Archiving the GTMO experience: an ongoing public collaboration

24 January 2014 – Holly Ackerman

Editor’s Note: This piece continues a series of posts related to the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, a collaboration of public history programs across the country to raise awareness of the long history of the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) and foster dialogue on its future. For an introduction to the series, please see this piece by the Project’s director, Liz Ševčenko.

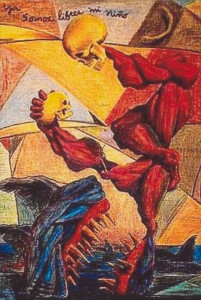

“Now we are free, my child” crayon on paper by Sergio Lastres, created while held in Guantánamo camps, 1994. Photo credit: Siro del Castillo from Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

In 1992 I moved to Miami to enroll in a PhD program at the University of Miami’s Graduate School of International Studies. In general I wanted to focus my studies on Cuban migration and the Cuban exile community in Miami. The specific topic that would occupy me for the next five years was stimulated by small articles that appeared in the local newspapers announcing the rescue of groups of Cuban balseros–people who had set out in homemade rafts trying to reach the United States. The rafters seemed to provide a case example that could address an intriguing question–why do people who have been politically and socially quiescent suddenly take bold, dangerous political and social actions? At the time, it was illegal to leave Cuba without government permission, and many people served 1-5 years in prison when caught making rafts or setting out to sea. Those who succeeded in their clandestine exit were labeled as escoria (scum), and their homes and possessions were confiscated by the state. The sea crossing was also extremely dangerous, and many rafters died or witnessed the death of others in their party.

If rescued by the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in 1992, the Cuban rafters were not taken to the US Naval Station at Guantánamo (GTMO). Instead, they were brought to the USCG station near Key West and were released to the Hogar de tránsito para balseros cubanos–a shelter located across the street from the USCG. The Hogar was organized and run by Cuban-Americans living in Key West to house and feed the new arrivals for short periods while arranging their transport to Miami. In Miami they were “processed” by church-sponsored refugee resettlement agencies under contract with the US government and then released. The short newspaper stories about these seafarers were so compelling that I called the Hogar in Key West and received permission to go there on weekends to interview the fast-growing numbers of rafters. The history of the Cuban rafters became my dissertation project and a life-long research interest.

Cuban rafter art, Artist unknown, created while held in Guantánamo camps, 1995. Photo credit: Siro del Castillo from Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

By 1993, I gained permission from the refugee resettlement agencies in Miami to come to their offices and interview rafters who were awaiting processing. Within a year, the agencies had expanded from an ordinary eight-hour per day, five-day work week to a round-the-clock, seven-day schedule. The rafters were now pouring in at a crisis-producing pace. In 1994, when President Fidel Castro withdrew the Cuban coast guard and invited the exit of anyone who wanted to leave, President Bill Clinton sent the resulting surge of 36,000 rafters to GTMO and to camps in Panamá. Eventually, the GTMO and Panamá detainees were admitted to the US, and they too passed through the resettlement agencies in Miami where I met them and heard about their traumas in Cuba, at sea, and at GTMO.

In the course of my study, I was shown photos, letters, and other artifacts related to the rafting experience, and I began to dream of making these materials available for a wider public. In 2004, the Digital Services Director at the University of Miami Libraries agreed to create one of the first online digital archives. It contains photos, artwork, videos, oral histories, and legal documents gathered from rafters, local television stations, and government agencies. The resulting project, called The Cuban Rafter Phenomenon, is still freely available online, receiving tens of thousands of hits and regularly serving as an archive for secondary school classes as well as university research. I invite anyone interested in this history to visit the site. I’ve also maintained a bibliography on this subject.

Haitians at sea in 1981. Photo credit: US Coast Guard, Historian’s Office, Washington, DC from Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

When I left Miami in 2006 to join the library staff at Duke University, I submitted a successful proposal to support continued “harvesting” of archives related not only to Cuban rafters but also to the Dominicans and Haitians who set out in small boats. The Haitians also experienced detention at GTMO, first in 1991 and again in 1994. This became the Digital Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, which is also freely available.

Facsimile of 2nd edition of éxodo, November 27, 1994, a newspaper produced by Cuban rafters held in Guantánamo camps. Photo credit: Gift of Mariela Ferrer Jewett from Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Que pasa?, a newspaper prepared by the US Army MIST for Cubans held in Guantánamo camps in 1994-1996. Photo credit: Gift of Elizabeth Campisi, from Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

The most unique and valuable materials in this collection are the newspapers produced in the camps at GTMO. Some of the Cuban newspapers were produced by the detainees themselves, including éxodo, El futuro, and El Bravo. Others were published by the military’s psychological operations staff (known as a MIST or Military Information Support Team) who were tasked with rumor control and information sharing in both the Haitian and Cuban camps. The Haitian MIST newspaper was called Sa K’Pase and the Cuban MIST produced Que Pasa? . Taken together these newspapers offer a partial picture of life in the camps viewed from different perspectives. The MIST publications are also instructive for contrasting the government approach toward the Haitians who were sent back to their homeland versus the Cubans who were to enter the United States.

Sa K’Pase, a newspaper prepared by the US Army MIST for Haitians held in Guantánamo camps in 1992. Photo credit: Gift of Steven Brown, from Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

My plan is to continue expanding the analog collection and to have new materials digitized periodically. Any reader who has related items that might be included is encouraged to contact me at [email protected]. Hopefully the preservation of these materials and their universal availability will help us to understand the historical causes and consequences of our presence at Guantánamo.

~Holly Ackerman is the Librarian for Latin American, Iberian, and Latino Studies at the Duke University Libraries where she has curated exhibits on Caribbean Sea migration; the Puerto Rican diaspora and the Deena Stryker Photography Collection on Cuba. Dr. Ackerman is a graduate of Howard University and earned a master’s degree from Columbia University and a PhD in International Studies from the University of Miami. She is the author of The Cuban Balseros: Voyage of Uncertainty which established the demography and social history of Cubans who emigrate by sea. She publishes regularly on the social history and geopolitics of Cuban, Dominican, and Haitian migration.