Follow the tags

25 June 2019 – Adina Langer

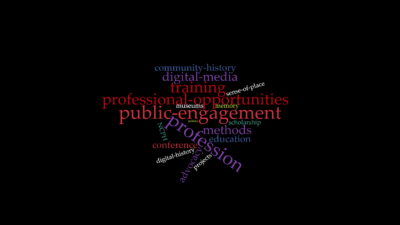

Word cloud showing the most popular “History@Work” tags as of June 2019. Screenshot: Adina Langer

Since we launched History@Work in 2012, we have been thinking seriously about the role of tags in navigating the site and improving our readers’ experiences. Tags are terms related to a post’s content that can be used to link that post in the blog’s back-end database to other posts about similar themes. Before a post goes live on the website, our editorial team selects a set of relevant tags that then appear as clickable links under the by-line on the blog.

Tag-based navigation has a long history within the relatively short history of digital history (try parsing that one three times fast). The photo-sharing website Flickr, founded in 2004, is considered to be the first mainstream Web 2.0 service to make use of tagging and folksonomies to aid both users and visitors in navigating their enormous and ever-growing image database. Museums and archives were also among the earliest adopters of tag-based navigation as a supplement to the controlled vocabularies, such as the Library of Congress Subject Headings, that the latter of which remain the mainstay of professional best practices for thematic categorization in collections databases. I remember drawing inspiration from then-web services manager Sebastian Chan’s innovative work at the Powerhouse Museum in Australia when they were first experimenting with social or user-generated tagging in 2007. However, over a decade out, it appears that the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (the Powerhouse Museum’s parent organization) has dropped public tagging from its website, like most of its peers. During the 2000s and early 2010s, lively debate ensued over the relative benefits of controlled vocabularies (a top-down approach), folksonomies (a bottom-up approach), and some kind of hybrid scheme meant to combine the benefits of professional expertise with the community-driven idiosyncrasies of the folksonomy.

View of the “History@Work” blog website in June 2013 with section categories clearly visible along the menu at top. Screenshot made possible through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. Screenshot: Adina Langer

When History@Work debuted, the editorial team held on to a departmental approach born from our roots in paper publishing and NCPH’s committee structure. We had editorial departments dedicated to the presumably unique interests of consultants, graduate students and new professionals, academics, activists, projects, and international perspectives. When NCPH began making plans for its new institutional website in 2015, the History@Work team took the opportunity to reevaluate its organizational structure under the ever-thoughtful leadership of then-digital media editor Cathy Stanton. Increasingly, the editorial team found crossover and common ground among posts to be the norm rather than the exception. Our “departmental” structure, reflected in a set of top-down “categories” in Word Press, made less sense than it had before. Instead, we realized that tags, which we had already been using in addition to the categories, gave us the flexibility we needed to diversify our outreach and recruiting while maintaining common threads to connect old posts to new. Tags like “training,” “community engagement,” “activism,” and “international” might apply equally well to the work of a consultant, an academic, or a graduate student, or even a graduate student acting as a consultant! Thus, instead of requiring editors to assign posts to a single category (a kind of sorting hat experience) with tags used only for thematic or series linkages, we gave our editors the freedom to assign as many tags as they wanted to a given post, including terms that formerly only existed as categories. Yet, we were concerned about a potential explosion of editor-generated tags if we switched to a fully tag-based approach. Through a series of internal conversations, we enacted an informal tag non-proliferation agreement by which we would train current and future editors to limit the addition of new tags and try to use existing tags wherever possible.

View of the “History@Work” section of the NCPH website in June 2019. Tags appear in pink below the author’s by-line. Screenshot: Adina Langer

Where does that leave us four years later? How useful are the tags we use most frequently? On Memorial Day in 2019, I decided to explore one of our most popular tags, “memory.” Posts tagged with “memory” tend to be reflective in nature, although some deal with specific projects focused on preservation (whether physical or digital). The “memory” tag also encompasses posts about commemorative events, the controversy over Confederate monuments, and the challenges of shaping the memorial landscape within a particular municipality.

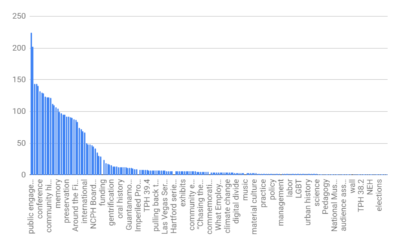

Bar graph showing the exponentially decreasing frequency of use of tags from the most popular to the least popular on “History@Work.” Graphic: Adina Langer

The “memory” tag has been used more than 100 times since the blog began, as have most of our “most popular” tags listed on the right-hand navigation pane of the History@Work landing page. However, of the 314 tags created during History@Work’s lifespan thus far, over half have been used but once, and more than 75% have been used ten times or less. In some cases, limited-use tags are important for documenting unique series linked to a particular conference city or an edition of The Public Historian. But in those other cases, are we creating redundant or unnecessary tags, or is it worthwhile to create new tags whenever an editor feels that a new theme is worth documenting and exploring?

This post was prompted by a recent editorial conversation during which we were using Google Analytics to review our most popular posts, noting how long visitors stayed on the site and what were their points of entry and exit. We wondered to what extent our visitors use tags to jump from one post of interest to another on a similar theme. Google Analytics cannot reveal the intimate details of reader behavior, so we are asking you to help us to better understand how you prefer to navigate within History@Work. How do you use History@Work’s tags, dear reader? How would you like to see us maintaining, expanding, or reducing their usage in the future? Don’t be shy! We thank you for your thoughts.

~Adina Langer has been part of the History@Work editorial team since 2012 and was a writer for the “Off the Wall” blog before that. Her fascination with tags began in graduate school and has not abated in the decade since. You can find her on the web @artiflection and www.artiflection.com.

“Tag non-proliferation agreement.” 🙂

I love that this discussion continues. I really think it’s part and parcel of the never-resolvable “what is public history?” discussion, as well as a reflection of the way that any organization tries to carve out a clearly-defined space for itself in the wider digital environment.

To me the specific tags and their uses are actually less significant than the continued debates about them! But you probably knew that already.

So nice to hear from you, Cathy! We do live on shifting sands, don’t we. #self-reflection #hindsight #wisdom. 🙂