Playing the public history jukebox (and letting visitors push the buttons)

17 July 2014 – Benjamin Filene

Editor’s Note: In “What I’ve Learned Along the Way: A Public Historian’s Intellectual Odyssey,” outgoing NCPH President Bob Weyeneth issued a call to action to public historians to include the public more fully in our work by “pulling back the curtain” on our interpretive process—how we choose the stories we tell. In this series of posts, we’ve invited several public historians to reflect on projects that do exactly that, assessing their successes and examining the challenges we face when we let the public in through the door usually reserved for staff.

Visitors could listen to tunes from different decades in the Minnesota History Center’s exhibition “Sounds Good to Me: Music in Minnesota, 2000-2007.” Photo credit: Minnesota Historical Society

For a lot of us, the most unsettling part of David Thelen and Roy Rosenzweig’s Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life [1] was the finding that people trust museums (even more than they trust their grandmothers) because museums give them unfiltered history—as if those objects just naturally came in those cases.

In an era when museums were being buffeted by the Culture Wars, we jumped on those findings as good news (they were cited in untold grant applications), but the proper response really should have been “Eek!” If we are doing our jobs, museum visitors would be fascinated to hear why we chose this object instead of the hundreds of others nearly the same in our basements. And they’d appreciate that probably we selected this one because it has a great story associated with it, a story rich with multiple meanings, tensions, debates, and uncertainties. In other words, we’d invite visitors to play along and see where the fun—and the power—of history lies.

Visitors to our sites and museums might feel they have more of a stake in our work if they understand that history is contingent and ever-shifting and that real people—researchers, curators, registrars, media-developers—making dozens of decisions shape how the story gets told. The notion of moving beyond airtight, “just the facts” presentations may seem risky, but I’d like to echo Weyeneth’s call to “lift the veil” and reflect on two relatively simple but perhaps instructive examples that his reflection brought to my mind.

I don’t think that sharing this fundamental insight with the public has to involve elaborate handwringing or footnoting on the wall. For an exhibition on music in Minnesota at the Minnesota History Center, we had working tabletop jukeboxes featuring hot Minnesota songs from different decades. Visitors could push buttons to select their tunes and hear them on the spot. We invited visitors to consider that our selection was not perfect or eternal by setting pencils in front of each jukebox along with 5”-x-7” cards that had a simple invitation: “I Can’t Believe You Left Out…!: Sometimes we got encouraging notes on the cards (“You guys have some Fly songs”), but many people had no problem letting us know that they had their own historical canon of songs: “How about N’Sync or the new stuff?” one young 2000-era student wrote. “I do realize this [the museum] is an oldenday place but come on!” Others made pitches for the 1960s garage bands of their youth or the big bands they loved to dance to in the 1940s at St. Paul’s Prom Ballroom.

At the time I simply saw the cards as ways to encourage reflection and for visitors to blow off steam. I read all the cards, but we didn’t do anything with them. Now, though, I realize that we missed a great opportunity to model historical debate by not posting the cards so that visitors could see each others’ comments. With that simple move, we could have diffused the definition of “expert” in the gallery a bit.

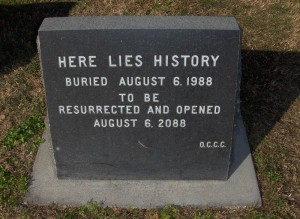

Old City Cemetery time capsule Sacramento, CA. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

We went more in that direction with an exhibition on time capsules that I did at my first museum job, at the Outagamie County (Wisconsin) Historical Society, called Time Capsules: History Goes Underground. Again, we didn’t have to preach about history being a perspectivist postmodern construction. The very form (and ritual) of time capsules did the work for us. As awkwardly shaped vessels containing finite amounts of materials, created by people in particular moments with particular agendas, and salted away to be discovered by the future, time capsules inherently convey the contingency of historical evidence and interpretation.

The exhibit invited people to think about what gets saved and what not and how we in the present piece together stories about the past from fragmentary survivals. In addition to tracing a history of the form, we showcased time capsules created that year by area schoolchildren, which the museum formally buried after the exhibition closed. We also asked people to write “Dear Future” letters in which they shared hopes and fears. Those we posted and compiled in binders for others to see. As well, we invited visitors to engage questions of public memory: “Here is a list of people who were famous a hundred years ago. Who will be remembered a hundred years from now?” (We were in Wisconsin: Brett Favre always won by a landslide.)

I cite these examples because they were low-tech and inexpensive, and they did not involve abandoning historical accuracy, standards, or interpretation. Indeed, turning the historical process inside out need not entail turning it upside down: we can share how history works without giving up on doing history. On the contrary, the invitation to “lift the veil” is a key interpretive move for public history, one that still allows plenty of room for those most central aspects of the history-making process: passion, engagement, and play.

~ Benjamin Filene is Associate Professor and Director of Public History at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

[1] Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998).