Genealogy from below

14 August 2015 – Paul Knevel

methods, community history, scholarship, international, The Public Historian, genealogy, Jerome de Groot On Genealogy, anthropology

Editor’s note: In “On Genealogy,” a revision of the plenary address delivered in October 2014 at the International Federation for Public History’s conference in Amsterdam, Jerome de Groot argues that widespread popular interest in genealogy, and the availability of mass amounts of information online, challenge established historiography and public history practice. He invites other public historians to contribute to a debate about how we might “investigate, theorize, and interrogate” the implications of this explosion of interest in genealogy. We invited four scholars to contribute to this discussion. Paul Knevel is the second of these scholars. We hope you will post your comments to add to this discussion.

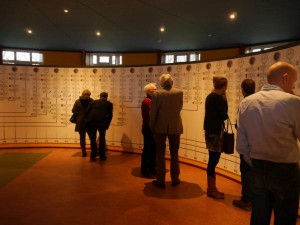

The largest family tree in the world, as claimed by the International Family Museum in Eijsden, the Netherlands. Photo credit: International Museum for Family History

As could be expected by the author of the broad and lucid Consuming History, Jerome de Groot demonstrates in his article in The Public Historian an amazing ability to discuss thoroughly topics and themes that would for others take book-length or even career-length considerations. “Genealogy and Public History” thus not only deals with the various ways that genealogy and family history could be undertaken and imagined by various people and groups but also with such large and profound issues as the impact and construction of “knowledge infrastructures” in a digital age, the silencing character of the archive, the ethical sides of dealing with the dead, the neo-liberalisation of public space generated by commercial websites, “digital labour,” and many other themes and ideas. The result is a clever, multi-layered, insightful, and thought-provoking essay that challenges public historians to rethink today’s digital historical culture and practices, their own role, and the activities of millions of people (see the stunning figures mentioned by De Groot) who are doing genealogy and family history and thus trying to connect themselves with the past. Consequently, it is impossible to address in this short reaction all the topics and themes raised in De Groot’s article.

Instead, in the following, I would like to concentrate on a theme hinted at in various places in the article but not really dealt with: genealogy and family history as a social activity. In his article, De Groot rightfully underlines and clearly demonstrates the necessity for public historians “to recognise, theorise, and understand the various ways in which Genealogy and Family History work, the local, national, and international contexts for such investigation, and the consequences for this practice on the historical imagination.” Not surprisingly, De Groot’s article proves to be an excellent starting-point. He makes many insightful remarks about what it means to do genealogy and family history. But most of his valuable observations and conclusions are not based on “inside” information but on his well-versed knowledge of historiography, cultural studies, digital humanities, and philosophy. The ordinary practitioners of genealogy and family history themselves are remarkably absent in the article: we never hear them talk and reflect in their own words about their own activities, the limits and possibilities of the Internet, the lure of the archive and documentary evidence, their horizon (local, national, international), and their connections with the past.

This view “from above,” so to say, seems to be dominant. In his useful overview of Dutch popular historical culture, A Contemporary Past, the Dutch historian Kees Ribbens, for instance, also deals with genealogy as a historical activity.1 His approach is more down-to-earth than De Groot’s: Ribbens summarizes the history of genealogy in the Netherlands, quickly describes the methodology of doing genealogical research, and writes about the possible motivations of the practitioners. In the end, however, they, the practitioners, are as silent in his study as they are in De Groot’s article.

Whatever the importance of critical reflections and analyses, like the ones presented by De Groot and Ribbens (and they are manifold!), it seems to me as necessary and rewarding to redirect our attention now and then more exclusively to the people whose activities we are studying and dealing with. In our aim to understand the practice and consequences of genealogy and family history, public historians should not only write about the practitioners in the field but also talk with them and listen to them. What I am missing, in other words, is a participatory study of genealogy and family history, a project that starts by studying the various ways that genealogy and family history are undertaken “from below,” by the actual people involved. In a field as rich of local, national, and, thanks to the wonders of the Internet, indeed international organisations, communities, centres and bureaux as genealogy, such research is easily organised at various levels, even as a series of master’s theses. By combining a series of surveys in the tradition of Rosenzweig/Thelen’s The Presence of the Past with more anthropologically based observations, like the ones done by Hilda Kean in her London Stories,2 we could try in more detail to understand the ways in which people are trying to bring the past to the present and how the changes in the technological infrastructure indeed have affected their practices and modes of dealing with and thinking about the past.

I would like to learn more about the affective and emotional dimensions of their activities, about their collaborations and sharing of information or “spirit of volunteerism,” as De Groot calls it, and about their ideas of doing research and thinking about history. How, indeed, is the content design of websites like Who do you think you are? story affecting and influencing their narratives of family history? How does the experience of keeping personal belongings of a family member–a photograph, a ring, a badge, a record–affect the forging of connections between the past and the present in a digitized world?

Such a project (or better: a series of projects) should also encompass genealogist’s activities in and contributions to crowdsourced initiatives, like the recent one organized by the City Archive of Amsterdam around militia registers.3 More than in any other field of history, as De Groot convincingly argues, the interface between “amateur,” “user,” “fan,” and professional and institutional bodies is troubled in the world of genealogy and family history. What that means has still to be analysed, described, and understood fully. By looking critically at the “digital labour” done by volunteers in the various institutional crowdsourced projects, the content and role of what Raphael Samuels once dubbed “unofficial knowledge” come into our view, the kind of information generated by people who see genealogy and family history foremost as a social activity, not as a professional calling. How do people rate these experiences and what are the institutions involved and the professionals working at them really learning (or trying to learn) from the input of practitioners? As such, taking genealogy “from below” seriously could be a fruitful starting-point for a dialogue about what it means to share historical information and knowledge and to try to make the past live in the present. Jerome de Groot is absolutely right: genealogy matters.

~ Paul Knevel is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Humanities, Department of History at the Universiteit van Amsterdam

1 Kees Ribbens, Een eigentijds verleden. Alledaagse historische cultuur in Nederland 1945-2000 (Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2001), 114-117.

2 Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past. Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); Hilda Kean, London Stories. Personal Lives, Public Histories (London: Rivers Oram Press, 2004).

Paul Knevel is correct in stating that the practitioners of genealogy are rather silent in my book on Dutch popular historical culture, A Contemporary Past. But the good news is that more recently Gerben Westerhof, Cor van Halen and I had the opportunity to delve deeper into this popular hobby by developing a questionnaire distributed among 300 genealogists. Our open access article ‘The Meaning of the Past: The Perception and Appreciation of History Among Dutch Genealogists’ analyses the meanings genealogists attach to the past and on the emotions and activities connected to this. It shows many of them are looking for sources of information that reinforce an emotional connectedness to the past. Genealogists, as it turns out, have more interest for ‘past’ in the sense of what is close by and small-scale, and therefore almost directly accessible, than for ‘history’ in the sense of the authorized knowledge from the dominant historical canon. More details can be found in Public History Review: https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/phrj/article/view/205