Revisiting Monterey 20 years after "The Politics of Public Memory"

14 January 2014 – Martha Norkunas

Norkunas’s 1993 book was an early contribution to the literature focusing on silence, history, and power.

When I was researching the The Politics of Public Memory: Tourism, History, and Ethnicity in Monterey, California (State University of New York Press, 1993) in the late 1980s, I was deeply affected by the disparity between the haves and have-nots in Monterey. Nearly every day I saw Jaguars, BMWs, and Mercedes on the streets, and from time to time I saw a Rolls Royce. Pebble Beach and Carmel (and the then-mayor of Carmel, Clint Eastwood) joined with Monterey to create an atmosphere of wealth: old wealth, new wealth, and the wealth of those who knew great places in the world.

Where, I wondered, did the workers live? How could they afford an apartment anywhere near their places of work? Who lived in Monterey? Who once lived there? I could see that many of the workers were of Mexican or Latin American heritage. I knew there had once been a significant Chinese population on the peninsula, that Native peoples lived there, that African Americans lived in the area, and that there were other ethnic and cultural groups in the past and present.

Many of Monterey’s historic working-class spaces have been reconfigured as sites of upscale consumption. Photo credit: JimG.

I grew up with an acute sense of ethnic and class identity so I was particularly sensitive to both as I explored Monterey. I toured the historic sites in the city and was struck by what was missing: any meaningful discussion, or any discussion at all, of non-white, non-elite people. Where were interpretations of the working classes, the poor, the migrant workers? How did all of these different ethnic groups and social classes fit into the complex puzzle of the peninsula? Most importantly, why were they omitted from the historic landscape of the area?

This is when I discovered the power of silence. The Politics of Public Memory was published two years before Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s masterful Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Beacon Press, 1995); both are early works in silence, history, and power. (For a public historian’s reflections on Trouillot’s book, see this 2012 post.) As I explored the city, I saw how normalized silence had become. People of Mexican origins were associated primarily with music and dance, the Native peoples were shown as anthropological, the Chinese were nearly non-existent, women marginalized, and other ethnic groups eliminated entirely. Class issues, so evident in the performance of everyday life, vanished from discussions of the past. It seemed to me then, as it does now, that eliminating groups from the past, and normalizing that exclusion, impacts their access to power and resources in the present. It is not benign. It has real consequences.

This insight has become nearly commonplace in the twenty years since the book was published, yet the practice of exclusion at historic and tourist sites is still so widespread that I could go to any state in the nation and write a similar book today. People of color—an identity that varies from place to place—are still notably absent. Working-class people, the working poor, even lower- and middle-class people, are not well represented at historic sites. Many sites shy away from any class references, preferring to create a composite portrait of “the people” who once lived in an area. But “the people” are normalized as upper-class whites.

On a recent tour of The Hermitage, President Andrew Jackson’s home in Tennessee, I heard the costumed docent explain to visitors that, “anyone who came to the front door of Andrew Jackson’s home was welcome.” In a simple phrase she normalized “anyone” to mean a person of wealth, status, and European descent, yet no one questioned her. Would, I wanted to ask, a person of African descent or a Native person be “welcomed” as a guest at Jackson’s front door? In sites all over Texas and Tennessee, the two states whose historic sites I am most familiar with, people of color, women, and the middle and working classes and the poor are still systematically excluded from interpretations of the past. With the insightful, brilliantly researched texts that have explored power, history, and class, it is difficult to imagine how historic sites can remain so entrenched in the stories of the American elite, yet they do.

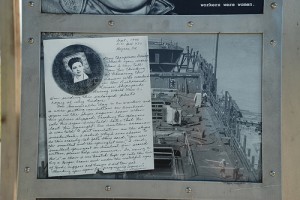

Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California, does foreground women’s and workers’ experiences. Photo credit: Russell Mondy.

Certainly there are outstanding examples of historic sites that have meaningfully interpreted women, people of color, and the poor and working classes. The Lowell National Historical Park is one such example, and there are other national park sites that have changed their approach to the past in response to ideas of civic engagement and post-conflict studies. There is a National Museum of the American Indian and a soon-to-be opened National Museum of African American History and Culture. The Lower East Side Tenement Museum, the Memphis Civil Rights Museum, Women’s Rights National Historical Park, Rosie the Riveter Park in California, Boston’s monument to A. Philip Randolph and the African American Railroad Workers, Robert Gould Shaw/54th Massachusetts Infantry Memorial, a statue to Phillis Wheatley, the ethnic museums in cities around the country, and many African American museums and historic houses: there are many sites that set examples nationally. There are sites of reconciliation, sites of conscience, sites where responsibility for human rights violations are interpreted and debated. Public historians have changed interpretations of the past so that they are more diverse, more complex, and more inclusive of the people who lived in this country. Yet much of the interpretive landscape of memory still valorizes elites of European descent.

I visited Monterey several times since the publication of The Politics of Public Memory. I was gratified to see that there were examples of worker housing on Cannery Row and that the exhibits in the principal history museum have been redone. There were new waysides, new areas to explore. Yet, as in many other places, it seemed that the fundamental script—that of wealth equaling historic status—still dominated. It has been ten years since I’ve been to Monterey. Perhaps things have changed. I hope so, for historians in places of wealth have a unique opportunity to influence elite conceptions of who matters in the past and in the present.

~ Martha Norkunas is a Professor of Oral and Public History in the Public History Program at Middle Tennessee State University.