Where is the next generation of gender studies in public history?

09 August 2013 – Cathy Stanton

Lowell National Historical Park’s interpretation of women’s industrial labor, as reflected in this model of an integrated textile mill, remains ground-breaking after 35 years.

When I was first invited to accompany the tour as a kind of traveling-scholar-in-residence, my first thought was, “But I don’t do gender in my work.” That was quickly followed by the realization that in a world inflected by feminist and queer scholarship and activism, most of us do indeed do gender, at least implicitly, whenever we think about interpreting the past in public. Like race and class, it’s become something that we automatically tend to ask ourselves about. It’s a crucial way to pry open received histories and connect to present-day concerns. And the question that I found myself returning to as we visited museums, historic houses, a textile mill, a ship, a college campus, a settlement house, and a cemetery or two, was, “Is there a new interpretive landscape beginning to take shape now that we’ve made gender a more central part of public historical inquiry?”

If there is, it’s probably most visible and vibrant in the interpretation of queer histories, a field just beginning to find itself and develop conventions of museological display. (Julia Brock’s pieces here earlier this year, showcasing the work of John Q and E.G. Crichton, along with Hugh Ryan’s recent piece on the Pop-up Museum of Queer History, point toward some emerging practices in those areas.) The performativity and genre-busting qualities of some of this new work wasn’t really present in the one site we visited that incorporated some focus on sexuality—the Sleeper-McCann house in Gloucester, home of gay interior designer and collector Henry Davis Sleeper—but it is definitely pushing the edges of the newer literature on queer and LGBT pasts.

In general, though, what I found as we toured the various sites—and even moreso when I surveyed the available scholarship—is that to a very large extent, what’s being said and done in public history interpretation of gender and sexuality remains firmly within the model of adding neglected or “subaltern” histories into mainstream or “official” narratives. Gender itself as a category of identity wasn’t really being interrogated at any of the places we visited, in the way that feminist and queer scholarship have been interrogating it for two or three decades now, and that reliance on older patterns seems to be reflected in our disciplinary scholarship as well.

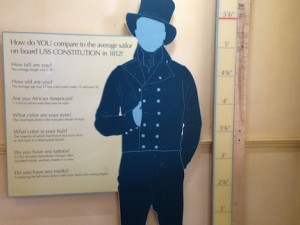

The gender of Boston’s 19th century sailors goes unremarked in this panel at the USS Constitution Museum in Boston.

There are lots of institutional, financial, and other reasons why museum exhibits and other kinds of interpretation change slowly, of course. I’m writing this not to find fault but rather to invite public historians to think about whether we’ve reached a point where just adding in the “subalterns” is no longer enough.

Tour participants survey the due-to-be-refurbished display on MIT’s first woman graduate and faculty member Ellen Swallow Richards.

But maybe the next step has to involve some kind of challenge to these “received” and always problematic categories of identity themselves—white, black, male, female, gay, straight. I came away from the tour thinking that if that’s the case, we’re still just at the very beginning of a paradigm shift away from interpretive patterns associated more with the activism and scholarship of the civil rights era, second-wave feminism, and first-generation gay activism. I’m interested to hear what others—particularly younger practitioners—have to say about this. What does the emerging landscape of gender and sexuality interpretation look like to you?

~ Cathy Stanton is a Senior Lecturer in the Anthropology Department at Tufts University and the Digital Media Editor for the National Council on Public History. Photos are by the author.

Hello,

I stumbled upon your article via a professor I had at the University of Minnesota-Morris, Dr. Elaine Nelson. I am currently a sophomore at the University, and I hold an internship with my local Historical Society, The Bloomington Historical Society in Bloomington, MN. I have finished a World War One project and currently working on a WWII project. Both of which I have and plan on including the roles of women either in armed forces or on the home front. However, due to the lack of funding that many small historical societies have, it is hard to capture each facet, especially those of which are just gaining ground in our society. I feel as though larger county, state or private historical societies may have a better opportunity to at least touch on the less mainstream topics such as gender and sexuality. All in all, I hope one day our society will improve upon itself and discuss the less common aspects of history.

I know that the American Association for State and Local History, an important resource for smaller history institutions and sites, is producing a handbook on interpreting LGBT history, so that may be a useful resource for places that don’t have a lot of funding but that might want to expand the range of stories they’re telling. It’s often a matter of taking a different approach to your existing collections and narratives, rather than adding in something completely new!

I was very excited to see this question posed. I happen to be finishing a PhD in public history using the history of sexuality as a second field. I decided that the two could be reconciled when, in 2010, I browsed through past NCPH programs and found only a handful of presenters dealing with issues of sexuality. Clearly, this is a gap in our field, which is slowly being filled by the momentum of projects emphasizing LGBT history. But, as you comment, this is often a restorative history focusing on activism.

To me, public historians may “do” the history of sexuality in a number of important, potentially paradigm changing ways. The use of oral history has been widely successful in the understanding of “subaltern” histories (the Queer Twin Cities OHP comes to mind), revealing vibrant sources obscured traditional documentation.

How does sexuality become encoded on the landscape? Many of the first influential studies on sexuality were locality-specific; New York, Fire Island, San Francisco. This is a question that preservationists and cultural resources managers must debate as LGBT/queer history becomes integrated.

Finally, there is more work to be done exploring the links between race and sexuality; from better understanding the experiences of African American individuals across time to deconstructing how a particular version white heterosexuality came to be valorized in the twentieth century.

I write this just having learned that Showtime is producing a drama about the lives of sexologists Masters and Johnson, so if popular culture is any barometer of a wider interest in sexuality, then now is the time to grapple with these issues.

Best,

Elizabeth (Middle Tennessee State University)

In some ways “just add minorities and stir” is easier – both for public historians to do and for audience to grasp. To challenge problematic categories of identity themselves, as you suggest, is a lot harder, both conceptually and politically. For several years an exhibition that deconstructs race, developed by The American Anthropological Association, has been travelling the country. Would be interesting to consider how it has addressed the questions you have posed. (How) do audiences respond? See: http://www.understandingrace.org/about/tour.html