Audience analysis and the role of the digital in community engagement

22 March 2016 – Kerri Young

audience assessment, "Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology" responses, public engagement, community history, digital history, The Public Historian, TPH 38.1, digital divide

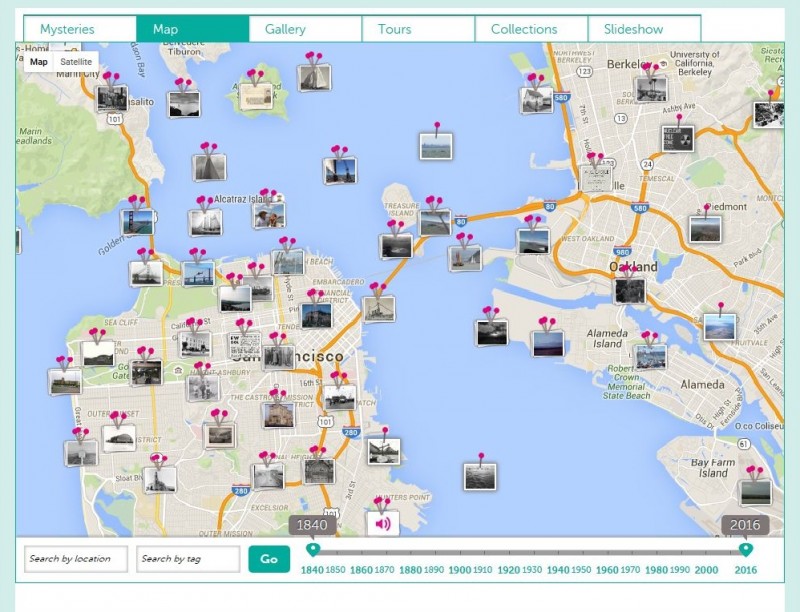

Map from the Bernal Heights Year of the Bay project on Historypin. Photo credit: Historypin

As a public historian working on the collaborative digital platform Historypin, I second Andrew Hurley’s assertion, in his article “Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology: Public History Meets the Digital Divide,” that introducing more traditional methods of engagement can, and most often is required to, enhance the efficacy of the digital tools within a public history project. At Historypin, this blending of the more traditional (community meetings, analog forms, etc.) with the new (platform-based interactions, social media) continues to prove an effective approach to digital engagement projects with diverse audiences. Additionally, we have increasingly found that carrying out an initial audience analysis is key to leveraging these two aspects of engagement. Hurley does not mention whether the Virtual City Project began with any kind of audience analysis, but this step has proved crucial to our projects in terms of setting realistic goals and boundaries for digital implementation.

My experience working with the Bernal Heights History group on the Year of the Bay project, a partnership between Historypin and Stanford’s Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis in the Humanities, illustrates how only a vague understanding of one’s audiences can prevent one from developing an engagement strategy that strikes the right balance between the use of digital tools and more traditional methods. Our aim was for project participants to help diversify and enrich our understanding of the environmental history of the San Francisco Bay through the contribution of crowdsourced materials.[1] One of my roles as project officer was to facilitate and measure community engagement among loosely targeted museums, archives, and community groups, such as Bernal Heights History, and promote Historypin as a platform where these communities could share expert knowledge with a broader audience.

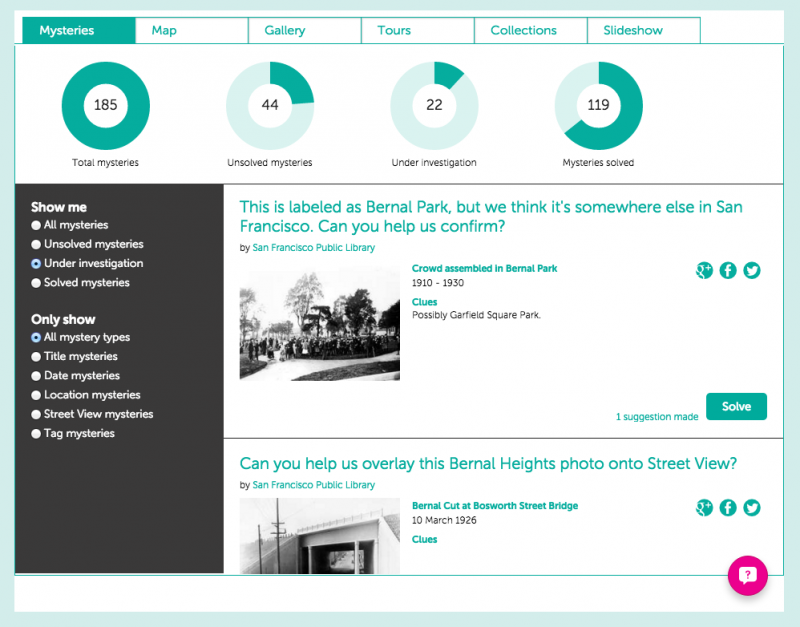

Bernal Heights metadata crowdsourcing mysteries, Year of the Bay project. Photo credit: Historypin

The Bernal Heights History group is a small gathering of mostly older local history enthusiasts who meet once a month to discuss the history of San Francisco’s so-named quiet and suburban-like neighborhood on the southern edge of the city. Our digitally led engagement approach with this group, and many similar groups we encountered over the course of our outreach, revealed that digital literacy barriers, as well as a lack of resources and time, will limit participation in such projects. Yet this group also demonstrated that a simpler use of digital tools can enable rich storytelling and knowledge sharing.

For example, when we presented a new set of Bernal Heights mysteries (contributed to Historypin via the San Francisco Public Library) to the group, each member excitedly discussed these never-before-seen images of their neighborhood and posited what or where certain photos might have been taken. A humble projector allowed us to zoom in on photographic details and scroll between the metadata mysteries on offer to start topics of conversation. Though we did not actually record much in these sessions, they were very rewarding, in that they generated meaningful discussion over local history. (I, as project facilitator, was able to record some of these observations after the fact.) The digital tools ended up serving as a catalyst for this discussion, enhancing what this community loved to do on a regular basis. The experience underlined the importance of identifying and understanding the audience in order to inform the digital tools.

We have continued to build upon this strategy at Historypin, more recently in a pilot project with a San Francisco assisted living facility, Rhoda Goldman Plaza. Like the session in Bernal Heights years earlier, this experience highlighted the potential for what Hurley calls “guided encounters” with digital tools to have meaningful impact with specific audience groups.

This pilot was part of Sourdough & Rye, a project focused on the Bay Area Jewish community. The pilot gave us the opportunity to do a deep dive into how digital tools can successfully complement more traditional engagement methods when applied to a specific audience. Iterative by design, our project aimed to use Historypin to create new forms of interaction among potentially isolated seniors. Though one of our main outputs was digital, it was purposefully secondary to the social goals of the exercise.

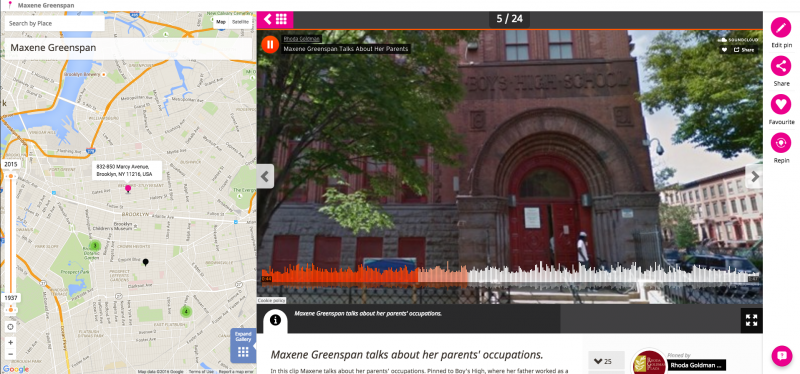

Combining recorded audio with place, part of the Rhoda Goldman pilot. Photo credit: Historypin

We used a multi-session format, in which we worked with a handful of seniors to help them tell the stories of their lives through the lens of important places. At the same time, we thought about the kinds of materials we would need to digitally record and present these memories. Given the low rate of digital literacy among people in the age group we were working with (70 to 100), we ultimately decided upon a virtually “no-tech” set-up, with initial iterations comprised of filling out story-collection sheets in groups, creating a booklet that corresponded to the Tour functionality on Historypin, and using simple audio recorders.

Project coordinators and volunteers took on the digital legwork of putting together the Tours, with a goal of mapping the interviews. A digital Historypin Tour that we had put together for resident Maxine Greenspan, for example, allowed us to view locations of places she had lived as they look today, on Google street view. This enabled new reflections and stories and demonstrated the power of digital tools to enhance an already rich life narrative. Like the Virtual City project, we were able to explore digitally places not revisited in a long time and, through guided interactions, help members of a particular group reflect upon their lives in a social setting.

My experience with Year of the Bay and the Rhoda Goldman Plaza pilot has taught me that public historians working with digital platforms cannot underestimate the power of getting to know our audiences. In addition to informing the balance and combination of personal and digital interaction, audience analysis is a critical first step in designing digital tools that will have the greatest social impact.

[1] Jon Voss, Gabriel Wolfenstein, and Kerri Young, “From Crowdsourcing to Knowledge Communities: Creating Meaningful Scholarship through Digital Collaboration,” MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015, published February 1, 2015, http://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/from-crowdsourcing-to-knowledge-communities-creating-meaningful-scholarship-through-digital-collaboration/.

~ Kerri Young is a Historypin community officer in San Francisco, helping implement and experiment with new audience participation strategies to promote engaging programs within the cultural heritage sector. She is currently working with the US National Archives on a World War I and World War II moving-image engagement project.

Editor’s note: In “Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology,” published in The Public Historian (38.1), Andrew Hurley discusses the implications of the digital divide when working with diverse audiences and striving for public engagement. This is the second of five posts (the first post is here) that will be published by The Public Historian responding to Hurley’s article.