Make queerness relevant again

01 March 2017 – David C. White

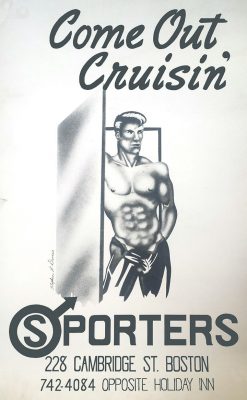

Poster for Sporter’s, one of Boston’s earliest gay bars, c. 1960s. Image credit: William Conrad Collection, The History Project, Boston.

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a series of posts reflecting on Gregory Rosenthal’s article, “Make Roanoke Queer Again: Community History and Urban Change in a Southern City,” published in the February 2017 issue of The Public Historian, and on how the Roanoke project relates to other LGBTQ public history projects.

David C. White is writing on behalf of the History Project, Boston.

Forty years ago, Jonathan Ned Katz published his groundbreaking Gay American History. Based on Katz’s 1973 play, Coming Out!, the book is a collection of primary sources exploring gay life from the colonial era to the present. From the outset, Katz intended for Gay American History to serve one very important purpose: to ground the transformative activism of the 1970s within a historical context. Yet, even as he collected a mountain of evidence to support his thesis, Katz couldn’t help but wonder whether Gay American History was too bold a title—did such a thing really exist?

In the four decades since, Katz and his contemporaries have proven beyond a doubt that not only does gay history exist, but it exists in cities and towns around the world as far back as one can reasonably search. It is found in court documents, private photo albums, and the diaries and memories of older LGBT people who had lived double lives. Inspired by the work of researchers like Katz, community-oriented queer public history programs around the country have spent decades unearthing these stories, effectively putting an end to the pervasive belief that queer people had no social or cultural history.

Reading Gregory Rosenthal’s essay in the latest issue of The Public Historian, “Make Roanoke Queer Again: Community History and Urban Change in a Southern City,” I couldn’t help but think of Katz and his goals for Gay American History. Rosenthal’s essay details their effort to establish and grow the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project in Roanoke, Virginia, and to “preserve our history from ‘queer erasure.’” Following Katz’s lead, Rosenthal grounds Virginia’s LGBT history within a historic context and the larger narrative of urban renewal and gentrification that has shaped present-day Roanoke. But Rosenthal’s attempt to “Make Roanoke Queer Again” is about more than just preventing erasure of Virginia’s queer communities from public memory. It’s also about reviving the spirit of radicalism that’s been tearing down closet doors since the first brick was thrown outside the Stonewall Inn forty-seven years ago.

In many ways, Rosenthal’s essay is a snapshot of the present state of queer public history. From situating LGBT history within a larger social framework to recognizing the need for more diverse representations of queerness, the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project reflects a thoroughly modern, inclusive approach to public history unique to the twenty-first century.

As they led a group on the #MakeRoanokeQueerAgain bar crawl, Rosenthal used oral histories and a 1970s-era bar map to paint a picture of a vibrant, active queer community displaced by urban renewal, gentrification, and heteronormative backlash to the nascent gay rights movement. More than a mere walk down memory lane, the bar crawl acts as an exploration of the various ways in which Roanoke’s gay community resisted oppression. Though they are often overlooked or underappreciated, the bars, baths, and cruising spots are excellent examples of how an uncompromising occupation of public space can act as a powerful means of rebellion. As if it were kismet, Rosenthal’s lesson is emphasized at various points by bar staff asking that they “keep it cool” (read: tone it down), effectively linking civil rights–era intolerance with present-day apprehensions about overt displays of nonconformity.

The group’s future-oriented framework notwithstanding, their efficacy appears to be undermined by a challenge that is neither new nor unique: how to reconcile the present and the past. Although it is an accurate telling of the past, there is an undeniably romantic and nostalgic slant to the #MakeRoanokeQueerAgain bar crawl; a pining for the relatively more exciting social climate of the 1970s over the post-assimilation banality of the present day. Despite the subtle links between the intolerance of the past and assimilation and gentrification of the present, the relevance of the bar crawl, as described, is ultimately overshadowed by the more theatrical elements of the event, including conspicuously queer appearance and a dramatic attempt to reclaim a previously gay space by chanting “We’re queer, we’re here, serve us a drink.” The end result is ostensibly an engagement with the past that feels more like a reenactment of history than its thoughtful application to the present.

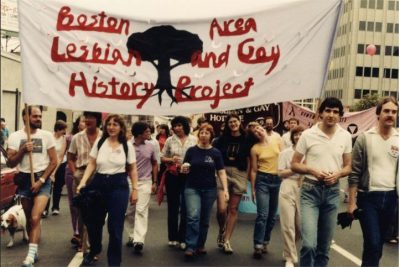

The original members of The History Project, Boston Pride, 1980. Photo credit: The History Project, Boston.

In no way do I want this to be perceived as a criticism of Rosenthal or the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project. Indeed, that I can recognize this with a degree of ease is likely due to my own struggles to make LGBT history relevant in the present and future. As a member of Boston’s History Project, I too am drawn to the concept of space and urban (re)development as a framework for sharing and contextualizing our story. In my time with the History Project, I have attempted to build on our knowledge and understanding of, among other things, Boston’s gay bars, drag performers, and other representations of radical queerness.

The mandate of most public history programs is to engage the audiences in the practical application or understanding of their collective past. It is precisely this that makes LGBT history projects so exciting, complicated, and valuable. At the History Project, we try hard to balance a celebration of the big names and events with a focus on the everyday lives of queer Bostonians, encouraging the latter to see their experiences as equal to those of the former. Through our public lecture series, “Out of the Archives,” we present broad topics such as Boston’s drag history or the South End neighborhood, while also engaging participants in more personal, resonant concepts, such as the ways in which their private photographs represent queer history or how gay pornography helped strengthen social connection in Boston’s gay community. Nevertheless, I wonder whether our current frameworks and approaches are relevant to present-day audiences, or whether they see LGBT history as little more than a momentary exercise in nostalgia.

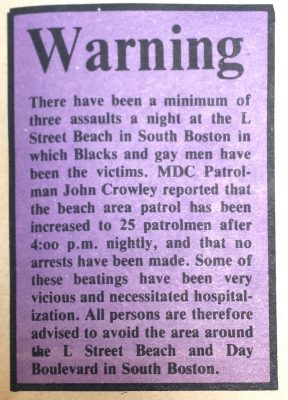

A warning to Boston’s gay community from Gay Community News, c. 1970s. Image credit: The History Project, Boston.

When Jonathan Ned Katz published Gay American History, it was with the intention that his work would strengthen the foundation of a gay rights movement oriented towards a more tolerant future. Ironically, it’s largely the success of that movement for equality and integration that’s made visible, radical queerness nearly obsolete in the twenty-first century. Moreover, the activism and advocacy that we often use to frame our historical narratives was a direct response to the oppressive forces of the era. The problem with making Roanoke (or anywhere else) “queer again” is that it overemphasizes the romantic aspects of the gay rights movement, while overlooking the larger context that created a need for activism in the first place.

None of this seems lost on Rosenthal. Even as they encourage Roanoke’s LGBTQ community to “Make Roanoke Queer Again,” they appear to recognize the discrepancies between the sentimentality of oral histories and the complex realities of our collective past. The history of queer people, before and after Stonewall, is undeniably inspiring, but it is also a story dominated by white men and rife with examples of animus towards lesbians, bisexuals, and trans people, among others. This doesn’t diminish the achievements of those who’ve come before us or the tremendous efforts of the civil rights movement that has consistently moved us closer to equality. It does, however, raise important questions about what our history means to us in the present. If queer history projects are to remain a source of education and empowerment, to be something more than an entertaining time warp, we must find a way to make our history relevant to twenty-first-century audiences.

~ David C. White is an independent historian and researcher whose work focuses on the overlooked or underrepresented aspects of Boston’s queer history, from the turn of the twentieth century to the rise of the gay liberation movement.