Confederates out of the attic

02 July 2019 – Tyler Rudd Putman

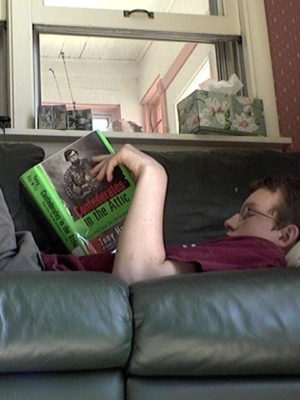

The author reading Confederates in the Attic, about 2002. Photo credit: Tyler Rudd Putman

Like many of my friends and colleagues, I’ve been reflecting on the work of journalist Tony Horwitz, who died suddenly on May 27th. Horwitz’s 1998 book, Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War, had a profound impact on American popular culture, public history, and on my own personal and professional life. More than any book before or since, it exposed how our country’s ongoing fascination with the Civil War was as troubling as it was entertaining, and it brought reenacting and reenactors to the forefront of that conversation. Twenty-one years later, we still live in the shadow of the Civil War. Horwitz grappled with the dark side of Confederate memory, and no author since has achieved what he did: showing how Americans experience this memory and public history in many forms, from nightmarish to comic. Indeed, it may no longer be possible—or socially acceptable—for these forms to coexist in America.

I first encountered Confederates in the Attic in 2002, when I was fourteen, during the summer when I decided to become a reenactor. That’s me in the photo above reading a library copy around the same time. I’d long nurtured a fascination with the Civil War, but I lived in northern Michigan, far from any battlefield. It was still somewhat difficult to learn much about reenacting—or how to become a reenactor—from the nascent internet. But right around the time I found Horwitz’s book, a new organization of reenactors formed in my small town. That book and that unit swept me into the world of reenacting, taking me places that would have been hard to imagine when I was growing up.

The most memorable parts of Horwitz’s book—and the ones that garnered the most attention at the time of its publication—focused on the culture of reenacting. In the mid-1990s, as we can see in hindsight, Civil War reenacting reached its apex. Popular documentaries, movies, and books had inspired a new surge of interest in the war. Reenacting had begun in its modern form in the early 1960s. The 135th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1998 was the largest reenactment in history. Thousands of men and women were discovering and pursuing this hobby when Horwitz wrote about it.

In some ways, Horwitz’s book is now a primary source in its own right, depicting a specific moment in American public history. The Southern Guard—the “hardcore” reenacting unit that Horwitz serendipitously encountered in his front yard—is long gone, but many of the young members that he met went on to do remarkable things. Chris Daley (then a paralegal) is now in charge of costuming the staff of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation; Joel Bohy (then a construction worker) directs the arms and militaria department at Skinner Auctioneers; Paul Carter (then finishing a dissertation on Russian history) is the American Consul General in Russia. Robert Lee Hodge, a central character in the book and the subject of its cover photograph, used his sudden fame to advocate for battlefield preservation and make historical films.

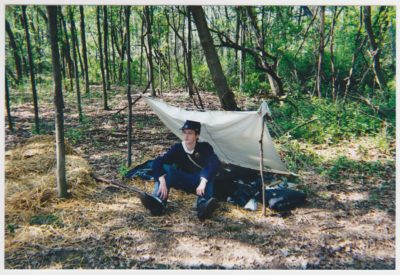

The author as a Union soldier, 2003. Photo credit: Tyler Rudd Putman

In the generation of reenactors just behind these men, I came of age in reenacting. I “fought” on Civil War battlefields that a few years before had been only vague names on book pages, as you can see in the photo of me at right. Reenacting led me to seasonal work in costumed living history interpretation. It connected me to an internship which helped me secure a spot in a funded graduate program. All of that and the network of people I came to know through reenacting contributed to the job I have now, as the Gallery Interpretation Manager at the Museum of the American Revolution. In that role, I plan and create costumed living history programs in which interpreters show the complexity and diversity of the American Revolution. I still dress up like old soldiers. Horwitz’s reenactors were mostly white men, and while reenacting is still a predominantly white hobby, I get to work with some remarkable women and people of color who portray early America in all of its diversity.

During the sesquicentennial of the Civil War (2011-2015), as I participated in anniversary reenactments, I frequently heard people express dismay over the level of public interest in the events. People just didn’t care about history anymore, they’d say. And yet just after the anniversary events ended, Americans rediscovered the unfinished Civil War—the Confederates in their attics—in the most tragic ways in the church shooting in Charleston and the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville. Suddenly, people who could not have cared less about the anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg found within themselves strong historical opinions about Confederate flags and statues. This was precisely the sort of collective memory and public history that Horwitz wrote about.

It would be a mistake to say we live in more complicated times today. Plenty of people in the 1990s recognized (and experienced) the insidious, violent nature of some forms of Confederate memory. Horwitz met people engaged in divisive debates about Confederate flags flying over state capitols that sound eerily familiar to our own fights over Confederate statues. It hasn’t gotten any easier to talk about the Confederacy in the years since Horwitz’s book appeared. Confederate iconography was central to Dylann Roof’s act of racist mass violence in Charleston and the Charlottesville rally; it also featured in the reporting on these events. It would take literary genius today to treat other forms of Confederate memory—reenacting, battlefield tourism, popular literature, the souvenir market, and so on—with the sort of sympathetic humor that Horwitz brought to them in the 1990s. Shortly before he died, Horwitz published a new book, Spying on the South. Those of us who were changed by Confederates in the Attic have been given this last chance to have Horwitz as our guide in reckoning with the modern South.

By bringing Civil War memory and reenacting to the forefront of American consciousness, Horwitz’s book did a great service to public history. It presented reenactors as remarkably peculiar people—which many of them are—but it did so with a rare depth of sympathy. Like the best journalists, Horwitz blurred the lines between participant and observer. He wrote so well about people who loved the Civil War because he loved it himself. His book challenged us to see the best and worst legacies of the Civil War everywhere we look. They’re still there.

~ Tyler Rudd Putman is the Gallery Interpretation Manager at the Museum of the American Revolution and a Ph.D. Candidate in the History of American Civilization Program in the Department of History at the University of Delaware.

What a well written article. I am of the same age group, read the book at the same time, and experienced some of the best reenactments at [what to a fourteen or fifteen year old remembers as] the zenith of reenacting. I was unaware and am saddened to hear that Tony Horwitz had passed. He made the world we were just discovering first person so much more exciting.

Speaking for those of simpler times (I was born to Greatest Gen parents in the final year of the Boom), I can tell you Tony was a rare breed, in that despite ingrained sensibilities, *he listened*. Or, I thought he did. Confederates in the Attic, is one of my favorite books of all time. Spying on the South, wound up in the garbage. I think TH had had it, in trying to bridge any gap, re: what I refer to in my own work as “Twain America”…and as someone reared on MARX playsets and History, I found “Spying…” one-sided in the extreme. Which, doesn’t dampen my enthusiasm for the earlier work, though the world of reenacting, like any group based activity, isn’t something I pretend to understand. Unlike many other “groups”, it’s chocked with its own brand of diversity. And unlike many encountered by TH outside this insular world of grunge and dietary stringency, the reenacting world found its fun, its own America.

I hadn’t thought this nation would deteriorate so badly, so that only technology in everyone’s hand, prevents insurrection. Next to the events of Today, as I near my dotage, the 90’s seems like a damned playground! Also a place to meet, and to talk.