My Encounter with History at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

17 October 2019 – Lena Lannutti

archives, Philadelphia, historical societies, libraries, 2019 archives month series, history of childhood, internships

Editors’ Note: This is one in a series of posts about the intersection of archives and public history that will be published throughout October, or Archives Month in the United States. The series is edited by National Council on Public History (NCPH) board member Krista McCracken, History@Work affiliate editor Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan, and NCPH The Public Historian co-editor/Digital Media Editor Nicole Belolan.

Working with primary sources can provide a gateway to the past but also help emerging professionals get firsthand exposure to the work of archives and public history. Last summer, to enhance my internship at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP), I participated in a Public History Practicum at Temple University, where I am now a history major. The combination of practical work experience juxtaposed with learning theoretical concepts of public history provided me with insights on how my work connected to the field itself. The Practicum widened the lens of my experience through critical thinking and helped me understand the context of my work in public history.

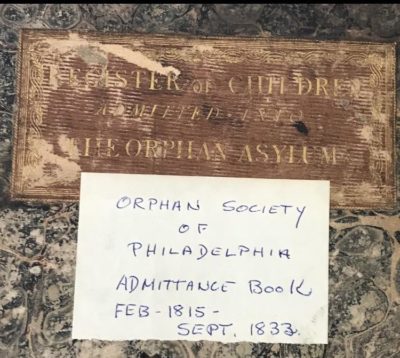

Admission Book 1815-1833, Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Photo credit: Lena Lannutti

The collection of HSP spans from early Philadelphia history to sources created in the 21stcentury. Photographs, newspapers, and graphics are a major component of the institution’s collections. My supervisor assigned me the Orphan Society of Philadelphia (1814-1965) records to work with during my time at HSP. Other interns did similar work with the Children’s Aid Society.

At HSP, I transcribed documents and researched the Orphan Society. My work engaged with letters to the Orphan Society, admission books minutes, and visiting committee reports. I first worked with the Visiting Committee Reports, volumes 13 and 14, that dated from 1823 and 1837, respectively. These weekly reports of administrators provided analysis of daily life in this institution. Descriptions about the dietary habits of the children and the cleanliness of the asylum add to our understanding of institutional childcare in of American history. Analyzing a report can build connections between a childcare today and how it differs from children in the 19thcentury.

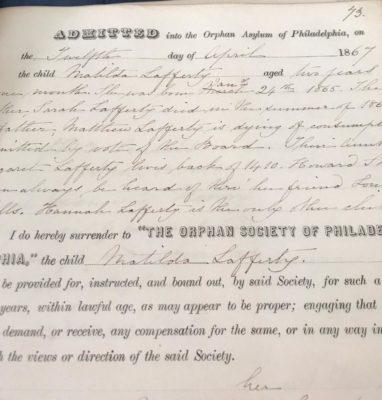

My next project focused on the Admissions Book, Volume 70, 1864-1903. Before I did any work with Volume 70, I read a previous volume to get accustomed to the format of the source (Figure 1). The Admissions Book includes rich descriptions of a child’s family history. For example, it describes an orphan, Matilda Lafferty, and includes her parents, aunt, and sister, Hannah, who also was admitted to the asylum. This Admission Book sheds light on many children that lost both their parents. In some cases, it is the only source of information about these family connections. I also read through letters written to the administrators of the Orphan Society. Spanning a half century from 1870 to 1920, these letters provided context for the Orphan Society’s longevity. Documents such as the letters provide evidence of social changes that affected Philadelphia in the period from its rapid industrial expansion through World War I.

My daily tasks involved reading the documents, then either summarizing or fully transcribing the content into an Excel spreadsheet. The spreadsheet used a standard format that could later be uploaded into a database called Encounters. By putting this information in the Encounters database, the HSP provides greater access to one of their collections and enables these documents to be more easily viewed through modern search engines. The emphasis on genealogical information when writing about this collection was intentional since family history researchers are a major audience for the HSP.

Matilda Lafferty Admission record, page 75, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Orphan Society of Philadelphia Collection. Photo credit: Lena Lannutti

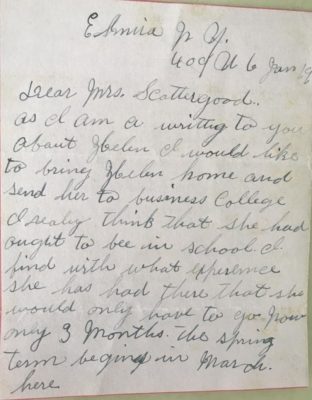

This was my first experience in an archive and these primary sources opened a window into humanity for me. I spent countless hours reading through heartbreaking letters from parents begging Orphan Society administrators to return their children. When a parent or guardian surrendered a child to the Orphan Society, they relinquished full custody by signing the admission book. Many parents expected that once they could establish some stability in their homes they could have their children back. In one letter, a mother, Rose Cooper, explained after her remarriage, “You see I am a Jewish woman and the Man I am married to now is of my own religion and I would like very much to have my little girl brought up to her own religion.”[1] This reflects the asylum’s policy of Christian-based teachings and how it affected a multicultural Philadelphia. Despite appeals such as Rose Cooper’s, the administrators often thought that their care for a child was superior, and they retained custody.

More than one hundred years later, I read these documents, and they conveyed the deep sense of desperation that these families felt. This emotion added further relevance to my work and motivated me to work harder even when the tasks seemed repetitive. The research gave me freedom to think of the collection critically, and it revealed the experiences of children in the historical narrative.

Letter from Mrs. Rose Cooper to Mrs. Scattergood January 2, 1923, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Orphan Society of Philadelphia Collection. Photo credit: Lena Lannutti

My research assignment was to take a few examples of the letters I had been transcribing and connect them with a theme. The most interesting aspect that I had found in these documents was family connections, which was unexpected given the circumstances of custody issues. After writing a draft of the piece, my supervisor suggested I use other documents to develop my argument from many perspectives. This suggestion allowed me to more fully immerse myself in the collection and the policies of the Orphan Society. It gave me a chance to read through one of the Minutes volumes, which provided an earlier instance of parental custody issues than my work had established.

I had an amazing time over this summer. The experience broadened my understanding of public history and allowed me opportunities that I could have never imagined. I developed new skills such as understanding 19th-century handwriting and learned more about an integral part of my local community. The routine of my work could be repetitious, but my engagement in the material fueled me throughout the days and months. I find it especially rewarding that my work will one day aid fellow researchers and that through my input into the Encounters database a legacy of my summer now exists. I learned this summer that a time machine does not have to take the form of Back to the Future‘s DeLorean or Dr. Who‘s blue police box. Archives such as the Historical Society of Pennsylvania open a portal to the past.

[1]Mrs. Rose Cooper. Mrs. Rose Cooper to Mrs. Scattergood January 2, 1923, Letter Historical Society of Pennsylvania Orphan Society of Philadelphia Collection.

~Lena Lannutti is a junior history major at Temple University, graduating in Spring 2021.