Meeting our audiences where they are in the digital age

30 March 2016 – David Hochfelder

"Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology" responses, public engagement, community history, digital history, The Public Historian, TPH 38.1, digital divide

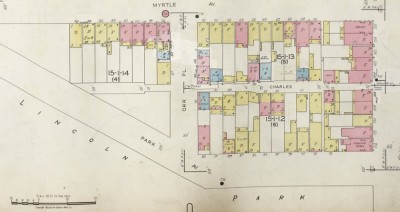

Image from the 98 Acres in Albany digital project.

By 1960, about 15 percent of the South Mall take area’s 7,000 residents were African American. James C. Strawn was a janitor, musician, and off-the-books barber who moved into the South Mall take area soon after World War II. Mr. Strawn told a Knickerbocker News reporter that he hoped that “tearing down these 50- and 60-year-old buildings might make for some decent places in which to live.” Courtesy New York State Archives.

In his article, “Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology: Public History Meets the Digital Divide,” Andrew Hurley does the public history community a great service. He does more than tell us a cautionary tale about rushing headlong into digital approaches to public history and leaving target audiences behind. He provides a clear-headed analysis of why a gap between platform and audience can exist, and he suggests steps that can bridge that gap. His analysis is all the more valuable, given that many similar projects will come online in the next few years. While the digital access divide of the 1990s may no longer exist, Hurley reminds us that socioeconomic status, race, and age still shape how users interact with digital technology—and that public historians must take this into account in our work.

Hurley reminds us that, as public historians, we need to meet our audience where it is, and not where we would like it to be. Hurley also shows that digital technologies can work well when integrated with more traditional public history outreach efforts. But digital innovation cannot be an end in itself. These are lessons that we would do well to remember.

One issue is the short half-life of digital platforms. In a world of frequent browser and operating system updates, a website that functions well in 2016 will likely have diminished functionality in 2020. For example, a website published in 2007 will probably not work very well on a mobile device today. Unless we devote resources to maintaining and updating our digital projects, they will become archaic or, worse, nonfunctional within a decade.

Another consideration is funding. Many grant opportunities (NEH digital humanities opportunities, for example) give great weight to digital innovation. Such requirements make it unlikely that a project will obtain the necessary funding unless it can promise to develop and deploy new digital tools and techniques. So the funding process often builds in a gap between medium and audience from a project’s very inception.

As Hurley shows, the most pressing concern is to meet our audiences where they are. As his Virtual City Project demonstrates, inner-city, low-income, and elderly populations will not have the digital literacy to exploit the latest techniques and tools. We must therefore shape our projects to suit the needs and capabilities of our audiences.

Governor Nelson Rockefeller and Jennie Scanese of 161 Hamilton St, July 11, 1962, as demolition of the area that would become the Empire State Plaza began. Photograph by Bob Paley, Albany Knickerbocker News. Used by permission of the Albany Times Union.

I have some limited experience with the issues that Hurley outlines. I am working with a team on a project similar to his, a website that will digitally reconstruct and repopulate a 98-acre area of downtown Albany, New York, demolished in 1962 for a futuristic state capitol complex. The Empire State Plaza remains controversial fifty years later. One of the major goals of the project is to facilitate a more informed conversation about the costs and benefits of urban renewal.

When I describe our project to historians, they often ask if we plan to use augmented reality, gamification, or 3D walkthroughs. Those technologies sound exciting and innovative, but I expect that we would lose a lot of our audience if we adopted the latest digital platforms. Like Hurley’s Virtual City project, ours relies on a mix of archival research, oral history, and collection of family photographs and other ephemera. We try, as Michael Frisch famously phrased it, to create a “shared authority” that gives full voice and participation to former residents and business owners. Many of the people we have interviewed are elderly and are not conversant with the latest digital technologies. Many do not own smartphones. In our experience, they are familiar with the basics—e-mail, scans of photographs, and two-dimensional maps.

Sanborn map detail showing the home of Jim and Emma Leonard at the southern edge of the take area, corner of Park Avenue and Orr Place. The Leonard family was the last to leave the South Mall take area. Read about their story here. Used by permission of the Sanborn Library, LLC.

This awareness of our audience has shaped our publication and outreach strategies. We plan to digitally reconstruct and repopulate the 98-acre “take area” by using a Sanborn fire insurance map as our interface. As we presently envision the interface, users will be able to click on a particular building on the map and pull up photographs of the structure, along with information such as the number of apartments, year built, names of the residents, owner’s name, etc. While we are using a GIS platform and will georeference all the structures shown on the Sanborn map, we will almost certainly not build a three-dimensional or augmented reality recreation of the era. Our audience does not call for this level of sophistication, and doing so would likely increase the project’s cost.

Our outreach strategy also begins with an awareness of our audience’s digital skills and capabilities. We have been publishing preliminary findings in the form of photo-essays on a WordPress blog. We publicize these posts through Facebook and Twitter feeds. When the opportunity arises, we present our work in the local media. One such opportunity occurred this past summer, when the State of New York celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the cornerstone-laying ceremony. We responded with a guest editorial in the Albany Times Union, two appearances on WNYT Channel 13 news, and a piece on the take area’s demographics that appeared in a popular news and entertainment blog.

As more of us develop digital and spatial history projects, it is important for us to keep focused on the considerations Hurley raises. As he eloquently frames the issue, “it is worth asking whether the technology has improved public history’s capacity to achieve one of its central goals, the animation of enlightened civic activism.” We ought to keep this at the center or our public history work, no matter how sophisticated our tools become.

~ David Hochfelder is associate professor of history at University at Albany SUNY. He served as associate director and director of the Public History MA program from 2010 to 2014.

Editor’s note: In “Chasing the Frontiers of Digital Technology,” published in The Public Historian (38.1), Andrew Hurley discusses the implications of the digital divide when working with diverse audiences and striving for public engagement. This is the third of five posts that will be published digitally by The Public Historian responding to Hurley’s article.