Leo Frank commemoration: Museum partnerships and controversial topics

17 November 2015 – Anna Tucker

![Leo Frank circa 1910. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-B2-1234]](https://ncph.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/1-218x300.jpg)

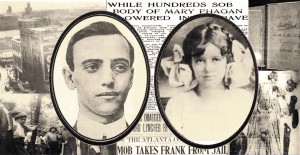

Leo Frank circa 1910. Photo credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-B2-1234]

One hundred years ago and a few miles from the Southern Museum’s current location in suburban Atlanta, a group of armed men lynched Jewish factory owner Leo Frank. Two years prior, in 1913, the state of Georgia sentenced Frank, a recent New York transplant, to death for the murder of Mary Phagan, his 13-year-old factory employee. When Governor John Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence to life in prison in June 1915, the extralegal recourse of prominent members of Mary Phagan’s childhood home sent shock waves through the community that reverberate today. [1]

In the last century, metro Atlanta’s demographics changed considerably, and fewer than 40% of its current residents were born in Georgia.[2] Despite this shift, the aftermath of Leo Frank’s lynching remains controversial in the region. Although “Seeking Justice” presents details of the flawed trial and subsequent lynching, many local residents focus on debating the innocence of Frank while others believe the event “needs to be put away, like the flag, in its proper place.” [3]

Promotional banner for “Seeking Justice: The Leo Frank Case Revisited,” on view at the Southern Museum through November 29. Photo credit: William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum

In response to the simmering controversy, the museum partnership presented five public events to engage the community: a Yizkor (Memorial) Service on the 100th anniversary of Leo Frank’s lynching; a panel dialogue about the Leo Frank case in the media; a tour of “Seeking Justice,” led by the original curator; and two upcoming performances of Alfred Uhry’s Parade in November, with the first, scheduled for this Thursday, featuring a Q&A with the playwright.

Sandy Berman, curator of “Seeking Justice: The Leo Frank Case Revisited,” gives a tour in October 2015. The Breman Museum originally curated “Seeking Justice” in 2008. Photo credit: Southern Museum for Civil War and Locomotive History

Although public history institutions aspire to engage multiple audiences in dialogue, resource constraints often mean they must focus on smaller segments. Through a partnership model, the three primary museums joined together to reach a far wider and more diverse populace. Members of the Breman Museum traveled to the Atlanta suburbs to attend the Southern Museum’s curator tour; a descendant of a lynch party member attended the media panel at the Museum of History and Holocaust Education; and university faculty, homeschool audiences, public officials, and Jewish students attended the interfaith service at Congregation Ner Tamid. While it is unknown how attendance demographics might be different without the partnership, anecdotal sampling suggests that each museum’s affiliation encouraged its core constituency to visit the other museums’ events, often crossing unfamiliar thresholds for the first time.

The partnership team hoped to provoke dialogue by addressing overlooked issues and by honoring both victims of the tragic events of 1913-1915. The interfaith Yizkor Service at Congregation Ner Tamid on August 17 focused on the remembrance of Leo Frank but also incorporated commemoration of Mary Phagan. The most well-attended event in the series, “The Leo Frank Case: 100 Years in the Media,” featured a panel with prominent local journalists, a media scholar, and a former governor. The panel summarized the media’s involvement with the Leo Frank case but also reflected on current public issues involving the media and conflict, including the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014; the Boston Marathon Bombing in 2013, and the Charleston, South Carolina, shooting in 2015.

Dr. Matthew Bernstein talks with attendees following “The Leo Frank Case: 100 Years in the Media” panel and dialogue on September 21, 2015. Photo credit: Museum of History and Holocaust Education

A shared strategic mission enabled the public history institutions to present a united front to the public and media in the face of potential controversies, and the higher number of involved professionals necessitated clear communication and frequent review of objectives. That’s not to say all challenges were anticipated; along the way, the partnership identified room for improvement. There were several overlapping events hosted by outside institutions (two memorial services were held at the same day and time, just miles apart), and at times, community members experienced confusion over who represented what initiative: a local rabbi erected a “Leo Frank Was Innocent” billboard in close proximity to the Southern Museum, and some visitors assumed the Southern Museum owned it.

The partnership among the three museums made possible the increased numbers of visitors, the infrastructure, and the strategic mission and demonstrated public history’s potential to tackle challenging issues, especially those previously repressed by the community. Southern Museum director Richard Banz’s statement to 11Alive reiterates this sentiment: “[The trial and lynching] were very grotesque, horrifying scenes of our past […] the only way that we ever really rid ourselves of that is to have open dialogue.”

~ Anna Tucker is Public Relations and Marketing Manager for the Kennesaw State University Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books. She is currently pursuing a masters degree in history at Georgia State University.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dinnerstein, Leonard, and Mazal Holocaust Collection. The Leo Frank Case. New York: Columbia University Press, 1968.

Oney, Steve. And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank. New York: Pantheon Books, 2003.

Scott, Thomas A. “Cobb County.” New Georgia Encyclopedia (accessed October 27, 2015).

[1] Leonard Dinnerstein’s The Leo Frank Case (1968) sparked public interest in the scholarly review of the Leo Frank case; however, Steve Oney’s And the Dead Shall Rise (2003) is now widely considered the more popular and authoritative text on the subject.

[2] Scott, Thomas A. “Cobb County.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. Accessed October 27, 2015. 2013 figures provided by Scott via the US Census Bureau.

[3] In 1986, the Georgia Board of Pardons and Parole granted Leo Frank a pardon based in part on the State’s lack of protection for Frank and his subsequent lynching. While many protested that this pardon stopped short of full exoneration, others, including the grandniece of Mary Phagan, firmly oppose his innocence.

Were there any real signs of public resistance to this program?

@Phillip Seitz:

Great question. There were some disorganized appeals to local media and also at the public events that exhibited resistance to the perceived content of the commemorations. The son of a lynch party member publicly spoke at a Congregation Ner Tamid event featuring guest speaker Marietta City Councilman Van Pearlberg and also at the aforementioned media panel (here’s an article summarizing his views). Also check out the comments on these Marietta Daily Journal articles here and here; they’re an interesting representation of some residents’ opinions of the commemorative events.

Most of the displays and speaking engagements at the events held by these politically correct social justice warrior (SJW) museums are decidedly pro Leo Frank and making the entire case out to be about religious bigotry. So you never get to learn about the other side of the case. The Leo Frank Research Library online gives people all the facts about the case that have been suppressed by the Jewish community for more than a century. The American Mercury online has an excellent series detailing all the facts these museums suppress.

The Leo Frank Research Library website that you refer to is clearly anti-Semitic, as even a cursory glance through its ‘About’ section (or any part of the website, for that matter) reveals. Equally important, however, is the idea that no one, regardless of guilt or innocence, deserves an extrajudicial lynching by a mob. By arguing for ‘the other side of the case’ you seem to be defending what runs contrary to American democratic ideals. The lynchings that occurred so frequently for so many years of our history (and still occasionally do) should be condemned, regardless of what you think of the lynching victim’s guilt or innocence.

Leo Frank was sentenced to hang by the neck until dead by the presiding judge leonard roan. Franks conviction was upheld by all appeals courts. Governer Slaton was law partner of leo franks trial attorney luther rosser a gross conflict of interest.

The Antigentilism in the Leo Frank case is more prevalent than the Antisemitism. This fact can not be denied now that new evidence shows Leo Frank tried to racistly frame his heinous crime on two of his black employees. Racial epithets like Antisemitism and Antisemite are being used as a scarewords to put people on the defense and raise emotions to cloud looking clearly at all the facts that have been suppressed by Leo Frank partisans for more than 100 years.

Leo Frank told the jury he might have unconsciously gone to the toilet in the metal room, to explain why Monteen Stover found his office vacant that was the exact time he formerly told police Mary Phagan was alone with him in his office.

Since every court rendered in their majority decisions that Leo Frank had a fair trial, his death sentence commutation by his attorney Luther Rosser law partner Governor John Slaton was a nullity. John Slaton should have recused himself from making a decision since he was basically commuting the death sentence of his own law firm’s client. The commutation was an injustice and totally illegal given Slaton’s oath of office. Leo Frank’s execution was not by some alcohol fueled mob whipped up in a feverish frenzy, lynching someone on a moments notice who was accused of rape or murder. Frank had two years of appeals, he was executed calmly, dispassionately and deliberately by numerous leading government officials on Sheriff William Frey’s property. The 800 year old jury system could not be beaten by corrupt people and money. The men who hanged Leo Frank were rightfully fulfilling the sentence of the jury, which not only unanimously ruled Leo Frank was guilty, but they recommended a sentence of ‘no mercy’, which implied hanging by the neck until dead. Judge Roan refused Leo Frank’s appeal for a new trial on 107 grounds, that’s not a typo! Even the Georgia Supreme Court ruled the evidence at Leo Frank’s trial was sufficient for a guilty verdict, but you wouldn’t know what that evidence was since it has been suppressed for 100 years. Leo Frank and his defenders, then and NOW, are still trying to subvert this justice, which is why this case will not be closed until his posthumous pardon is overturned, then and only then will there be justice for Mary Phagan. So until then, we the people of the world are still seeking justice for Mary Phagan. Since 1986 justice for Mary Phagan has been half-heartedly overturned with a half-baked pardon that did not officially absolve or exonerate Leo Frank. We the people demand these museums fully present both sides of the case, not just the defense, without racial epithets of antisemitism, antisemite or racism being used. The prosecution side of the case never gets a fair hearing because of Leo Frank partisanship.

The American Mercury is producing and publishing a free audio book series on the Leo Frank trial brief of evidence from 1913, including the closing arguments of prosecution and defense counselors: Luther Rosser, Reuben Arnold, Frank Hooper and Hugh Dorsey. I encourage everyone to learn what really happened by listening to this very well researched and scholarly analysis of the Leo Frank trial.