A response to the election

11 November 2016 – editors

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963. Photo credit: National Archives.

How should public historians respond to the new reality of the incoming political leadership in the United States? Representative democracy in the United States has survived the bitter partisanship of the Early Republic, the Civil War, corruption and scandals, the rise of international fascism, and the paroxysms of protest against the Vietnam War, so it is likely to endure. Historians know well, however, that democratic governance does not always lead to increased justice for all or reflect humane moral principles. History is not unidirectional toward progress, nor is it doomed to repeat itself. Instead, it is the manifestation of the actions of people, including us.

In recent decades, under both Democratic and Republican administrations, we have witnessed mass deportations, human rights violations at home and abroad, and persistent racial and gender inequality. What distinguishes the current moment is the extent to which the president-elect has relished demeaning not only opponents but also some of the most vulnerable members of our society, as well as his willingness to use rhetoric and imagery that is both covertly and overtly racist, sexist, and xenophobic. His campaign was built on a pledge to build a wall on the U.S. border with Mexico and deport all undocumented immigrants from the country. He also discussed temporarily banning all Muslims from entering the country and prohibiting Syrian refugees from entering as well.

Border fence. Photo credit: Steve Hillebrand, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wikimedia Commons.

Whether these pledges will be fulfilled are great threats hanging like the sword of Damocles over our society, especially for those of us who contend that immigrants are a net positive for U.S. society and that providing refuge and asylum to both political and economic migrants is a moral imperative. Under the current administration, the idea that the United States benefits from immigration and the contributions of all immigrants has been under threat as well–despite President Obama’s support for comprehensive immigration reform and continued high levels of immigration. Nevertheless, the president-elect’s proposals would mean an exponential increase in zealous enforcement of immigration laws and the certain breaking up of many more families because of disparities in immigration status and the likely revocation of an order that protects undocumented children.

Moreover, there is a high probability that severe human rights violations and increased vigilante intimidation and violence due to xenophobia and racism will occur. Whatever your political persuasion or opinion on immigration, these outcomes are not ones that any compassionate individual should favor and it is everyone’s moral responsibility to condemn such consequences if they do occur and work to ensure that they do not happen in the first place.

Over and above our individual roles, public historians can and should contribute to these efforts. In the past several decades, our field has worked to foreground stories of marginalized people seeking justice and inclusion, stories that become even more important to share more widely now. Notable examples include the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, Humanities Action Lab, Bracero History Archive, Museum of Tolerance, #museumsrespondtoferguson, and efforts to give voice to enslaved people, women, workers, and others not typically represented at historic sites traditionally devoted to stories of elites. By showing the present moment as part of longer struggles, we can play critical roles in facilitating and leading educational efforts and direct actions to challenge racism, xenophobia, and violence directed toward immigrants or any other vulnerable population. Humanizing immigrants’ experiences and sharing their narratives with broad audiences continues to be essential. At the same time, advocacy around policy and human rights cannot be ignored. Promoting education and dialogue will likely not be enough to ensure that human rights are respected. Public history exhibits and projects provide people with tools to parse how fear and self-interest can be manipulated, but if we want to walk our talk, our institutions will need to continue to strengthen emerging practices of direct engagement and civic action that we see around the field.

In addition to fears regarding racism and xenophobia, many Americans share grave concerns about women’s rights and LGBT rights under the incoming administration. Although it was difficult to identify many concrete policy proposals in these areas from the campaign, the president-elect’s current opposition to abortion rights is clear and the balance of power in the Supreme Court will undoubtedly shift to the right under his administration. For a significant minority of U.S. citizens, this change is welcome and reflects their moral principles in opposition to abortion rights and same-sex marriage. For many others, however, deep concerns about the Court’s continued protection of reproductive rights and expansion of LGBT rights are now at the forefront of their minds. The sea change in public opinion regarding LGBT rights and same-sex marriage under the current president’s administration may mean that marriage equality will endure–although that is far from certain. Reproductive rights, however, face dire threats under a Republican-controlled government and conservative leaning Supreme Court.

Here, again, public history has a role to play. Public historians of all political persuasions share a responsibility to educate broad audiences about the reasons specific protections of reproductive rights came about and the myriad ways in which women have been subject to oppressive social, legal, and medical regimes. See the 2007 issue of The Public Historian on the public and private histories of eugenics for some examples of this work. Because of the deep moral disagreements around this issue, direct advocacy, at least in a professional capacity, may be more difficult here than in the area of immigration.

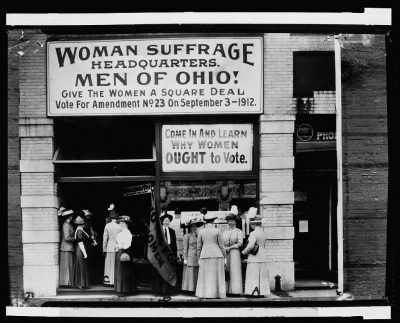

Woman suffrage headquarters in Upper Euclid Avenue, Cleveland. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

However, all public historians can agree that the continued empowerment of women in the face of persistent sexism is a moral imperative, especially in light of the many demeaning remarks the president-elect has made about women. Public historians will have much work to do simply to ensure that a sexist culture does not damage the self-esteem and life prospects of a whole generation of young women. Moreover, public historians should play critical roles in sharing and advocating for strict enforcement of laws and regulations against sexual harassment, discrimination, and assault in our workplaces and the professional and civic communities of which they are a part. The president-elect’s deeply negative model in this area cannot be allowed to stand as representative of our country’s attitudes toward and treatment of women. Moreover, under the rule of law, it must be clear that no individual is above prosecution for crimes that he or she may have committed.

Finally, public historians face a moral imperative to take a stand for freedom of the press and against bullying–both in online environments and in-person interactions. Social media is only the latest outlet for negative, hateful, and destructive rhetoric; newspapers, books, museum exhibits, pamphlets, film, and television have all been platforms to spew venom at fellow human beings. The scale, scope, and immediacy of social media, however, have made it exceptionally dangerous in undermining civil discourse. Yes, it can also be an instrument for organization, protest, community, and empowerment, but its negative fruits are currently outweighing the positives. Is it possible to imagine a Trump presidency coming to pass without the existence of social media? When a bullying personality finds the perfect medium of expression, the foundations of our society can indeed be threatened. Public historians must find ways to combat this bullying culture and encourage all people to value respect and civility above base self-interest.

~ Will Walker is co-lead editor of History@Work. He is an active public historian and author of A Living Exhibition: The Smithsonian and the Transformation of the Universal Museum.

~ Adina Langer is co-lead editor of History@Work and the curator of the Museum of History and Holocaust Education at Kennesaw State University. You can find her on the web at www.artiflection.com and follow her on Twitter @artiflection.

~ Cathy Stanton is a senior lecturer in anthropology at Tufts University and an active public historian. She serves as digital media editor for the National Council on Public History.

~ Modupe Labode is associate professor of history and museum studies and public scholar of African American history and museums at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. She serves as copy editor for History@Work.

“Moreover, there is a high probability that severe human rights violations and increased vigilante intimidation and violence due to xenophobia and racism will occur.” I certainly hope not…but what is that even based off? Evidence or just forecasting based off stupid things Trump has said? Graffiti trolls and keyboard warriors? The only real violence I’ve seen has been by anti-Trump rioters and the thugs that beat up a 50-year-old man b/c he voted for Trump. Was this article supposed to be non-biased appeal to educate the public? The author made some solidpoints, but fell into the trap of cherry-picking to make a point. Tell the whole, ugly, complicated story.

Dear Alexander,

You seemed to have missed the larger point of this essay – that we as public historians have a duty to educate people within our communities about the importance of the past in shaping present conditions; to understand that this year’s election is part of a “longer struggle” to understand the many conflicts and challenges that underlie the basic foundations of the American experience. Educating our many publics about this “long struggle” also requires that we treat others with respect, challenge discrimination, and tell the stories of those who have been and continue to be marginalized within American society.

You might consider the idea that what you believe is mere rhetoric–“stupid things Trump has said”–might be considered by others to be actual threats to themselves and their communities. The “ugly, complicated story” will have to include fact that literally hundreds of incidents have emerged over the past few days throughout the country ranging from Muslim women being assaulted on the streets, to high schoolers calling African American students derogatory names, to swastikas being painted on walls with the text “Make America White Again.” These developments should be a great cause of concern to all of us, including the President-elect himself, who should condemn them immediately. I agree that we should be wary of and condemn any incident in which violence is used, but we should also take the words of our elected leaders seriously and work to educate Americans about the long, historical struggles of the American Experience.

Thanks, Nick. Well said. This report from the Southern Poverty Law Center supports your statement: https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2016/11/11/over-200-incidents-hateful-harassment-and-intimidation-election-day.

Additionally, the incident that you cite of a white man being beaten up by anti-Trump people, seems to have actually been a fight over a car accident, not spurred by the election at all.

http://www.snopes.com/black-mob-beats-white-man-for-voting-trump/

Thank you for reminding us that as historians, we have a continuing role to play educating diverse publics about the realities of our past experiences as a nation – not the “reality show” or talk show imagined versions of what that past was.

I thank NCPH for taking a public stand on the election of Donald Trump as the next president of the United States. Public historians working within the Federal government may need NCPH’s support as time goes on…