Mapping Dissent: Queer and Trans resistance at UCSB

09 July 2019 – Melissa Barthelemy

art, LGBTQ history, methods, social justice, public engagement, TPH 41.2, media, speech, graduate students, The Public Historian, gender/sexuality, gender

“Mapping Dissent” participants walking across UCSB campus holding testimonial signs and sledgehammers for installation. Photo credit: Bennett Barthelemy

Editors’ Note: This post is one of two History@Work pieces inspired by the current special issue of The Public Historian: “Queering Public History,” Vol. 41, No. 2. You can read additional LGBTQ reports from the field in this NCPH ePublication, which complements The Public Historian issue and these blog posts.

For many of us in the queer and trans communities, the election of Donald J. Trump as President of the United States made us feel like our hearts were ripped from our chests and stomped on. That pain has only increased with each passing month of the administration as more insults, hatred, and discrimination are foisted upon the queer and trans communities as well as other marginalized populations in our country and beyond.[1] In the wake of this current political reality, many have engaged in acts of resistance, solidarity, and coalition building. I was able to take part in such an effort in April 2017 at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I am a PhD Candidate in Public History.

Three students work together to pound sign with testimony into the lawn in front of Storke Tower on the UCSB campus. Photo credit: Bennett Barthelemy

Queer feminist and Mexico-City based artist Lorena Wolffer staged Mapping Dissent, a participatory cultural intervention centered on marking UC Santa Barbara with queer affective[2] responses to the presidential election and its aftermath. The project entailed the collection of resident’s testimonies that spoke to the situation by students, staff, and faculty at UCSB, and community members from the Santa Barbara area, which were placed on campus in the form of street signs during a collective walk in April 2017. The testimonies were then read aloud at the base of Storke Tower, a prominent free speech zone[3] on our campus. Jennifer Tyburczy PhD, a professor in the Feminist Studies Department, facilitated the project at UCSB in collaboration with Wolffer. The intervention involved the participation of over 30 students, staff, faculty and community members. I served as a facilitator and installation coordinator for the project.[4]

A particularly powerful testimony was written by a 20-year-old queer student named Jaime. They wrote: “November 8: The day I realized that we really hadn’t left the closet. The world had shoved us back in. Then set fire to it.” This testimony encapsulates so much of the pain, fear, and anger that many of us are experiencing. It viscerally conveys the violence and terror inflicted on queer and trans bodies.

Another testimony by H.K., 26, art historian, said: “So much has changed. Nothing has changed. We are less safe than we have ever been in our lifetimes. We have never been safe before. We are rising to new resistances; we have always been resisting. This is Trump’s America. This is just America.”

This project was about giving voice, taking up public space, and disrupting the everyday. We dressed in solid black and remained silent during the performance; we moved as one. As we walked across campus as a group, it required that we stop the flow of bicyclists on the bike paths and that we temporarily take over sidewalks. In that moment as a body—both individual and collective—we were undisciplined, uncompliant, and unwilling to submit to the expected paths, borders, and flows that regulate daily existence on our campus. We were using sledgehammers to loudly pound stakes with signs into the ground, and these efforts required teamwork and coordination. As a group we were not interested in “passing” as our non-normative bodies—queer, trans, and allies—directly intervened in the campus patterns of movement and behavior that are assumed and expected.

MAPPING DISSENT allowed queer and trans community members to validate their emotions and foster LGBTQ community solidarity as well as increase dialogue with those who identify as heterosexual and cis-gendered.[5] I had an opportunity to interview Wolffer and find out more about her thought process behind the intervention. I asked her about the role of emotion in these testimonies. She said, “I think especially when it comes to political situations or political data we are very used to addressing it through objective reason, and then reasoning our way through what we think about it and how we view it. But, I think it is very different to ask people to voice their feelings. We all have very emotional ways of addressing and responding to political situations but we are not used to talking about them.” Participants who collected testimonies spoke about the initial challenges of getting informants to enunciate and elaborate on their feelings since most people are used to just using words such as “sadness,” and “anger.”

Providing marginalized folks an outlet to voice their feelings with each other and the public brought people together in a way that wouldn’t have happened through merely an objective analysis of the situation. Undergraduate students I spoke with at the time described the intervention as “powerful,” “healing,” and “personally transformative.” Students spoke about the importance of having faculty and staff engage in a project with them outside the classroom that was so deeply personal and meaningful.

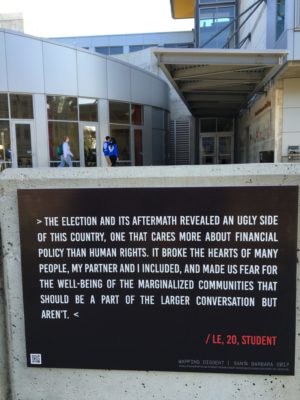

Sign with testimony affixed to a wall in front of Student Resource Building on the UCSB campus. Photo credit: Melissa Barthelemy

According to Wolffer, “for queer people, the way that we feel is constantly called into question, to begin with, whether what we feel is valid, whether the feelings we have towards each other are valid, whether these feelings should have a place in legislation.” She says that interventions like Mapping Dissent bring in the queer perspective of people whose feelings have been repeatedly denied.

So much of the Trump presidency has exposed the deep ugly underbelly of American politics and history, legacies of discrimination and violence, as well as greed and corruption. This is not new, and yet there is such a brash amplification that it is harder for even those who usually sit in seats of privilege to ignore. His racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic rhetoric and policies, as well as his ableism are on full display for the nation and the world. If there is a small sliver of a silver lining to any of this, it is that some people are waking up to see and better understand the oppressions that minoritized populations have endured for centuries.

We know that to a certain extent our universities are a microcosm of society and what is going on in the country is reflected on our campuses. Controversies over speech and the utilization of public space on college campuses are ultimately about power. Much of the national discourse around free speech controversies centers around protecting heterosexual white male fragility and privilege by ignoring the corporeal realities of our lived experiences.[6] It is easy to focus on words and speech in the abstract but we all inhabit bodies, some of which are more closely monitored and punished than others, and often with deadly consequences. We must be willing to challenge the underlying structures, policies, and beliefs that allow homophobia, transphobia, and other forms of oppression to flourish on campuses and in society. We must resist.

~Melissa Barthelemy, JD, MA, is a doctoral candidate in public history at the University of California, Santa Barbara and an intern to the Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs. She is also a UC Free Speech Fellow for the UC National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement.

This blog post is dedicated in the memory of Francine Ramirez, a UCSB student and MAPPING DISSENT community member who we lost on February 11, 2018. Rest in Power.

[1] The HRC cataloged the Trump/Pence attitudes on LGBTQ+ rights.

[2] Google Dictionary defines “affect theory” as a theory that seeks to organize affects, sometimes used interchangeably with emotions, or subjectively experienced feelings, into discrete categories and to typify their physiological, social, interpersonal, and internalized manifestations.

[3] It is an area where amplified sound is permitted, and where students and others are generally able to hang signs without needing prior approval and where people can often congregate more spontaneously (i.e. solidarity vigils, protest marches). The policy is stated on a UCSB website.

[4] Mapping Dissent Project Booklet, University of California, Santa Barbara 04_2017, Wolffer conceived the intervention for the Queer Hemispheres Radical Performance Series as part of her ongoing project Afectxs ciudadanxs/Citizen Affects, MAPPING DISSENT.

[5] The phrase cis-gendered refers to a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex.

[6] The “corporeal realities of our lived experiences” means that Queer, Trans, and People of Color (and those who are QTPOC meaning Queer and Trans People of Color) suffer discrimination and often physical harm based on their bodies—the way their bodies present racially, and in terms of sexual orientation and/or gender. Hate crimes against the Trans Community, in particular, have been on the rise in recent years. See Human Rights Campaign, “Violence Against the Transgender Community in 2018” and John Eligon, New York Times, “Hate Crimes Increase for the Third Consecutive Year, FBI Reports” November 13, 2018.

Thank you Melissa for sharing such an insightful piece that sheds the light of truth.