Keeping the faith: Political cartoons in and out of the archives

09 January 2015 – Cathy Stanton

“I am Charlie” has become the expression of solidarity of people around the world in support of the French weekly newspaper following the January 7, 2015 attack.

Photo credit: Robert Couse-Baker

The killings at the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris this week have prompted a passionate defense around the world of political cartoons as free speech, a form of journalistic expression that exemplifies (and occasionally pushes the boundaries of) a free press’s role as critic and gadfly. In thinking about historical precedents and comparisons for the horrific attack, I’ve been struck by a couple of things.

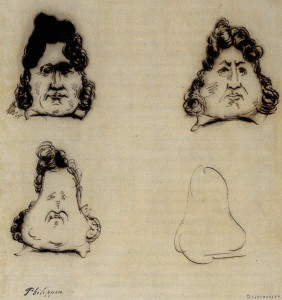

First, historically, cartoonists seem to have been subject to censure and even violence from those in positions of official political power rather than from populist or grass-roots groups. The timeline of political cartoon controversies included in a book on the subject by Victor S. Navasky–himself an experienced boundary-pusher during his long tenure at The Nation–includes many examples of cartoonists persecuted by the powerful (for example, the 1831 trial of Charles Philipon in Paris for caricaturing the French king or the US federal government’s attempts to convict Art Young for his anti-war, anti-capitalist cartoons in 1917 and 1918). Cartoonists have not infrequently butted heads with their own publishers or with the press more generally: Art Young took on (and was sued by) the Associated Press, while Garry Trudeau, creator of Doonesbury, seems to delight in penning storylines that result in his strip being pulled from the newspapers that carry it.

Charles Philipon was put on trial in 1831 for caricaturing the French king, including by showing the monarch’s resemblance to a pear. Photo credit: Wikipedia

But until the 2005 riots following the Danish Jyllands-Posten’s publication of cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammed, there is little evidence in Navasky’s timeline of the kind of non-state religious or ideological violence that has been used in several parts of the world against cartoonists who have provoked the anger of Muslim fundamentalists. What we have seen in the past decade–and in this week’s shootings–seems to be something new. As Tim Wise pointed out in a Facebook commentary (reposted here) after the Paris attack, satirizing groups and people who are often outside the official structures of power carries a different valence, and while satire surely deserves legal protection and murder does not, the dynamic here is more complex than the David and Goliath story of brave cartoonists going up against entrenched elites.

And the second thing that struck me, after some Internet searching for parallels or longer histories, is how embedded historical political cartoons are within the very bosom of the American state that they have so often criticized. From the US Library of Congress’s Herblock collection (and its guidelines for teachers who want to use editorial cartoons in their classrooms) to the National Archive’s Clifford Berryman exhibit and the Dirksen Congressional Center’s Editorial Cartoon Collection, there is a surprising (at least to me) amount of preservation and celebration of the art of skewering those elites. I expect this at Washington, DC’s Newseum or the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco. But to find it in more staid and state-oriented settings (for example, the James Monroe Museum’s Political Cartoons project) seems like a heartening reversal of the long-time tension within the state vs. cartoonist relationship.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that controversial cartoons only find their way into official museum exhibitry when their sting is gone–that is, when they’re no longer really controversial. And there may be other explanations. For example, institutions trying to reach broader audiences may find that cartoons provide an engaging interface.

But even at a supposedly safe distance, that interface can still be a lively place with implications for the importance of what public historians do. Any porous and popular edge of museum and public historical work presents us with opportunities to engage questions that have present-day currency for various publics. And an attack on the basic liberal principles that undergird much of our work may spark new solidarities that remind us of why it matters to protect arenas of civic discourse and the expressions that can happen there.

Wednesday night’s vigil for the murdered journalists held at the Newseum was one instance of that kind of solidarity. In a quieter way, perhaps the collections of political cartoons that have moved from “news” to “history” are also keeping the same faith.

~ Cathy Stanton is a Senior Lecturer in Anthropology at Tufts University and Digital Media Editor for the National Council on Public History.

In the US at least, most newspaper editorial cartoons have long lost their bite and cutting edge political satire. In an age were newspapers are becoming increasingly irrelevant, keeping an editorial cartoonist on staff is a luxury so most are let go or not replaced after the retirement of the old cartoonist. They are then replaced with a syndicated editorial cartoons for a few dollars a pop and allow editorial staff to steer clear of any controversy that may scare off any remaining advertisers. Even South Park and Family Guy are far more edgy than anything coming out of US newspapers these days. I think an expanded definition of “political cartoon” is needed here. Look to online for the real use of cartooning in political satire not newspapers. Most newspaper cartoonists are killed by economics and not by fundamentalist extremists.