Can Facebook help public historians build community?

11 August 2017 – Paul Ringel

William Penn High School homecoming queen Ruby Jenkins riding in a convertible automobile driven by Leon Sharpe, Jr. Seated in the back seat on either side of Jenkins are Bernice Wall (left) and Doris Wall (right). Courtesy of the High Point Historical Society, High Point Enterprise Negative Collection.

Consider a public history project on a Jim Crow era black high school in North Carolina, staffed by a white professor and three dozen predominantly white students. Add a growing level of distrust between the private, rapidly expanding university from which the project emerged, and the poor, largely non-white, surrounding community that was the home neighborhood for this high school. What tools might be helpful for bridging these divides? Facebook may not appear near the top of your list, but on this particular project the social media application has proven a surprisingly effective instrument for bringing students, faculty, and community together across informational and cultural chasms.

I teach a class at High Point University for upper-level undergraduates—who are primarily history majors—called The History Detectives. The course is designed to take the skills these students have learned in their previous courses and put them to work on a joint local history project. Our most recent project focused on William Penn High School, opened by Quakers in the 1890s for African Americans who had no other access to secondary education, and which remained the only high school available to most local blacks in and around High Point, North Carolina until desegregation in 1968. Students working on the William Penn Project performed archival research, conducted oral history interviews with William Penn alumni (after receiving training from the Southern Oral History Program of the University of North Carolina), and constructed a nearly-completed website on the history of the school.

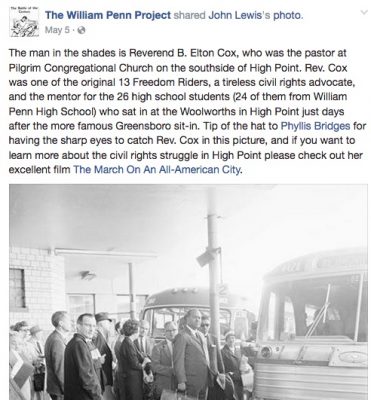

I initially set up a private Facebook page for the class so the students could share information—and their excitement—about archival discoveries, as well as networking connections with alumni, librarians, museum professionals, and community historians. When our progress slowed after an initial wave of successes, the group created a separate, public Facebook page through which we could cast a wider information-gathering net. The idea was to publicize our project to a larger audience in the hopes of procuring more interviewees and more information on some of the archival materials that were stymieing us. Who were the people in that picture? What else can we learn about this teacher? When did that game or protest or performance take place? These were the types of questions that we hoped our Facebook followers might answer.

I initially set up a private Facebook page for the class so the students could share information—and their excitement—about archival discoveries, as well as networking connections with alumni, librarians, museum professionals, and community historians. When our progress slowed after an initial wave of successes, the group created a separate, public Facebook page through which we could cast a wider information-gathering net. The idea was to publicize our project to a larger audience in the hopes of procuring more interviewees and more information on some of the archival materials that were stymieing us. Who were the people in that picture? What else can we learn about this teacher? When did that game or protest or performance take place? These were the types of questions that we hoped our Facebook followers might answer.

At first the people who liked the page were mostly families and friends, but over the course of several months William Penn alumni and their children and grandchildren began to pay attention to the stories and artifacts that we posted (with appropriate permissions). Our concerns that the alumni, the youngest of whom are in their late sixties, would not be on Facebook proved unfounded. Indeed, their patterns of engagement showed that they not only found our page but were sharing it with each other.

Those patterns also made clear that alumni and families were much more willing to respond to some inquiries than others. Requests on the page for more interviewees drew almost no feedback; soliciting that level of engagement required a more personal–and often a repeated—connection with alumni by phone or in person. In contrast, the page proved an excellent resource for gathering information about archival materials. Posted photographs instigated alumni to provide details about varsity basketball teams, honor society ceremonies, and lunchtime social practices. A post about football coach James Atkinson produced over 1700 engagements, including poignant stories about his post-William Penn career at an integrated school that we did not know but later were able to corroborate independently. My favorite post was a response to a photograph of an unknown young man bowling; we asked for information, and a woman answered, “That is my daddy!”

Those patterns also made clear that alumni and families were much more willing to respond to some inquiries than others. Requests on the page for more interviewees drew almost no feedback; soliciting that level of engagement required a more personal–and often a repeated—connection with alumni by phone or in person. In contrast, the page proved an excellent resource for gathering information about archival materials. Posted photographs instigated alumni to provide details about varsity basketball teams, honor society ceremonies, and lunchtime social practices. A post about football coach James Atkinson produced over 1700 engagements, including poignant stories about his post-William Penn career at an integrated school that we did not know but later were able to corroborate independently. My favorite post was a response to a photograph of an unknown young man bowling; we asked for information, and a woman answered, “That is my daddy!”

The Facebook page has helped our students to bridge an information divide and procure details about William Penn’s history from alumni whom the students otherwise were struggling to reach. It also may be facilitating face-to-face engagement between the two groups. We know a growing number of alumni are visiting and digging through our Facebook page, even as we have scaled back our efforts in order to finish the website. In recent months, they have liked and left brief supportive messages (“this project is interesting to me,” “good work,” “thank you”) on posts that are one or two years old. At the same time, alumni resistance to our Project has diminished. In 2017, we have found more alums who are willing to sit for interviews than at any time since our initial wave of contacts in 2014. Much of this change is the product of persistence; we keep talking to people and showing up at community events related to William Penn and African-American history in High Point, which in turn helps to strengthen our network among the alumni and their families. Still, it is worth considering whether our Facebook page may be creating opportunities to develop the substantial new community relationships that we seek to nurture within our city.

Assessing whether Facebook is strengthening our new community partnerships is challenging. Recent interviewees have indicated that it was fellow alumni or other community members rather than the Facebook page that brought the Project to their attention, but that does not preclude the possibility that the page is heightening awareness or enthusiasm within the broader community. Public historians offer insights into the challenges of attracting attention and engagement on digital platforms, and journalists highlight success stories in which social media campaigns led to improved face-to-face engagements within already established communities, but neither directly address the questions we have developed. If readers have had experiences using Facebook or other forms of social media in this or similar ways, we would love to hear from you! In the meantime, as we consider the most effective ways to gather data on this issue, there seems to be little downside to continuing with our blended approach of using Facebook and more traditional methods to forge stronger community ties.

~ Paul Ringel is an associate professor of history at High Point University. He is the author of Commercializing Childhood: Children’s Magazines, Urban Gentility, and the Ideal of the Child Consumer in the United States, 1823-1918 (2015). The William Penn Project is his first endeavor directing a public history project.

Paul, I enjoyed reading your post and learning more about High Point University, its history and your project. I tend to share information via Facebook with those interested in the project I manage at my university, but it is done through my own personal FB account rather than through a FB account specific to our project. At first I was hesitant to blur the boundaries between my personal and professional life, but it has helped be build relationships and develop more trust. it is ESPECIALLY helpful for connecting with people all around the nation. I think that for projects that have a lot of visual content it can be a great way to readily share photos and video, and allow others to “share” or “re-post” material. I think the trick is to keep sharing new information on the FB page — regularly, to keep people coming back and sharing material. It would also be neat if you had your students do videos…even just on their cell phones, and share them on the site. Perhaps they could talk about what working on the project has meant to them personally and intellectually.