Adapting and finding meaning in uncertain times: teaching the JOTPY Archive

24 September 2020 – Juilee Decker and Cheryl Jiménez Frei

Editors’ Note: This is the second of three essays about the COVID-19 collaborative archiving project A Journal of the Plague Year: The COVID-19 Archive. The first essay introduces the project. The next will address issues related to archival silences.

Faculty everywhere struggled when COVID-19 resulted in most of us having to teach online. We re-worked syllabi and overcame the Sisyphean task of re-inventing our courses midstream. In particular, each of us had to take our onsite, hands-on, project-based courses and adapt them for asynchronous, disparate learning environments. We faced the challenge of how to make our onsite public history courses work remotely without the thoughtfulness required to design an intentional online course. Teaching the Journal of the Plague Year (JOTPY) archive last spring helped our students gain field experience and encouraged our entire classroom community to understand what historians do, how archives inform the writing of history, and ultimately how stories are told. These are our reflections about what we learned and what we are taking with us to the fall semester.

Juilee’s Perspective: Teaching an upper-level general education, project-based course at Rochester Institute of Technology

After COVID-19 truncated the projects planned for my visitor engagement and museum technologies class, I wanted students to have digital experiences that met them where they were—geographically, technologically, emotionally, and socially. Enter the JOTPY archive!

Students reviewed the JOTPY site and, in turn, contributed five items and associated metadata that embodied their COVID-19 experience to the crowdsourced archive. (The assignment prompt is available as pdf and Word documents.) They enjoyed looking at the entries and seeing how others had characterized their experiences. With its short-form descriptions and inability to comment, JOTPY was unlike the politicized dregs of social media or the ego-deflating viral trends of TikTok. Rather, it offered useful, visual, short-form documentary narratives of life during the pandemic, a historic event that the students themselves—and all of us—were also experiencing.

One of the Omeka items created by Koda Drake, a student in Juilee Decker’s course explained the need for a wrist brace: “I sprained both of my wrists from the increased amount of work and typing I am doing on the computer after all of my classes were moved online. Of the open stores, there was one wrist brace available. I wear it on the wrist that hurts more.” Koda Drake, “Sprained wrist,” April 11, 2020, JOTPY Archive.

The archive afforded me the opportunity to reach the educational outcomes of my course, but in an entirely different manner than I had anticipated. Shifting gears—away from our three well-defined projects into the nebulous space of plan-as-we go where I, too, was learning-by-doing—enabled me to bring my students into the archive community with me. Teaching with the archive gave students the opportunity to do hands-on work, to curate their own lives intentionally, and to write for the public in a thoughtful, compassionate manner. During the project and after the fact, students acknowledged the archive’s historical value, commenting upon its unique ability to document a range of experiences from traumatic and fearful to joyful and productive. Viewing the archive, creating content for it, and reflecting upon the experience enabled each of them to find community within the archive. One student went so far as to characterize the archive’s value as empathetic as well as documentary.

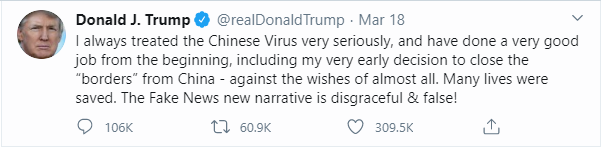

One of the Omeka items created by an international student in Juilee Decker’s course explained concerns about being the target of anti-Chinese sentiment as a result of sentiments expressed on social media. The student who posted this item stated, “I always look through different social media to be aware of anything that might affect me as an international student from China. Donald Trump’s twitter is one of them, and there are multiple posts from him using the term ‘Chinese Virus’ which worry me.” “Trump Used ‘Chinese Virus’ on His Social Media,” March 18, 2020, JOTPY Archive.

Cheryl’s Perspective: Incorporating the Archive in a public history seminar and lower-level survey courses at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

Like Juliee, in the spring, I found myself with students in the middle of a field project that, no matter how I reconfigured, simply could not work online. To their immense credit, when I proposed we shift completely to join JOTPY’s Oral History Project, they dove in without skipping a beat. The students—who after leaving campus returned to towns across Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, and even South Dakota—recorded oral histories and collected artifacts for the archive, documenting experiences of the pandemic in rural communities.

Many had not conducted oral histories before, but as the interviews stacked up, it was clear they had done well. Conducting their first interview with a family member or friend was a good strategy to get comfortable. Beyond this, there was a connection that is less common in many oral histories because, in this case, the interviewers were living through the same pandemic they were asking their subjects about. This lent a level of empathy and connection, as students related to interviewees and asked thoughtful follow-ups. Reflecting on their work, most also noted that conducting interviews over Zoom (a necessity that itself exemplifies our current moment) was more comfortable for them—something I had not expected. In an imperfect situation, JOTPY provided a perfect opportunity for students to respond to history happening in real time, and continue to gain experience in the field.

For my public history students, working with JOTPY seemed like a good fit. As one graduate students said, “it seems like our duty as historians to document what is happening.” Others said the project gave them a sense they were contributing something meaningful when most of us felt helpless. But I was also teaching a Latin American history survey, and I wondered about integrating the archive there. In such unprecedented times, why not allow more students an opportunity to reflect on their experiences? Could this be meaningful for a survey course?

For this, a colleague and I developed an assignment: “Documenting Your Experiences: Creating a Primary Source.” The assignment was two-fold. First, we addressed the need for our majority non-history majors to better understand what a primary source is and why historians use them. Second, our “un-essay” approach gave otherwise stressed-out students broad freedom to be creative in their expressions and encouraged them to donate their sources to the archive. Students also reflected on how their sources will help future historians understand the pandemic. This assignment (available as a pdf and Word documents) could easily be adapted for K-12 students, as teachers and librarians in our community are currently doing.

The result was students responding in incredibly innovative ways. Students created collages, comics, short films, cross-stitches, photo journals, written journals, video logs, and even expressed the rollercoaster of the news cycle and their emotions through piano arrangements.

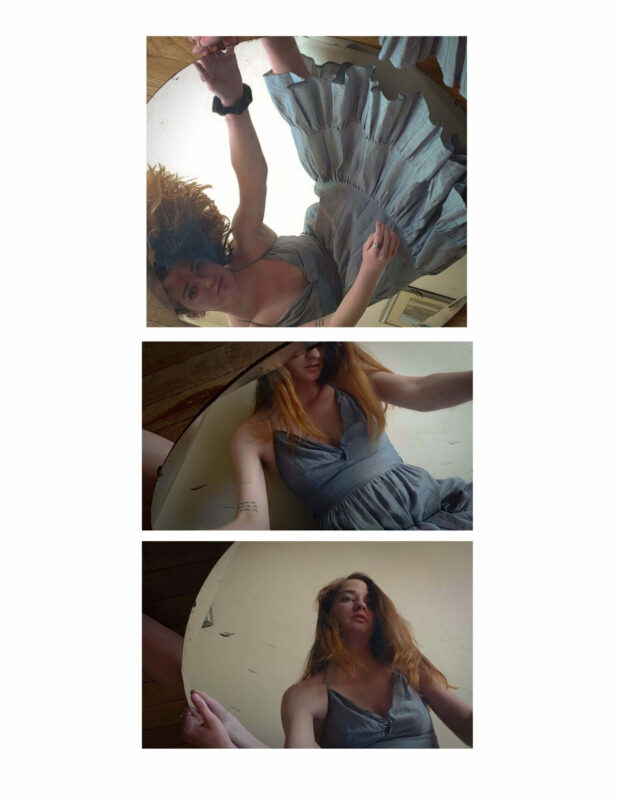

For this anonymously donated photo journal, a student in Cheryl’s Jiménez Frei’s course explained their self-portraits as expressing the disorientation, isolation, and self-reflection spurred by leaving campus and being in quarantine: “I chose to do self-portraits because I thought it was an obvious nod to being in isolation away from family and friends. I also used a mirror . . . to reflect my time in quarantine and the immense amount of time I’m stuck in my own head recently. I’ve had a lot of time to reflect on what I want in the future and what I’ve done in the past.” “Quarantine self-portraits,” May 20, 2020, JOTPY Archive.

Some used the assignment to express raw, painful experiences dealing with depression, anxiety, or fear, and choose not to donate these items, or did so anonymously. For students across the board, assigning the archive allowed them to process their emotions, find community, and better understand the work of historians. In the end, many thanked me for assigning the archive, and the materials they produced proved insightful and profound. Beyond this, students consistently reflected on the links between archives, primary sources, and our understandings of the past.

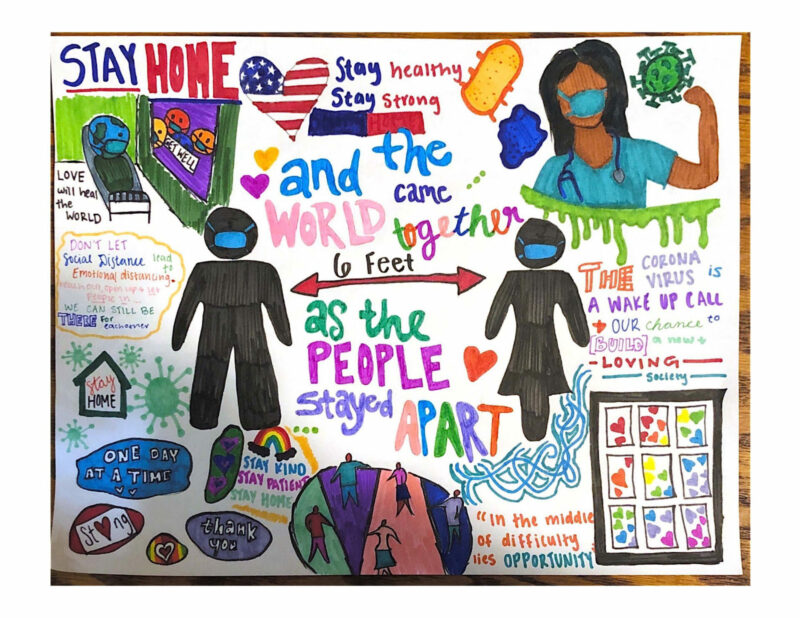

In Cheryl Jiménez Frei’s Latin American history course, a student submitted this piece to JOTPY as a representation of her experiences during the pandemic and her hopes for the future, writing: “I have felt fear, anxiety, sadness and also gratitude for the time I have been with my family and for my health. . . . I [also] started to notice how communities have come together to help each other stay fed and healthy. I have started to appreciate the essential workers who are putting their lives at risk, I even started to notice more hearts in windows, chalk art on the sidewalks, TV commercials, and social media messages finding the good in what is happening during a very dark time.” Sofia Valencia, “Covid as a Collage,” May 18, 2020, JOTPY Archive.

Conclusions and Looking Forward

Incorporating JOTPY proved a rewarding and meaningful experience—for us and the students—and we plan to continue this into the 2020-21 academic year. Personally, it helped us remain connected to our students, empathize with them, and understand the range of authentic, unique experiences they were encountering living through the pandemic. Practically, students drew valuable connections needed to understand the importance of documenting history, even (and perhaps especially) when that history is part of their present.

For the oral histories, despite shared goals of including voices from Asian American, Latinx, Native American, and African American communities, students tended to gravitate towards interviewees who looked like them; in many cases, this meant majority white. As we plan for the fall, one strategy to mitigate this is to require students to interview at least one person outside their own community. We hope this will address archival silences and spur discussions of how actions undertaken by those building, managing, and otherwise influencing the creation and reception of collections wield—though rarely yield—power.

The fall 2020 semester is fraught with disconnections for educators everywhere. Those who teach project-based courses, as we do, might feel on unstable pedagogical ground. Consider bringing the Journal of the Plague Year into your classroom. The archive provides a solid foundation on which to build learning outcomes for your students. It offers opportunities for content creation and curation; interpreting newly-created primary sources; writing for a public, online audience; promoting conversations on archival silences; and taking part in documenting history in real time. Ultimately, it is the hands-on history work that we always aim to provide our students, paradoxically achieved in a remote, socially distanced means compatible with our current world.

~Juilee Decker is an associate professor of history at Rochester Institute of Technology (Rochester, New York) where she directs the Museum Studies/Public History program in the College of Liberal Arts. Her research excavates histories and functions of museums and memorials as part of the process of understanding and critiquing constructions of knowledge and public memory in the U.S.

~Cheryl Jiménez Frei is an assistant professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, where she teaches courses in public history and Latin American history. Her research specializations are in memory and the built environment, Argentina and the Southern Cone, monuments, visual culture, and urban history.