Disrupting authority: The radical roots and branches of oral history

03 March 2017 – Linda Shopes and Amy Starecheski

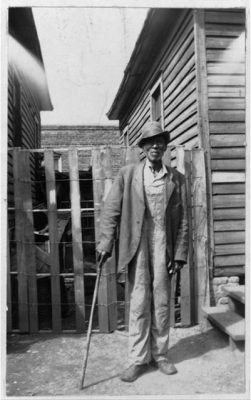

William Colbert of Alabama, ca. 1936. Born in slavery, Colbert was interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project. Photo credit: Library of Congress

Oral history, like public history, is now old enough to have its own history, its own founding narrative. As one might expect from a field so deeply devoted to challenging incomplete and exclusive narratives, oral historians are now asking what is left out of their own history and filling in some of the gaps they have found.

Historiography typically locates oral history’s origin in the United States with the work of journalist-turned-historian Allan Nevins at Columbia University, who in 1948 established what is generally recognized as the country’s first and largest academic oral history program. The Columbia program was soon followed by similar programs at other universities, libraries, and historical organizations, given impetus, in part, by the widespread availability of relatively lightweight, inexpensive tape recorders. For Nevins and many others, oral history has been understood as a fundamentally archival practice: to record and preserve new knowledge about the past for future use. The task of the oral historian, from this point of view, has been to add interviews to the extant record, providing new evidence for future users, understood primarily as scholars and other serious researchers, to create more complete histories.

But this is only part of the story. Oral history, i.e. in-depth interviews with individuals knowledgeable about aspects of the past, existed well before the work of Nevins at Columbia—one has only to think of the Federal Writers Project interviews, for example. Moreover, scholars, activists, and artists have long been developing projects and conducting oral history interviews, not solely for archival purposes but for a variety of social purposes, with public outcomes in the present—dramatic presentations, exhibits, forums, walking tours, films, websites, and so on. As Daniel Kerr has recently shown in his Oral History Review article titled, appropriately, “Allen Nevins is Not My Grandfather,” at times oral history has been used to anchor—to inspire and support—progressive social action; indeed, it has been deeply implicated in movements for social justice.

A gathering of Groundswell: Oral History for Social Change at the 2015 Allied Media Conference in Detroit. Photo credit: Groundswell.

We can trace our roots back not only to the archive, but also to the spaces of organizers, from the Highlander Folk School in Appalachia in the 1930s through the 1950s, to the Massachusetts History Workshop in the 1970s and 1980s. Today many activist oral historians, as well as cultural workers, community organizers, and documentary artists, have coalesced around Groundswell: Oral History for Social Change, a network of practitioners who use oral history in creative ways to support movement building and transformative social change. Yet the historiography of oral history has typically obscured or marginalized these more expansive roots and branches of the field.

As part of the Radical Roots of Public History collective research project, our group has been excavating some of the radical roots of oral history. As we seek to conceptualize the relationships between archival, public, and radical oral history, one concept we have found to be of continuing relevance is “shared authority,” first articulated by Michael Frisch in his 1990 collection, A Shared Authority, aptly subtitled Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History. According to Frisch, because an interview is intrinsically dialogic, that is, constituted by a back-and-forth exchange between two individuals with different frames of reference—different domains of knowledge or expertise—authority by definition is “shared.” An interviewer’s authority is evident in the question she asks; a narrator’s in the answer he gives. And so on. Over the years, oral and public historians have shifted the “-ed” to “-ing” and coined the term “sharing authority” to describe a collaborative relationship between communities and historians through the entire public history process, from initial conception of a project to final products. Indeed, it has become something of an ethical imperative in public history; certainly it reflects the democratic, non-hierarchical approach necessary if activist-oriented work is to achieve even a measure of success.

Still, as we consider the salience of shared authority for our work, it is perhaps useful to consider the context within which Frisch articulated it. From the 1970s onward, as interviews with those sometimes termed “nonelites” came to dominate oral history, oral historians became acutely aware of—and highly critical of—the power dynamics operating within an interview. Simultaneously, while some continued to maintain that the role of oral history was to add sources to the archive, not destabilize the traditional practice of history, others, recognizing the power of the first person voice, argued that interviews provided an unmediated and inherently valid view of the past, one not requiring the skills or critical input of the historian. “Shared authority” became a way to think though these dilemmas.

It’s important to emphasize that Frisch argued that oral and public historians must share authority with their narrators, not give it up to them. The historian must recognize and problematize her own authority, but still own it. And so today we ask, what does this look like when oral history work is done independently of the archive and the historical profession? Or when the main goal of a project is social justice, not historical knowledge? What is the value of the researcher’s skillset for social justice work? In these difficult, even dangerous times, as we seek to intervene in public life in meaningful ways, are there occasions in which sharing authority might not be advisable, when we need to exercise the authority of our knowledge? And are there times when we might better disrupt authority? In our mini-symposium at the NCPH annual meeting, we will be presenting work that actively seeks to disrupt the structures of authority that shape the production of historical knowledge and the continual reproduction of structural inequality.

~ Linda Shopes is a freelance editor and consultant in oral and public history. She is coeditor, with Paula Hamilton, of Oral History and Public Memories (2008), published by Temple University Press, and author of numerous articles in oral and public history.

~ Amy Starecheski is a cultural anthropologist and oral historian who co-directs the Oral History MA Program at Columbia University. In 2015 she won the Oral History Association’s article award for “Squatting History: The Power of Oral History as a History-Making Practice,” and in 2016 she was awarded the SAPIENS-Allegra “Will the Next Margaret Mead Please Stand Up?” prize for public anthropological writing. Her book, Ours to Lose: When Squatters Became Homeowners in New York City, was published in 2016 by the University of Chicago Press.

*This post is part of a series from the “Radical Roots: Civic Engagement, Public History, and a Tradition of Social Justice Activism” collaborative research project. You can find other posts in the series here. Research project members will be presenting a mini-symposium at NCPH’s annual meeting in Indianapolis on Friday, April 21 from 1:00-5:00 pm.