A Washington neighborhood uses history to plan its future

09 June 2016 – David Rotenstein

Bloomingdale residents listen to project leaders describe the oral history project, May 21, 2016. Photo credit: David Rotenstein.

Residents of Washington, D.C.’s Bloomingdale neighborhood are using history to plan for the gentrifying area’s future. Through a process of collaborative research and land use planning, they hope to mitigate the adverse effects of displacement, rising housing costs, and the loss of a sense of community. On a rainy Saturday in late May, the Bloomingdale Civic Association (BCA) convened a forum in a former D.C. firehouse to present the results of oral history and documentary research and to unveil conceptual drawings for inclusive neighborhood improvements.

Building on a $2,500 HumanitiesDC grant, the BCA organized a team of resident volunteers who recorded 22 interviews and produced a 35-minute video. Others dug into area archives and memories to create an illustrated timeline [PDF] documenting Bloomingdale’s history. Resident architects and planners gathered input on local land use desires and produced renderings [PDF] for potential new parks, community art projects, and other amenities. Bloomingdale resident Dr. Bertha Holliday, a psychologist, coordinated the study and described the project as one that “combines psychology and design.”

In an interview after the forum, I asked Holliday why it was so important to dig so deeply into Bloomingdale’s history. “We were responding to two recommendations by the Office of Planning,” she replied. “One was strengthening a sense of community and the other one was in terms of strengthening a sense of place. And we thought that by dealing with issues of history and heritage, that was a primary means for strengthening a sense of community identity.”

Bloomingdale Village Square, where old businesses share space with new ones, like yoga studios and cafés. Photo credit: David Rotenstein.

The oral histories drew on the recollections of longtime residents as well as newcomers to the neighborhood. Participants described a tightly knit neighborhood with a rich history. Bloomingdale’s past, like the rest of the District’s, is one of community building and stability punctuated by periods of unrest and crisis. Oral history participants recalled the hours and days following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968. Longtime residents recounted watching neighborhood stores burn as looters ran past carrying their spoils. They then detailed years of disinvestment as abandoned commercial properties failed to attract new tenants. During the 1980s and 1990s, as crack and related street crimes swept through Washington, Bloomingdale’s street corners became retail outlets for the drug as dealers appropriated payphones as their own. One interviewee wondered why the neighborhood had so many crack dealers; afterwards, in the forum discussion, another explained how he used bolt cutters to disable one of the more active phones to get the dealers to move.

Panels on neighborhood history included church and community organization leaders. Participants described their attachments to Washington and to the neighborhood’s history that included Marion Barry’s organizing neighborhood cleanup crews and rallying for the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign march. Local historian Paul Cerruti described how he and Holliday designed the Bloomingdale History Timeline documenting the neighborhood’s story. Cerutti’s activism stems from his interest in the rehabilitation of the nearby McMillan Sand Filtration site, an early twentieth-century industrial facility (water treatment site) and park slated for redevelopment.

Race, economics, and gentrification were common themes in the five-hour program. Local historians underscored the history of racially restrictive covenants that determined where and in what conditions the District’s African Americans could live. Bloomingdale played an important part in the 1948 Supreme Court decision, Shelley v. Kraemer, which ruled racially restrictive covenants unenforceable. One of the cases folded into Shelley v. Kraemer originated in Bloomingdale: Hurd v. Hodge. The historians described increased racial tensions that accompanied white flight and disinvestment. Cerutti described how one entrance to the former McMillan Park was closed and paved over as African Americans began moving closer to the site. Others noted that decades of neighborhood flooding occurred before District officials were pushed to action by new residents with new money and political clout. The end result was the massive First Street Tunnel project, designed to mitigate flooding and relieve the District’s aging stormwater and sewerage infrastructure.

Panelists and participants spoke about the changes sweeping through Bloomingdale over the past decade. Though most agreed that improved aesthetics and attention by District officials were good benefits for all, speculative builders, rising rents and property taxes, and an aging population were contributing to rapid changes in Bloomingdale’s demographics. Some of the changes were attributed to gentrification, others to organic neighborhood succession forces. One audience member was concerned that some of the newcomers weren’t there to support existing institutions; instead, he said that they were there to erode them. He also observed that as the number of liquor stores decreased in recent years, they were replaced by drinking establishments with new issues: intoxicated patrons and parking pressures. These are common complaints heard in gentrifying neighborhoods around the world. The forum found consensus in panelists’ statements that the project’s goal was to develop a stronger sense of community and firmer sense of place to help in managing the neighborhood’s changes.

Bicycle art installation, Rhode Island Avenue NW. The landmark “Bloomingdale” liquor store sign is visible in the background. Photo credit: David Rotenstein.

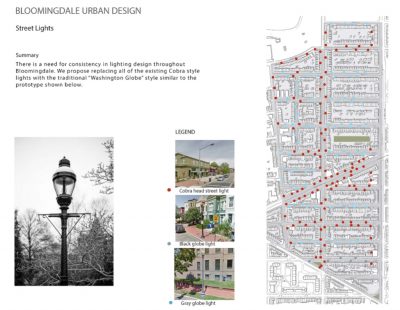

Rebranding Bloomingdale’s commercial core, the intersection of Rhode Island Avenue and First Street NW, as the “Bloomingdale Village Square” was the first step. Visions for the neighborhood’s future include building on existing amenities including parks and art installations. Other ideas featured in the forum included a community-wide mural project, artistic crosswalk treatments, bike rack installations, more environmentally-friendly tree boxes, a community bulletin board, and an ambitious proposal to create parklands in the decks over North Capitol Street. Holliday said that the first two goals were to complete sidewalk improvements (replacing crumbling concrete with brick) and replacing cobra-style streetlights with ones that create a more historic feel. She believes that small achievements will translate into more community buy-in and greater leverage with District government agencies.

Bloomingdale Urban Design: Street Lights rendering. Image credit: Bloomingdale Civic Association.

HumanitiesDC executive director Joy Ford Austin, one of the May forum’s panelists, described the Bloomingdale effort as a model for other District neighborhoods interested in “preserving place and preserving people.” Next steps for Bloomingdale include working with the District’s Office of Planning to incorporate the study’s results into the new cultural plan and to raise more funds for additional interviews, research, and products, like the video and brochures, that will help visitors and newcomers learn about Bloomingdale.

~ David Rotenstein is a consulting historian based in Silver Spring, Maryland. He researches and writes on historic preservation, industrial history, and gentrification.