The underbelly of history training: digital methods, ethics, and oral history

19 May 2022 – Sarah Coffman and Elissa Branum

Editors’ Note: This is the third of four essays in a series on labor history, digital humanities, and public history. Authors who wrote essays for this series developed their work as part of a fall 2021 graduate labor history colloquium taught by Dr. Andrew Urban at Rutgers-New Brunswick.

A meme, inspired by the film Toy Story, depicting an exaggerated representation of a graduate student who is anxious about the increasingly digital futures of the humanities discipline and history field.

As early-career graduate students, we think components of social history training (including coursework and faculty mentorship) should expand to include oral history methodologies, digital humanities skills, and community engagement. Increasing support for students to learn digital methods would improve the ethical rigor and dissemination of public-facing research. In October 2021, we spoke with four public and digital historians (Andrew Gomez, Tobias Higbie, Vilja Hulden, and Andy Urban) in a workshop for a Colloquium on Labor History. Informed by that conversation, this blog post discusses how digital humanities can benefit public historians-in-training.

Top to bottom, left to right: Andrew Gomez, Andy Urban, Tobias Higbie, Laura de Moya Guerra, Vilja Hulden, Yazmin Gomez, AJ Boyd, Sarah Coffman, and Elissa Branum.

Research and Teaching

Graduate student training in alternative research methods varies across institutions. Some history departments offer courses on digital methods and oral history collection, summer internship opportunities, or workshops. How can this training better prepare graduate students to use diverse methodologies?

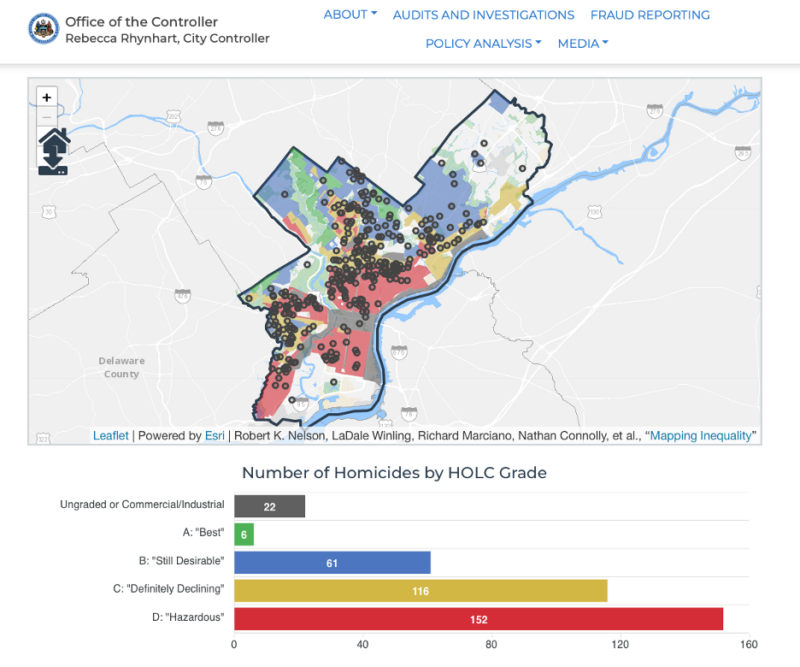

First, coursework opportunities for graduate students could include versatile digital humanities approaches. For example, digital tools help historians sort federal data to uncover systemic inequalities (as in the Mapping Inequality in Philadelphia Initiative). Higbie suggested training should emphasize humility in the face of data—not making totalizing claims, but instead, respecting knowledge’s limits. Quantitative plotting technologies can balance qualitative sources like oral histories, creating fuller recreations of lived experience (see how the Rainbow Heritage Network shares the history of queer historical sites). Learning to combine quantitative and qualitative data can help us balance knowledge’s limits with the imperative to truthfully recount our subjects’ experiences.

A map from the “Mapping Inequality in Philadelphia” initiative.

Second, preparing graduate students to be public historians should include pedagogical training. Most public history work requires collaboration with—and mentorship of—undergraduate students. Using data-sharing tools like maps and digitized public documents in teaching can make historical data less abstract for undergraduate audiences. The humanities can teach undergraduate students tools for grappling with larger concerns about evidence, fake news, and scholarly claims. Urban cautioned that university leadership often capitalizes on the language of collaboration to obscure undergraduate labor in organizing or transcribing research data. Graduate students should learn pedagogical practices aimed at ending cycles of extraction. For example, Gomez has included students in conference presentations. Similarly, Hulden has written recommendation letters to recognize student research labor and mentored students in digital software expertise.

Ethics of digital, public-facing history

Public-facing work that engages with living people, communities, or historic locations has ethical stakes historians should take seriously. Without proper training, oral histories with subjects who have lived through traumatic events can not only be extractive, but also harmful, as we compel individuals to recall intimate details without post-interview support. In what ways should digital methods and oral history training discuss ethics?

Formal ethics guidelines exist in several other social science disciplines and compose foundational courses in undergraduate and graduate education. Qualitative and quantitative research courses in sociology and anthropology, for example, often have built-in discussions of ethics. While historians may face the Institutional Review Board for oral history projects, there are few courses on the ethics of historical research; rather, discussions about methods are removed from discussions about the effects on subjects. For oral histories where interviewees are asked to talk about challenging moments in their lives, training needs to cover how to treat interviewees before, during, and after the interview to 1) create meaningful connections with subjects, 2) do the least harm, and 3) center subject contributions to the overall project.

Community Engagement

In the workshop, Higbie argued community engagement should be the foundation of public history. Labor historians have a history of using digital methods for disseminating research outside the academy. For example, Higbie discussed how H-NET, especially H-Labor, was a radically democratic space where history was conducted equitably across and outside the tenure hierarchy. Created in the 1990s as an email system, H-Labor became a center of transnational communication that included those least connected, including local historians and trade union leaders, to the resources of the academy (for example, sharing sources like this thread on biographies).

A key question is how digital public historians can use technology to widely share the priorities and goals of our subjects. As an example of community engagement, Gomez and Higbie pointed to the Justice for Janitors movement based in the UCLA Labor Center. This was an oral history project where scholars met with labor leaders and considered varying visions of the labor movement. Similarly, website building is important for local histories to gain a larger platform. Gomez and his undergraduate collaborators created the Race in the City of Destiny website to place local Tacoma, Washington, history in the broader context of anti-Asian policy, immigration policy, and urban/housing history.

Gatekeeping

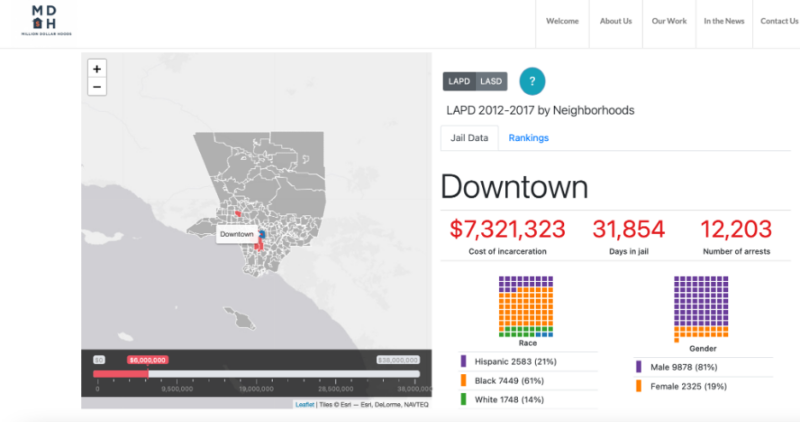

Advanced digital methods gatekeep younger history scholars who are not literate in digital research. We argue senior scholars need to construct more digital methods training opportunities for younger scholars and push major historical organizations to recognize digital public-facing work. Hulden argued graduate and undergraduate training should make digital methods more accessible and less intimidating. This is evident in the panelists’ efforts in their projects to teach undergraduate students the uses and interpretations of digital history. For instance, Higbie discussed the Million Dollar Hoods project, on the human cost of mass incarceration in Los Angeles, as an example of handling human subjects with care on a digital platform. He and other scholars involved undergraduate and graduate students of color in the project, teaching them tools of digital and public history. Similar projects also demonstrate how senior scholars can use public-facing projects to teach undergraduate and graduate students the ethical treatment of living historical subjects.

A map from the “Million Dollar Hoods” project.

Senior scholars must continue to encourage historical associations to recognize digital work as legitimate and equally rigorous historical work. For instance, because digital projects are less respected on the CVs of young scholars, tenured scholars pursue such projects later in their careers. How can creative use of digital platforms promote the growth of the discipline? There is certainly progress in this area, evidenced by increasing numbers of jobs in digital and public history and organizations like the National Council on Public History. We hope to invite more conversation about creative solutions to issues of training, access, and collaboration for graduate students learning digital humanities.

~Sarah Coffman is a first-year Ph.D. student at Rutgers University. Her research concerns white violence against black homeowners and renters who moved into traditionally white neighborhoods in post-WWII Philadelphia.

~Elissa Branum is a Ph.D. student in US History and Latinx History at Rutgers University. Her current research is on race, gender, and labor at evangelical Christian colleges in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.