Does the “Ken Burns Effect” work in an age of social media?

01 February 2013 – Vanessa Macias

Early last year, the NBC television show Community produced an episode entitled “Pillows v. Blankets.“ The episode depicts a pillow fight that reaches epic brother-against-brother proportions by involving the entire Glendale Community College campus. It very cleverly relates the war’s progression through text messages (complete with emoticons), emails, and Facebook updates. Footage of pillow skirmishes comes from cell phones. Episodes of Community often parody elements of popular culture (a particular favorite is an episode that mocks the show Law & Order). For this particular conflict, the writers looked to Ken Burns’ popular documentary, The Civil War. The conversation below spooled out from our (Priya Chhaya and Vanessa Macias’) mutual love of pop culture and history.

Vanessa: I was so happy to hear that you found Community’s “Pillows v. Blankets” episode as funny as I did! I thought it was just the history nerd in me that was tickled by the spot-on parody of Ken Burns’ documentary, The Civil War.

Priya: I know. Part of the reason I found the episode so enjoyable was just how seriously it took the conflict, thus underscoring the Civil War’s over-dramatization in that much-beloved documentary. However, in being so obvious the Community episode illustrated the way in which our lives have changed from the 1860s. I’ll readily admit that watching the film is one of my favorite memories of my high school history class. At the time it was only a few years old (the documentary came out in 1990) and emphasized what I would later learn was social history—telling history through the eyes of ordinary people on the ground, rather than just military formations and movements. Who didn’t love hearing about the first-hand accounts and letters–or looking at the great photographs—which made the documentary so groundbreaking.

Vanessa: I remember being captivated by The Civil War when I first watched it years ago. Now the format is ripe for parody. “Pillows v. Blankets” is an effective imitation of all the signatures of the “Ken Burns Effect”—the somber voiceover, sepia-toned battle maps, fiddle-heavy soundtrack, and slow tracking shots of photographs. I stopped airing segments of the documentary in my US History classes for fear that my students’ eyes would glaze over and become heavy each time the mournful “Ashokan Farewell” plays. How can I expect my students, whose daily lives’ include instant communication via social media and text messaging, to become engaged in a documentary format that even I find slow and outdated?

Priya: Did you know that the “Ken Burns Effect” is an option on Movie Maker, the film editing software on Apple products? It is ironic that it is now an institutionalized tool to tell a story, while this episode clearly shows that it may not be effective anymore. The fact that a methodology is now a film technique makes using it all the more disingenuous. Don’t get me wrong—I do love Ken Burns’ films. He does a great job of bringing history to a specific audience. But I’m not sure if his style of filmmaking can successfully document our modern modes of communicating (through email and text messaging).

Vanessa: Hmm, I’ll have to apply that effect to the next video I record of my dog (talk about a disingenuous technique!) I, too, have a certain amount of respect for what Ken Burns has contributed to popularizing historical documentaries. Yet by using such a serious format to depict such a ridiculous conflict, “Pillows v. Blankets” shows the shortcomings of documentaries that are so intent on the gravity of history that the immediacy and uncertainty of a historical moment is lost.

Priya: I agree. Not so much white-washing but rose-colored-glassifying (if I can feel free to make up words now).

Vanessa: Maybe the answer lies in experimenting with the entire format. For example, I show my classes an episode about Shays’ Rebellion from The History Channel’s 2006 series 10 Days That Unexpectedly Changed America. This episode uses animation to depict the events leading up to the rebellion as well as talking-head interviews with historians to provide historical context. I find the episode refreshing in the same way that I like looking at colorized versions of black and white photos. Both make me take a second look and see something new. By employing new techniques to depict the past in an engaging and innovative way, we can make viewers consider the past in a different light.

Priya: Agreed. I do think though that one of the strengths of Burns’ style of filmmaking is his ability to pull out individual stories amidst a broader conflict. Which begs the question: in this era of twitter, blogging, email, and texting, how do we capture that narrative—without making it a farce?

Vanessa: Applying unexpected formats and editing techniques to documentaries (like animation) opens opportunities to slip in tweets, Instagram photos, and texts that relate the individual experience of a historical moment. The texts shared in “Pillows v. Blankets” are pretty silly, but meaningful comments are made amid the social media noise.

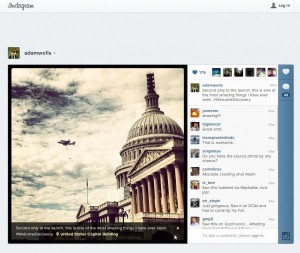

Photo by Adam Wells of the space shuttle flying past the U.S. Capitol, posted on Instagram

Priya: Take the recent retirement of NASA’s Space Shuttles. In every city that a Shuttle was sent (Cape Canaveral, Washington, DC, Los Angeles, New York City, Houston) there was a social media explosion—one that I was a part of. Sitting on an airplane at Washington Reagan National Airport I was able to tweet as we saw the Shuttle swing by the city, using the hashtag #spottheshuttle. Most of these tweets were simple declarations of sight—but a few were statements of an end of an era.

Years from now when historians try and document the moment when one door of the American space story closed and another opened, we want these reactions to be right next to the letters by John Glenn and Neil Armstrong. Why? Because they are indicative of the public’s connection to that piece of American history.

Vanessa: Exactly. Those tweets are immediate reactions that people feel an urge to share with one another. The most eloquent tweets (as eloquent as one can be in 140 characters) recall those poignant powerful moments in a Burns documentary.

Priya: This episode of Community also raises broader questions about how to interpret new styles of digital primary documentation. Is one tweet the same as a letter? Or is the strength of the documentation in the aggregate? Do text messages reflect the same level of intimate conversation as snail mail correspondence between two people? Or do we approach this differently, in an academic sense, because the individuals who sent those tweets were aware of Twitter’s public nature? And when creating documentaries, is there a better way to fit tweets, Facebook updates, or other public forms of communication into a multimedia narrative?

Vanessa: You pose extremely relevant questions that historians, archivists, and documentarians will have to debate as they begin the process of preserving and drawing on these digital exchanges. At first reading, a casual comment tweeted or posted on Facebook might not hold historical value on its own, but if it sparks a reaction or begins a longer conversation, then those exchanges collectively can tell us something. Perhaps an archivist can comment on how the field is approaching preservation of digital media. As for public versus private exchanges, people are beginning to blur that line already by sharing personal information on public forums. Many would agree we live in a society of Too Much Information!

“Pillows v. Blankets” shows us how the old formats just aren’t going to capture the digital age. But rather than bemoan the passage of one type of storytelling, I’m excited by these possibilities and eager to discuss with my students how their social media activity contributes to the historical record.

Priya: For my part I would be interested to see how we could document an event in the present day using all of this media. What would a documentary about current events look like? While “Pillows v. Blankets” was meant to be a parody, the issues it brought up are issues that should concern historians far beyond those who work in the field of digital history—especially since it impacts our very real work as public historians in years to come.

~ Priya Chhaya is a public historian working for the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the co-editor of the New Views section of History@Work. You can follow her on twitter @priyastoric or through her personal blogthisiswhatcomesnext.com and website www.priyachhaya.com.

~ Vanessa Macias teaches U.S. History at El Paso Community College. She holds an M.A. in History (American West) from the University of New Mexico and an M.A. in Public History from New Mexico State University.

1 comment