Making my thesis work for me

09 October 2014 – Abby Curtin

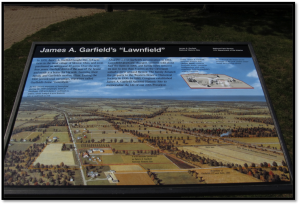

James A. Garfield National Historic Site, the nineteenth-century home of the 20th President, is located in Mentor, Ohio. Photo credit: Andy Curtiss

Currently, public history educators are discussing whether their graduate students should be required to write master’s theses. Although some students (including myself) at times bemoan the thesis as impractical and suggest a public history project or portfolio as an alternative, I found my thesis experience to be integral to my development as a public historian. My research inspired me to reach out to scholars and professionals whose work paralleled my own. It has also opened new doors as I transition out of academia and into a career interpreting the past for public audiences.

My thesis research grew out of my experience volunteering and working as a seasonal interpretive ranger at James A. Garfield National Historic Site, the late nineteenth-century Ohio home of the 20th President. I set out to write about the evolution of the historic landscape of the site, and I wanted to integrate my interest in historic site interpretation into my work, especially because a graduate course on this topic would not be offered during my two years at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). When I heard about the site’s plans to write a new long-range interpretive plan in early 2013, I asked to participate in the process.

The week-long workshop was an outstanding educational experience and opportunity for professional development. I was also able to use the discussions that took place during the planning workshop, as well as the new interpretive plan itself, to propel my argument that the site’s landscape can be used more effectively to communicate interpretive themes. The workshop also shaped my research on the landscape’s history. Staff and volunteers shared their hopes for future interpretation at the site, and I made note of the areas in which they wished to see more research on the Garfield family and their home.

I returned to Indianapolis from the workshop excited and motivated. The staff’s wishes for future research gave me more direction–specifically, I would focus my landscape study on the site’s history as a nineteenth-century farm. I would also incorporate the site’s interpretive goals for the future–including the creation of a self-guided interpretive tool to enhance visitor understanding of the site–into my thesis. Although the majority of my thesis was composed of three vignettes about the history of the Garfield farm, I devoted the last section of my thesis to a discussion of practical applications of my research and the potential for integration of digital technology into interpretation at the site.

In my summer research, which was funded by a grant from the Eppley Institute for Parks and Public Lands, I evaluated what visitors learn about the landscape of the Garfield site from outdoor wayside exhibits like the one pictured here. Photo credit: Abby Curtin

In addition to having the support of staff and volunteers at the Garfield site throughout my research, I was lucky to work with an academic advisor who not only challenged me to produce quality historical scholarship but also supported my desire to incorporate public history into my work. I found that open communication about my goals, as well as my advisor’s expectations, was key in creating a thesis that fulfilled the requirements of the history department and fit my own interests.

Perhaps most surprising to me was the way in which my thesis served as an avenue through which to network with others in the field. With a bit of luck and the willingness to reach out, ask questions, and talk about my research, I came into contact with a number of public historians whose insights and scholarship guided or inspired my own work. I used Twitter to connect with fellow history students with similar research projects and became addicted to reading blogs by other public historians with interest in cultural landscape studies. When I attended NCPH conferences in Ottawa and Monterey, I had the opportunity to engage with these individuals in person.

Keeping questions about interpretation and ideas about practical applications of my research at the center of my thesis work has also opened doors that form the building blocks of my professional career. In the spring of 2014, I was awarded a grant from the Eppley Institute for Parks and Public Lands to conduct interpretation research at James A. Garfield National Historic Site. This funding has given me the opportunity to take my thesis research to the next level. I spent this summer observing visitor behavior and interviewing guests at the historic site about how current exhibits and interpretive tools impact their understanding of the historic landscape. Although I successfully defended my thesis in April, this grant project allowed me to engage my research in new ways. In this regard, my thesis was the catalyst for my first post-grad school professional project.

Researching and writing a thesis was no doubt difficult, but I found the process to be exciting, catalytic, and instrumental in my development as a public historian. It was especially rewarding to witness my thesis research propelling me towards new opportunities in the field. As I continue to build my career, I can hold up my thesis as an example of my ability to not only conduct thorough research and write a critical historical interpretation but also express vision for new ways to present the stories of the past to public audiences.

I hope that students of public history will see writing a thesis as an opportunity for exploration rather than an impediment in their quest for an advanced degree in public history. I found many opportunities to engage with public history professionals, think creatively, and present fresh perspectives on my topic while writing my thesis, and I know several classmates who are having similar experiences. When viewed as an opportunity, rather than a hurdle in the public history curriculum, a thesis can provide the chance to devote oneself to a topic about which one is truly passionate.

~ Abby Curtin earned her MA in public history at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis in 2014. She currently works at Cleveland Restoration Society.

Thanks for this post. My plan is to work on a project rather than a thesis, but I may–based on this post–talk to my grad director about the options. I’ve already sent him this post.

Thanks for your comment, Barbara. I think the main takeaway from my experience was that no matter what the requirement, a thesis, project, or portfolio, students should look at it not as a major obstacle, but an opportunity for exploration. Good luck with your project!

What a fantastic and insightful perspective on writing one’s thesis in this field. Viewed as not only a dreaded task but an opportunity for life long learning!

Howdy my #NCPH2014 mentee! Great work in discussing your thesis and its practical use.

I am one wholeheartedly in thesis camp on the thesis vs. project divide. Life is full of projects and a good public history degree program should have many of them in the curriculum. But one thing that sets the history field (and by extension the humanities fields) apart is our devotion to the thesis/dissertation model as the culminating event in graduate school.

I find a lot more in common with folks who have that shared experience and lean more towards interns and applicants who have completed that exercise because they (you) have shown an ability to work on something big, on your own timeline, while still juggling your life/work.

This is a critical function of life within, but more importantly outside of, the academy. It is often one stumbling block for students because we are so much on our own as we complete the project.

All in all, I think you will find yourself much better prepared by having completed this crucial step in graduate school, thank going the project route.

Hi Bob! Thanks for your comments. I wholeheartedly [in retrospect] agree. I look forward to seeing where my experience takes me in the future!