagement look like?

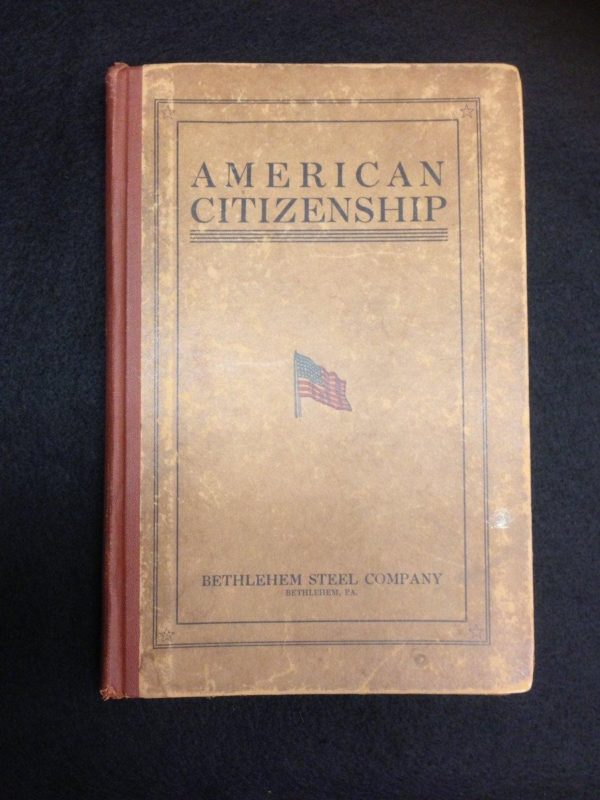

The Bethlehem Steel Company’s 1926 pamphlet “American Citizenship.” Image credit: Johnstown Area Heritage Association Collections

One such opportunity is looking at how material culture can reflect views on American identity. In the museum’s collection is a pamphlet entitled “American Citizenship,” issued in 1926 by the Bethlehem Steel Company (which took control of Johnstown’s Cambria Iron Works in 1923) as a guide for employees seeking to become American citizens. It includes overviews of American government, romanticized narratives of American history, and detailed sections on the necessity of the recent immigration quota system. As one passage reads, “the immigration laws intend that only those aliens who are mentally sound, morally clean, and physically fit shall enter the United States.” I would be interested to see how this pamphlet and other items in our collection might spur further discussion on the idea of who can become an American, and the changing impact of such views over time.

An object such as this one also highlights the connection between Bethlehem Steel and cities such as Johnstown, where population growth was fueled by immigrants migrating to work in these industries. It also raises a key question: what happens when industry, one of the major “pulls” of immigration, leaves an area?

A good example can be seen in the “Becoming American” program at Museum L-A in Lewiston, Maine. The museum paired a film series from City Lore on contemporary immigration stories with public events exploring Lewiston’s immigrant history and the stories of those who came to work in Lewiston’s now abandoned textile mills, helping to highlight similarities, differences, and the validity of these different accounts. At JAHA, such films could be incorporated into existing programs exploring immigrant and ethnic heritage, such as SlavicFest. Moreover, opportunities to bring people together to reflect on their own immigrant experiences across eras and populations must be a strong focus of the museum. Pop-up exhibits, where visitors bring mementos for temporary display, oral histories, forums, and festivals could all be used to create more meaningful connections between past and present immigration narratives.

Representatives of nineteen different countries at the graduation of an Americanization class in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, March 16, 1925. Image credit: Johnstown Area Heritage Association Collections

Finally, JAHA could look to explore stories outside of traditional immigrant narratives that explore migration, identity, and belonging. One little-known consequence of the 1920s “quota” laws in Johnstown took place when local industries began recruiting African-American workers from the South to move to Johnstown and replace a rapidly-diminishing Eastern European labor force. These efforts drove simmering racial tensions that boiled over during the 1923 “Rosedale Incident”: Mayor Joseph Cauffiel, arguing that many of the African-Americans who had recently come to Johnstown had criminal records and could not be trusted, issued an edict banning them from the city. The ban was soon overturned by the Pennsylvania Governor’s office, but not before the majority of Johnstown’s black population left amidst acts of violence perpetrated by the local KKK. Such an event highlights a rallying around fears of migrants that has employed to not insignificant effect in recent years, and thus warrants further exploration.

Topics such as the Rosedale Incident and the Dillingham Commission put the complex legacies of Johnstown’s history in sharp focus. Among many, it is conceivable there would be a resistance to unpacking this. But ultimately, it is not a question of positive or negative history, but rather the ability of a town to address all aspects of local history and recognize its impact. And it is through the small steps in exploring this history—sharing family experiences, mining historical collections, and studying untold histories—that we can better understand our past and counter-inflammatory rhetoric and actions.

No matter how JAHA explores contemporary immigration, it must be done with a strong sense of a local history that shaped and was shaped by immigration history. In Johnstown, arguably the birthplace of larger immigration policy, it is nothing short of our birthright to explore this as meaningfully and completely as we can.

~ Andrew Lang is the curator of the Johnstown Area Heritage Association, which consists of the Johnstown Flood Museum, the Heritage Discovery Center, and other institutions. He graduated from the Cooperstown Graduate Program (SUNY Oneonta) in 2017 with a degree in Museum Studies.

Well written and with a favorable ratio of verbiage to information. Thanks for publishing.

David S. Glosser, Sc.D.

Yardley, PA

I just ran across this article. I was doing a search for the JAHA logo because the child photographed for the museum’s emblematic immigrant is my son Jacob ( who’s now 32). Although his image represents the many Polish immigrant children who worked in coal mines, my son is 3/4 Jewish, with ancestors from Hungary, Lithuania, and Russia.