Uncovering the hidden paradise of Guantánamo

21 May 2014 – Philip Johnson

Guantanamo Public Memory Project, projects, community history, memory, sense of place, archives, politics

Editor’s Note: This piece continues a series of posts related to the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, a collaboration of public history programs across the country to raise awareness of the long history of the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) and foster dialogue on its future. For an introduction to the series, please see this piece by the Project’s director, Liz Ševčenko.

“My most vivid memories of Guantánamo was everything just being free down there and the closeness of all the people. There was no crime, none whatsoever. It was summer all year round.”

The Guantanamo Public Memory Project online stories collection. Photo Credit: Guantanamo Public Memory Project

Anita Lewis Isom first arrived at Guantánamo Bay forty years before the orange-suited detainees that would make the US base infamous around the world. Her description of an idyllic life at the base seems far removed from the images of leg shackles and barbed wire typically associated with Gitmo in its current function as a “black site,” an extra-legal and extra-territorial space. Images of Gitmo as prison and military base and as island paradise are not, however, mutually exclusive. Indeed, it is in part its isolation that makes Gitmo such an effective black site and its tropical location that has long made it an attractive destination for military families.

Isom’s vision of a hidden paradise at Guantánamo is hardly unique. The Guantánamo Public Memory Project has documented the stories of people who have lived at the base over the past fifty years. The similarities among their accounts of the place are striking.

Aaron Reynolds III arrived at Guantánamo Bay in 1971. He described the base as, “the greatest place in the world for a kid to be raised. No one was going to steal your stuff…. Down there you could wander all you wanted to, ride your bike wherever you wanted to.”

The same themes emerge time and again in these stories. Life on the base was safe and tranquil. An intimate sense of community bound all residents together. The base offered the familiarity of small-town American life with the availability and affordability of luxuries that would have been unimaginable back home: families could own horses, engage housekeepers, and enjoy year-round beach picnics.

This quality of life also attracted Cubans to the base. The Aldama family moved to and lived on the base for decades, between 1961 and 1995. Osvaldo Aldama, who was born on the base, described life there in the following way, “It was a place where you got to know everybody real well. It was a military base but still it had a home, like a home-style type of feeling to it…. You have got mine fields on one side, water on the other, but even though you were confined to that area, you did not feel it. You did not feel like you were trapped.”

Such warmly nostalgic memories are not limited to those who lived at Gitmo during the Cold War. Kenneth Pace was there from 2003 to 2004, but he evokes the 60s when he says, “It was like a heaven on earth, it really was. It was the Mayberry of the world. We knew everybody…. We saw everybody every day. We took care of these people that we saw every day, they took care of us.”

It can be very difficult to reconcile these stories of Gitmo the paradise to the more familiar narratives of Gitmo the black site. Again, however, these narratives are connected. United States military spending has enabled the continued presence of a base at Guantánamo Bay since before the Cuban Revolution, and the various 20th- and 21st-century military campaigns, from the Cold War to the War on Terror, have justified infusions of capital into Gitmo, enabling the lifestyle enjoyed by the base’s resident individuals and families. Such accounts of carefree-if-quotidian life at Gitmo are largely ignored by the media. Advocacy groups seeking to close the prison tend to focus strictly on the experiences of detainees kept beyond the reach of the media and the law. Even those who support the base’s continued use as a black site are mostly concerned with its importance as a bastion against terror.

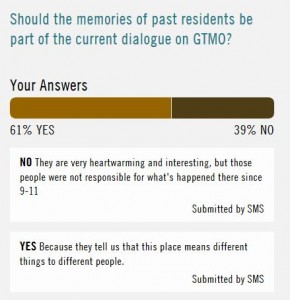

Sample responses to University of West Florida students’ question. Photo Credit: Guantanamo Public Memory Project

Students from the University of West Florida Public History Program gathered more than one hundred oral histories (including those excerpted above) from former Gitmo residents for our project. Having heard so much about the oft-overlooked paradise, these students then threw open the matter of integrating such experiences by posing an open question to the project: “Should the memories of past residents be part of the current dialogue on GTMO?”

Responses to this question have varied tremendously. One respondent declared Gitmo to be “a place of hope for all nations.” Another called the base’s recent history a “travesty that tainted the name of Guantánamo Bay.” A number of former Gitmo residents that visited our traveling exhibit responded to the question by emphasizing that Gitmo is “much more than just a prison.”

This apparent tension between past memory and contentious current dialogue, between the paradise and the black site, misses an important point. As the quote from Kenneth Pace shows, Gitmo did not cease to be a paradise as it became a black site. Equally, the earliest foundations of the black site can be traced far back into the rosy past.

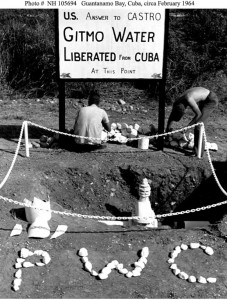

Sign erected on 18 February 1964 proclaims Gitmo’s liberation from the Cuban Government water supply system. Credit: Collection of the Naval Historical Center

The 1960s wasn’t just a time of good neighbors and endless summers at Gitmo. This was also the time in which the ‘Cactus Curtain’ was planted around the base and when the base’s Cuban water supply was cut off. The paradise was being insulated against the adjacent Communist threat, but it was also becoming more isolated, secretive, and remote. The base quickly transformed from a naval base of declining strategic value into a vital symbol of American power. The cost of maintaining the base skyrocketed (the base required its own water conversion plant), even as the cost of living in the paradise was kept artificially low. These were the foundations upon which the black site would later be built.

Without the memories of former residents, we would have little knowledge of the pride and patriotism that came from severing connections with Cuba or of the sense of the paradise’s fragility as the base was evacuated during the Cuban Missile Crisis. We’d have a far dimmer sense of the remoteness of the base–as perceived both by people living there and by people who would like to but will probably never be able to return.

We need to look beyond any perceived barriers between past and present, paradise and black site, warm memories and fierce debates. Only by doing so will we begin to understand how all of these can comfortably coexist within the compact 45 square miles of Gitmo.

As one former Gitmo resident said, in response to the above question, “It would be beyond irresponsible not to have ‘us.’ No one knows the base better, no one knows ‘the other side’ better… Don’t make the mistake!”

~ Philip Luke Johnson is a researcher at New York University and editor for the Guantánamo Public Memory Project. He tweets at @phillegitimate.

I really like the clear and uncompromising way this post sets out what I understand to be the core goal of public history work: to listen carefully to a range of voices and bring them together in the same frame without sacrificing the intellectual and moral clarity that lets us ask good questions about what we’re seeing and hearing. Nicely done.

We were stationed there from 1983-1986. The climate is wonderful. Life was relaxed. There were outdoor movies. Our oldest son was born there. We had the best babysitter who was active on many on-base committees. On the weekend at the commissary I was greeted with, “oh, you’re Garry’s mom”. I would run into a patient on the weekend and they would be on my schedule the next week. Life was great.

Family and I were stationed there 1976-79, lord it and the people you met….